To cite this article

Ressler, W. H. (2012). When “Play for Pink” became playing for each other: Team cohesion as a goal of socially responsible strategic communication. Case Studies in Strategic Communication, 1, article 4. Available online: http://cssc.uscannenberg.org/cases/v1/v1art4

Access the PDF version of this article

When “Play for Pink” Became Playing for Each Other:

Team Cohesion as a Goal of Socially Responsible Strategic Communication

William Harris Ressler

Ithaca College

Abstract

Members of a sports team are often called on to participate in strategic communication activities that are intended to demonstrate social responsibility while enhancing the reputations of their team and their sport. Surprisingly, however, evaluations of outcomes focus almost exclusively on benefits to stakeholders other than the team members. One potential yet essential goal of socially responsible strategic communication activities can be to increase feelings of group cohesion among team members, which in turn can influence individual members’ feelings of well-being, identification with the team, motivation, and ultimately perhaps their athletic performance. This case study examines how members of a women’s intercollegiate athletic team planned, promoted, and performed a fundraiser benefiting local women with breast cancer. Evaluation results suggested that their activities increased their feelings of cohesion with teammates and connection to their college. Interviews with team members suggested that they felt they received the greatest benefit when they had control over the process, opportunities to collaborate within and outside the team, and a personal and local connection to the cause.

Keywords: athletes; breast cancer; cause promotion; intercollegiate athletics; internal marketing; social cohesion; strategic communication; strategic philanthropy; NCAA Division III

Overview

Both internal and external goals drive strategic communication activities. One set of intentional strategic communication goals—strengthening the motivation, commitment, organizational identification, and ultimately

performance of internal stakeholders (e.g., employees)—is reflected in the large and growing interest in internal marketing (Bell, Menguc, & Stefani, 2004; Smith, 2011; Tortosa, Moliner, & Sánchez, 2009; Uslay, Morgan, & Sheth, 2009; Wieseke, Ahearne, Lam, & van Dick, 2009). Involving organization members in philanthropic or voluntary activities, often referred to as strategic philanthropy, has been identified explicitly as a potential internal marketing strategy, with the goal of building stronger connections among organization members and deeper identification with the organization (Bennett & Barkensjo, 2005; Bhattacharya, Rao, & Glynn, 1995; Dutton, Roberts, & Bednar, 2010; Lee, Lancendorfer, & Reck, 2012; Logsdon, Reiner, & Burke, 1990; Maignan & Ferrell, 2001; Saiia, Carroll, & Buchholtz, 2003; Sprinkle & Maines, 2010; Welch & Jackson, 2007; Wilson, 2000). Stronger connections within a group can offer psychosocial benefits to its individual members (Tajfel, 1981; Tajfel & Turner, 1986), and stronger cohesiveness among the members of an organization has been shown to improve the work-related attitudes and behaviors of those individuals (Bell et al., 2004; Bhattacharya, Sen, & Korschun, 2008; Smith, 2011), as well as to strengthen the organization’s performance overall (Freeman, 1994; Freeman, Wicks, & Parmar, 2004). Hence, strengthening group cohesion is a fundamental strategic communication goal to be attained through internal communication activities that accompany an organization’s philanthropic activities.

Background

In the summer of 2009, the coach of a women’s varsity team from a medium-sized, liberal arts college in the Northeast expressed her interest in using her team’s October tournament to promote breast cancer research, education, and support. The coach explained that her primary goal was to inculcate feelings of cohesion among her team members. These feelings are typically expressed through sharing common goals, taking collective responsibility for outcomes, valuing group membership, using “we” more than “I” in discussing their roles, and building a culture of teamwork and mutual support. Involving her team members in socially responsible strategic communication activities would be the means to these internally driven ends.

In past years, the coach had employed various strategies for enhancing social cohesion among team members, including team dinners, movies, and indoor rock climbing. Strengthening social cohesion, she believed, improves athletic performance: “I really believe that when they come together like that, they become stronger, they rely on each other more, they trust each other more, and that’s what we try to accomplish out there when they’re competing. And so you’ve got this wonderful cause, and when they have passion for it and they’re doing it together it just makes sense it would transfer over when they’re competing.” The coach added that when her team members participate together in socially responsible strategic communication activities, “They’re going to feel the accomplishment, and the more they can do off the court together, the more it will help them on the court.” Moreover, she observed, social responsibility provides a broader perspective, beyond athletic successes and failures, and can relieve some of the stress of competing by reducing the impact of failure. “When they recognize it’s bigger than them, it gives them a chance to bond and pull together, and not just for a win or loss, and it just takes pressure off them during the competition… [and] in preparations for the competition.”

The coach’s instincts are supported empirically. College athletes seem to enjoy psychosocial benefit from participating in socially responsible communication activities (Benson, 2006). Sports management studies have suggested that increased cohesion can improve team performance (Carron, Bray, & Eys, 2002; Carron, Coleman, & Wheeler, 2002; Carron & Spink, 1997; Hodges & Carron, 1992; Kozub & McDonnell, 2000; Spink, 1990; Voight & Callaghan, 2002). Trust seems to mediate the effects of internal marketing activities on group cohesion (Back, Lee, & Abbott, 2011; Bell et al., 2004; Smith, 2011; Wilson, 2000). Taken together, the results of studies like these reinforce the cardinality of building group cohesion as a strategic communication goal.

What has been investigated less thoroughly is the connection between athletes’ participation in socially responsible strategic communication activities and team cohesion. Even in the broader organizational context, researchers have pointed out the need for more research to measure specific benefits to internal stakeholders of externally focused philanthropic activities, benefits that include increased employee motivation, organizational identification, and social cohesion; researchers have even suggested that studies should include a before-and-after design with a control group of comparable stakeholders who did not participate in philanthropic activities (Bhattacharya et al., 2008; Sprinkle & Maines, 2010). The current case study adopts this evaluation design in addressing this understudied strategic communication-group cohesion link.

In the process, two additional, related goals of the strategic communication activities are considered: (1) feeling that one’s group is positively valued, based in part on perceived reactions of external stakeholders; and (2) identification with the broader organization. For college athletes, two dominant social identities stand out—being a member of a specific team and being an athlete at a specific college—and the above two goals correspond to each identity. Feelings of cohesion are related to the social identities of the group members, and therefore having a more valued group identity can be associated with feelings of group cohesion.

Belonging to a particular team clearly contributes to an athlete’s social identity. The coach expressed a desire for the team’s philanthropic activities to help the athletes feel better about the team and their roles on it, an outcome that she felt would help to enhance team cohesion. The coach had indicated that this particular sport was not one of the showcase college sports and that it seemed, moreover, to be even less popular on campus than in past years. Engaging in socially responsible communication activities could help players feel even better about the team and thus about themselves by raising the players’ perceived value of their team. This would make belonging to the team more valued and would thus complement increases in team cohesion.

Strategic communication often aims to improve morale and organizational commitment among internal stakeholders by means of its perceived impact on external audiences. DDB’s “We try harder” campaign for Avis is one of the better known advertising campaigns that sought to improve the company’s image among customers and consequently—perhaps primarily—the identification of employees with the company’s mission (Blakeman, 2007). It thus served both a marketing communication function and an organizational communication function. When those communication activities include philanthropy or volunteering in the community, members of the organization can come to believe that doing good makes their organization (and by extension, themselves) more positively valued in the eyes of external audiences, and thus those individuals can feel better about themselves because of the elevated status of their group. These benefits appear to be moderated by enhanced group cohesion, a process that has been referred to as a “relationship-mediated approach to internal marketing” (Ballantyne, 2003). This, then, is an additional and complementary strategic communication goal: improving the perceived value of an organization by doing good, for the psychosocial benefit of the organization’s members, including enhanced self-esteem, improved workplace morale and productivity, strengthened organizational identification, and greater social cohesion (Back et al., 2011; Bhattacharya et al., 1995; Bhattacharya et al., 2008; Burke & Logsdon, 1996; Dutton et al., 2010; Dutton, Dukerich, & Harquail, 1994).

An additional component of college athletes’ social identities is being a student at their particular institution, which can be associated with feelings of cohesion on campus, beyond their specific sports team. Using socially responsible strategic communication activities to build cohesion was articulated not only by the coach but by members of the college’s athletic department as well. College athletic programs at NCAA Division III institutions, such as this one, have been accused in the past decade of being divisive. Some critics have asserted that competition undermines feelings of cohesion among different stakeholder groups, athletes and non-athletes, throughout the college. Disunity among various members of the broader campus community could be reflected in diminished feelings of attachment to the institution or strained relations between student athletes and non-athletes. This could be related to athletes’ sense of being valued on campus, noted above—in this case not as members of a specific team, but as athletes. Hence, members of the athletic department were interested in knowing the extent to which socially responsible strategic communication activities might affect athletes’ feelings toward the college as a whole, a broader expression of cohesion reminiscent of suggestions that internal marketing activities are designed to create stronger feelings of cohesion not only within work teams but also across departments and even between hierarchical levels. The philanthropic actions of a team within a larger organization can help to create an organizational culture of giving; in this case, that would suggest a link between philanthropic, community related activities of student athletes and identification with the college.

Research

Although measuring success in athletic competition was beyond the scope of the current case, an evaluation of the breast cancer promotion was designed to assess the effects of the strategic communication activities on players’ subjective feelings of group cohesion. The evaluation included a survey questionnaire, which used an established and previously validated measure of group cohesion (Carron, Widmeyer, & Brawley, 1985). The questionnaire also included measures of (1) feeling influential—and thus valued—within the campus community and (2) identification with the institution. Following the suggestions of Sprinkle and Maines (2010), the survey was conducted before the team members began their communication activities and after they completed them; survey participants included a control group of members of fall-season women’s sports teams that were not involved in any socially responsible communication activities. Interviews with the coach and players and observation of team meetings aided interpretation of the survey results by providing players’ subjective perceptions of the promotion as it affected them, as individuals and as a team. In addition, the coach and team members invited the author, a strategic communication professor, to participate in team meetings, to offer advice, and to observe the process as the players planned and carried out their strategic communication activities.

Strategy

In September 2009, the coach presented the idea of a campaign and fundraiser to the players. Originally the coach had thought to work with a national organization that organizes breast cancer fundraisers for high school and college teams; the teams then send all money collected back to the organization. After considering her reasons for holding the fundraiser, however, the coach began to consider that a more suitable strategy might be to let the players decide on the goals and processes of the promotion. This intuition has support in the internal marketing literature. Beneficial effects to organization members, including effects on group cohesion, are enhanced when members are given the opportunity to plan and execute philanthropic and volunteer activities themselves (Bennett & Barkensjo, 2005; Liu, Liston-Heyes, & Ko, 2010; Mullen, 1997; Peloza, Hudson, & Hassay, 2009) and internal communication benefits are stronger when the distribution of responsibilities is perceived to be fair (Kim, 2005). Taking responsibility for planning allows organization members to choose a beneficiary that would be a better fit to them, individually and collectively. Thus, although the overall cause was already determined—breast cancer, a good fit for a women’s team competing in the month of October—giving the athletes a chance to pick the specific breast cancer organization allowed them to choose a local organization, potentially a better subjective fit for the athletes, who might have felt their primary responsibilities should be to the local community.

Execution

The team members indeed rejected the idea of letting a national organization run their fundraiser and chose to decide themselves how to raise money and for whom, as well as how to promote the event and deliver breast cancer messages. They collectively decided on a beneficiary, a local cancer resource center that aids people dealing with breast cancer.

Planning the communication activities became an opportunity to build team cohesion. Players used downtime during team bus travel to write down ideas for the campaign and to exchange ideas for promotional poster designs. They used team meetings before or after practices to decide on the name of the promotion—“Play for Pink”—and to divide up responsibilities. They pooled their ideas to identify possible donors from the local business community, and businesses on the list were divided equally among small groups of players. Together, players considered different ways to raise money. They designed and ordered pink silicon bracelets with “Play for Pink” stamped on them, which would be given to donors, before and during the tournament, and they held a silent auction of team-autographed pink-and-white balls.

Players reserved tables in the student union the week before the tournament, and they organized a staffing rotation to publicize the tournament, to solicit student donations and pass out pink bracelets, and to distribute brochures about breast cancer risks, prevention, and detection. They advertised the tournament through posters, which players designed and then posted on campus and in the downtown commercial district (see Appendix A). Players took advantage of public relations opportunities by writing articles that appeared in print and online campus media (see Appendix B). These included an op-ed about the team’s efforts that also included information about breast cancer, written by one of the players and published the week of the tournament in the print and online editions of the college newspaper (see Appendix C).

Consistent with the broader, college-wide goal of creating social cohesion outside the team, members of the team worked with other student groups on campus to carry out the strategic communication activities. For example, promoting the tournament was facilitated by a student organization that consisted of undergraduates majoring in strategic communication. These strategic communication students helped turn the players’ ideas for posters into actual camera-ready designs and assisted in distributing them. They contacted the editors of the college newspaper and helped to secure agreement for the student-written piece to appear as an op-ed and then helped proofread and edit the article prior to submission. These students also helped post brief tournament announcements on the college’s main online forum.

Team members also worked with the athletic department’s office of information, providing details of the promotion. As a result, brief articles appeared on the splash page of the college’s main athletics website (see Appendix D).

At the tournament, when the team members were busy competing, a graduate student and a faculty member volunteered to sit at a table by the entrance. A staff member from the local cancer center was also present to answer questions about breast cancer risks, detection, and treatment. Informational brochures provided by the cancer center were available throughout the tournament. Volunteers handed out the brochures, gave the pink bracelets to donors, and collected bids for the silent auction (see Appendix E).

In addition, players spread information about the promotion to other teams through word of mouth and social media. As a result, many of the teams competing in the tournament arrived wearing either pink warm-up tops or pink game jerseys. Some also wore pink hair ribbons.

Not all efforts to organize the promotion were successful. One idea players had was to solicit sponsorships or donations from local businesses to offset the cost of the bracelets and even, perhaps, to pay for some article of clothing that players could wear at the tournament and sell to players from other teams. Because the planning for the fundraiser began late, not enough time was left for properly soliciting potential donors or for ordering articles of clothing. Moreover, many of the players said that they felt uncomfortable approaching business owners. In the end, the cost of the bracelets came from the money raised. Nevertheless, enough money was raised to offset the cost of the bracelets and still make a generous donation to the local cancer center.

Evaluation

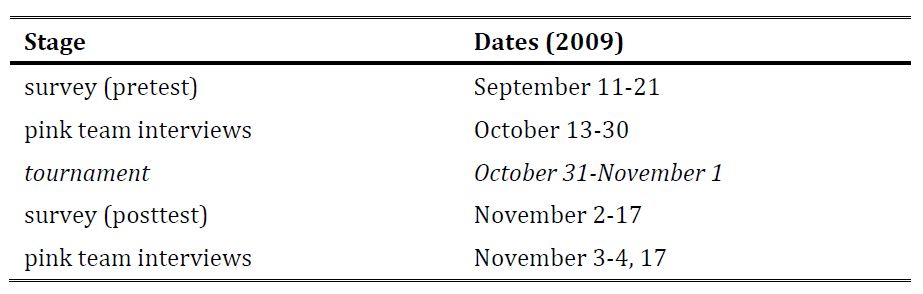

Consistent with suggestions for measuring internal stakeholder benefits that result from strategic communication—specifically internal marketing—evaluation was carried out before and after the team members’ communication activities. It included a within-subject, pretest-posttest survey with control. In addition, the coach and members of the team, from this point forward referred to as “the pink team,” were interviewed. The evaluation was supported by a research grant from the NCAA. Table 1 presents the evaluation timeline.

Table 1. Overall timeline of the evaluation.Quantitative data

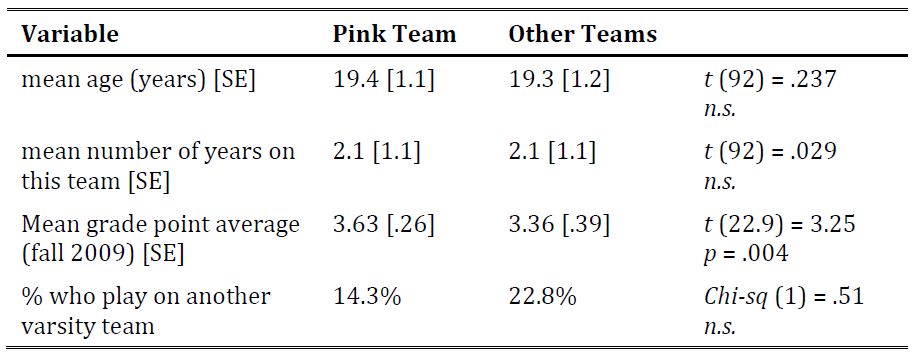

All survey participants were varsity athletes, ages 18 through 22, undergraduate students at an NCAA Division III college in the Northeast. They included the members of the pink team and the members of three of the four other women’s varsity, fall-season teams. The survey took less than five minutes to complete. Questionnaires were completed at a team practice or meeting. The short, single-page questionnaire included demographic items and attitudinal measures. Analyses included players who completed both pre- and posttest questionnaires: 11 members of the pink team and 66 members of the three teams that were not participating in this or any other promotion that semester. With respect to age, seniority, and playing other sports, members of the pink team did not differ significantly from the other athletes (see Table 2). The athletes’ grade point averages for the semester in which the promotion took place, however, did differ significantly between the pink team and the others. Competitive success did not differ systematically among the four teams or between the period immediately preceding the pretest and the period immediately preceding the posttest.

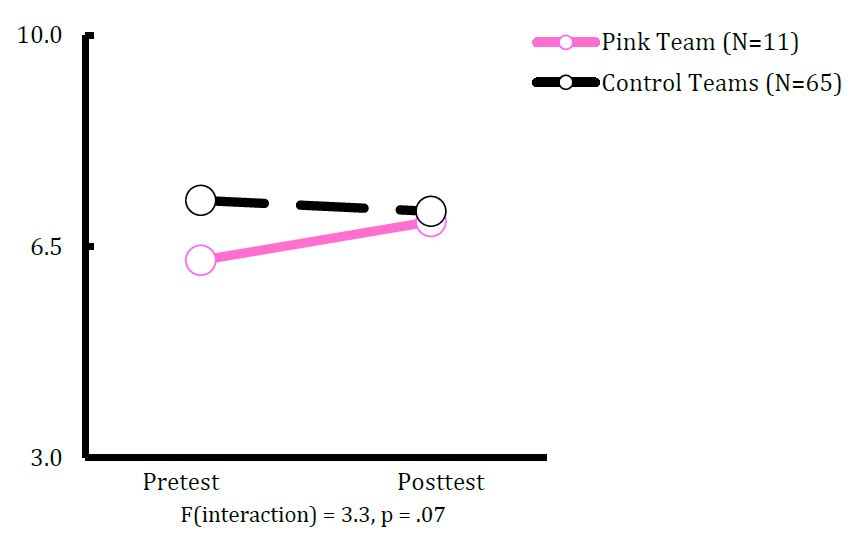

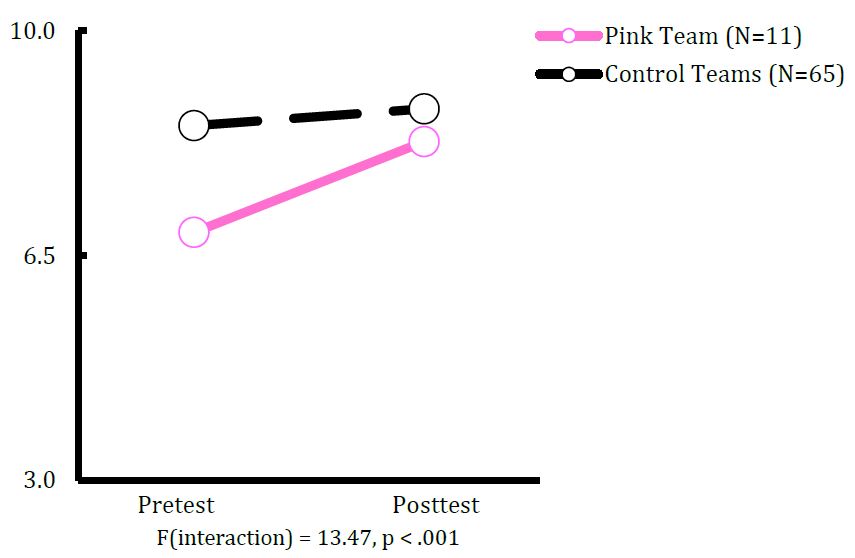

Table 2. Comparisons of the pink team with the other in-season, women’s varsity teams (control).Items used to measure group cohesion came from the Group Environment Questionnaire (GEQ), a reliable (α = .85), validated instrument (Carron et al., 1985). Two items from the “Individual attractions to the group-social” sub-scale were chosen on face validity: (a) “Some of my best friends are on this team,” and (b) “For me, this team is one of the most important social groups to which I belong.” The two items had a reliability of α = .74. From pre- to posttest, the pink team’s mean score rose from 6.86 (SE = .51); to 8.27 (SE = .33), a significant increase [t paired samples(10) = 3.27, p < .01]. Given the narrow range of scores—90% of all the athletes’ scores fell between 6 and 10—this increase of 1.41 points was especially salient. It closed the gap between the pink team and the others; a repeated measures analysis of variance of showed that this interaction between time and team was significant [F(1, 74) = 13.47 (p < .001)] (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Social cohesion of the pink team and control team athletes, before and after the pink team’s strategic communication activities.

Figure 1. Social cohesion of the pink team and control team athletes, before and after the pink team’s strategic communication activities.

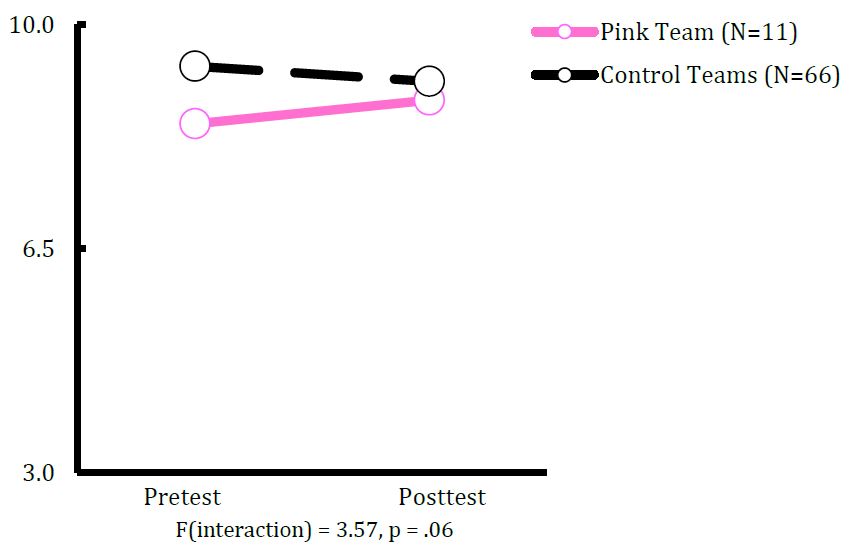

A single item, “I feel that, as an athlete, I can make a difference on campus,” was used to measure players’ perceptions of the extent to which other students valued their team and athletes, in general. The pink team’s mean score increased at posttest, relative to the other female athletes; a repeated measures analysis of variance of this interaction was significant, F = 3.3 (p = .07) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Perceived influence on campus of the pink team and control team athletes, before and after the pink team’s strategic communication activities.To measure wider feelings of social cohesion, one item, “I am proud to tell other people that I go to [this college],” was chosen from the Organizational Identification Scale (Mael, 1988). The pink team’s mean score increased following the promotion, relative to the other female athletes. A repeated measures analysis of variance of the interaction was significant, F = 3.57 (p = .06) (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Institutional identification of the pink team and control team athletes, before and after the pink team’s strategic communication activities.Qualitative data

To help in interpreting the survey results, an undergraduate researcher interviewed the coach and six players before the tournament—two individually and four in pairs—and four players, all individually, two days after the tournament. The author conducted a focus group with nine players and interviewed the coach, two weeks after the tournament.

Players’ comments during the weeks preceding the tournament suggested that they sensed that organizing and carrying out the range of communication activities would accompany increased team cohesion: “I think in a way it will bring us together, I think it will make us feel good as a team.” Players connected increased feelings of cohesion to the actual work they were doing together, including tabling, designing or hanging posters, or soliciting donations. As an example, after beginning collective activities, another player commented, “I think it will help us feel like we’ve all accomplished something, that we’ve done something together.” A third player said, “I’m not sure about how, exactly, it will unify us… maybe just in our heads, it will make us feel good about what we did.” Most of the interviewees used “we” and “us” to describe the effects of the promotion on themselves.

Not all players who were interviewed expressed feelings of increased social cohesion as a result of their collective activities. Indeed, one player, in contrast to other players interviewed, used “me” much more than “we” in her comments. Nonetheless, even though she doubted whether the team’s efforts would affect team cohesion, she expressed pride in the group’s achievement and, more tellingly, an emotional satisfaction in their socially responsible activities: “It makes me feel good about what we’re doing, but it doesn’t directly change my feelings about the team as a whole.” This is consistent with studies, noted above, that have suggested that one important strategic benefit of internal marketing paired with philanthropic activity is strengthening the subjective well-being of organization members. Perhaps athletes can feel better personally, independent of effects on group cohesion, or perhaps positive identity can be a result of unacknowledged changes in cohesion.

Moreover, even when a player expressed doubts that the team’s communication activities would increase team cohesion, the choice of a local beneficiary was singled out for special praise. Players indicated that they felt that the local cancer center was indeed a good fit for them and made their efforts more worthwhile, more personally rewarding, and perhaps of greater benefit to group cohesion. As one player noted before the tournament, “I think it will make us feel good as a team, when we see the outcome, see the donations go to the [local] cancer center.”

It also seemed that it was the location of the beneficiary more than the cause itself that mattered to players. While most players interviewed said that breast cancer was a good fit for the team, one player noted that, “The actual cause, not that it doesn’t matter, but I would feel good about it no matter what, if we were to raise money to help anything” and “we would have done the same amount of work.” One player, echoing the words of several others, said, “It’s a really good cause, but it’s really popular right now, so a lot of places are doing it already, so if we could have a different organization to give money to, that would be nice, too.”

Players also validated the coach’s decision to allow them control over the communication activities. In talking about the lessons learned, for example, players connected feelings of control to subsequent feelings of cohesion. One player said, “Coaches being on you, it’s different than one of your teammates … relying on you.”

Although the coach tried to encourage all players to participate equally in planning and carrying out the communication activities, and the players themselves clearly expected equal efforts from their peers, the coach and players indicated that some players took more responsibility than others. For example, in a representative (and candid) observation, one player commented, “Everyone helped out a little bit, but… It just seems like it wasn’t necessarily an even distribution… I don’t think I did that much.” This could have led to a degree of resentment among the team members. Because the literature on collective philanthropic activity and cohesion has underscored the mediating role of perceived fairness in the distribution of responsibilities, as noted above, differences in players’ perceived efforts could have undermined the overall goal of increasing team cohesion, explaining the tendency for a minority of team members to question the efficacy of the team’s activities in building cohesion.

Players mentioned their feelings of identification with the college and their potential influence on other students when reflecting on the effects of the breast cancer promotion. In particular, students discussed their perceptions of how members of the campus community viewed them and their team. Some expressed the hope that the breast cancer promotion would change theretofore negative perceptions: “I hope it changes their opinions and [non-athletes] realize that … we actually do care.” Others seemed more certain: “This will help put us in a different light, to show that we do other things.” One player, in particular, summed up the various aspirations that team members seemed to feel regarding the effect of this promotion on perceptions of them on campus: “I think they’ll definitely look at it as, ‘Oh, the [pink] team’s supporting this, that’s pretty cool,’ like maybe they’ve never thought that athletes have time or that athletes care about stuff like this . . . Maybe it’ll make them more supportive of us, just ‘cause they see what we’re doing and it makes them want to be supportive of us.” These perceptions echo results from studies of the benefits of corporate social responsibility (CSR) for internal stakeholders, in which CSR activity leads internal stakeholders to believe that external audiences value the organization more positively, which can increase the positive valence of the internal stakeholders’ social identity, which in turn can enhance their psychosocial well-being (Aguilera, Rupp, Williams, & Ganapathi, 2007; Bhattacharya, Korschun, & Sen, 2009; Maignan & Ferrell, 2004). The strategic communication activities described in this case, however, do not represent CSR, per se (see, e.g. Pohle & Hittner, 2008). This was, in part, because the effect on external stakeholders’ perceptions of the team were incidental. The coach’s decision to engage her team in the philanthropic activity and accompanying strategic communications was driven by internal communication goals, specifically the need to enhance cohesion among team members.

An additional comment captured a pervasive sense of responsibility expressed by many on the team: “[This is] something we should do and we should have done more in the past.” Many said that having had more time would have allowed them to create even better communications and to engage more external stakeholders, including fans, other students, and local businesses. It can be inferred that this feeling of obligation comes, in part, from the sense that their work in planning and carrying out this socially responsible strategic communication project indeed benefited their intended audiences—including the players themselves.

Analysis and Discussion

Results of the evaluation of “Play for Pink” suggest that socially responsible strategic communication activities have inwardly directed, intentional goals. These goals include increased group cohesion among those who plan and carry out the activities, a strategic communication goal that has implications for inculcating and identifying with a group culture, improving individual motivation and performance, and ultimately, perhaps, enhancing collective success.

Beyond a statistically significant increase in team cohesion, as measured by survey items, players seemed to feel that their communication activities on behalf of the local cancer center would and did help foster team cohesion. The pink team’s reflections on their experiences suggested that the structure of communication activities affects the extent to which athletes derive benefits of stronger team cohesion. Drawing from their introspections leads to a number of recommendations for organizing socially responsible strategic communication.

“Play for Pink” was the coach’s initiative, not the players’; athletes’ participation in socially responsible strategic communication activities is typically not entirely voluntary. Nonetheless, pink team members’ comments suggested that athletes are better served when they are allowed to make choices about goals, strategies, and tactics. This not only allows athletes to feel more invested, by making the promotion personally relevant; it allows them to contribute in ways that better match their personal skill sets, a direction being pursued by more and more corporations looking to encourage employee volunteering in order to enhance feelings of cohesion among employees (Needleman, 2008).

Having opportunities to develop relationships with other stakeholders on campus appeared important to members of the pink team. Team members talked about feeling more connected to non-athletes on campus, and these comments were consistent with survey results. When team members said they wished they had had more time to prepare, this could reflect a desire to have had more opportunities for engaging students, faculty, or staff who do not otherwise interact with the athletic program. Working with these audiences in planning, executing, and evaluating socially responsible strategic communication activities can benefit athletes by strengthening feelings of cohesion beyond their team—i.e., to the institution. This process is analogous to the use of CSR to enhance social cohesion among broader employee groups, horizontally across work team boundaries and vertically up and down organizational hierarchies (Needleman, 2008).

The local dimension of “Play for Pink” was important to players, beyond providing opportunities for broader social cohesion within the campus environment. Immediate and directly observable outcomes are more rewarding, and positive feedback is associated with group cohesion. This is another reason why having a nearby beneficiary may have had a more powerful impact on the pink team’s feelings of cohesion: Helping a local cause offered immediate and tangible reinforcement for these athletes’ efforts. Athletes say that actually doing good is what makes them feel good (Ressler, Itman, & Rodriguez, 2012). Therefore, demonstrating the connection between efforts and outcomes is essential to achieving the internally directed goals of socially responsible strategic communication activities, including enhanced team cohesion.

Cohesion can also come from working together to do something special, something uniquely suited to the group. Some players said they felt connected to the cause, because breast cancer mostly affects women. Some players even suggested, however, that while breast cancer was a worthwhile cause, choosing a less popular cause would have made them feel even better about their socially responsible activities. It appeared that, more than a generic fit between the cause and the organization or the cause and the individual, it was the idea of owning a cause—of having a more personalized fit between the cause and the organization—that could offer the best opportunities for building team cohesion.

Some pink team players pointed out that not all of them contributed equally. Even in perceiving inequalities, however, players tacitly recognized the importance of their perceptions of procedural justice in the apportioning and execution of complementary tasks. For maximum benefit in strengthening feelings of team cohesion, these athletes believed, the efforts put forth in doing good should be equal, or at least perceived to be equitable. Their reactions underscore the influence of perceived procedural fairness on the extent to which group cohesion can result from socially responsible strategic communication activities.

Even though evaluations did not permit making inferences about a connection between team cohesion and competitive success, studies of internal marketing and philanthropic activities and an observation by the pink team’s coach suggest avenues for future study: “I wonder—[player’s name], perfect example—very slow start, injury, very slow comeback, we get to this breast cancer awareness effort, she’s taken a huge role, her play got much better. I don’t know. Is that just because she got healthier or did she feel like she had a bigger part in this group?” Injuries can make athletes feel marginalized; perhaps socially responsible strategic communication can remedy those feelings. If sports teams can be a model for workplace teams (Katz & Koenig, 2001), then participating in socially responsible internal communication activities could compensate for feelings of alienation in the workplace and among members of workplace teams.

Although the case study did not evaluate changes in non-athletes’ actual perceptions of the pink team, the players’ expectations that those perceptions would change as a result of “Play for Pink” suggest that future evaluations of athletes’ involvement in socially responsible strategic communication will look more systematically at the interaction between external perceptions of the team and feelings of cohesion within the team. It would certainly be interesting to examine actual changes in non-athletes’ attitudes following athletes’ socially responsible strategic communication activities, and even to measure additional outcomes (higher attendance, success in competition) that would make future case studies an exploration of broader CSR activities.

Many of the elements of organizing a philanthropic activity that seem to have contributed to group cohesion within the “Play for Pink” team have also been identified as characteristics of effective leadership development activities among college students: commitment, collaboration, an equitable division of labor, shared purpose, and competence in planning and carrying out the activity, as well as building bridges across departments and disciplines and among different campus community members and including time for reflection (Astin & Astin, 2000; Moorman & Arellano-Unruh, 2002; Stanton, Giles, & Cruz, 1999). Indeed, understanding the potential contribution of philanthropic activity to college athletes’ leadership development may have motivated the NCAA’s interest in supporting the evaluation of this philanthropic project.

Building solidarity through challenge and success, sharing the lessons of proper preparation and execution, and not merely being together and doing together but succeeding together are hallmarks not only of socially responsible strategic communication activities but also of the very essence of competing in a team sport—or succeeding on a workplace team. “Play for Pink” reinforced the importance of considering the needs of and benefits to internal stakeholders when planning a communication campaign, in particular the desirability of making group cohesiveness a primary strategic communication goal. Indirectly, perhaps, “Play for Pink” also served as a reminder of the integrative nature of strategic communication, a reminder that strategic goals apply to both external and internal audiences, and a reminder to step outside the silos of organizational, corporate, and marketing communications. Ultimately strategic communication is about the possibilities that come from building connections among the many elements of the complex and interdependent systems in which organizations function, and sports teams and their members provide fertile ground for exploring those possibilities.

Discussion Questions and Activities

- To what extent can lessons learned from this case study be applied to members of other types of organizations?

- What potential benefits, other than group cohesion, should be used to evaluate the impact on the members of an organization who carry out socially responsible strategic communication?

- Some pink team members noted that their sport, in the words of one player, is “not that popular a sport, sadly enough.” How might a cause promotion be organized and assessed in order to improve the team members’ perceptions of how other students on campus regard them?

- The pink team coach believed that strengthening team members’ feelings of cohesion would help them to play better in competitions. Choose an organization, such as a sports team, a student service club, or a business, and consider its goals. Now design a means for evaluating whether changes in cohesion among the members of that organization actually contributed to achieving those goals.

- It has been suggested that strategic communication can be more effective when all stakeholders, including the people promoting the cause, are actively engaged, from planning to execution. Design a student-led campaign to promote using a designated driver that takes into account the perspectives of all stakeholders, and explain how to engage each set of stakeholders in ways that will make the campaign more effective.

References

Aguilera, R. V., Rupp, D. E., Williams, C. A., & Ganapathi, J. (2007). Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility: A multilevel theory of social change in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 32, 836–863.

Astin, A. W., & Astin, H. S. (2000). Leadership reconsidered: Engaging higher education in social change. Battle Creek, MI: W.K. Kellogg Foundation.

Back, K-J., Lee, C-K., & Abbott, J. (2011). Internal relationship marketing: Korean casino employees’ job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 52(2), 111-124.

Ballantyne, D. (2003). A relationship-mediated theory of internal marketing. European Journal of Marketing, 37, 1242 – 1260.

Bell, S.J., Menguc B., & Stefani S.L. (2004). When customers disappoint: A model of relational internal marketing and customer complaints. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 32(2): 112–126.

Bennett, R., & Barkensjo, A. (2005). Internal marketing, negative experiences, and volunteers’ commitment to providing high-quality services in a UK helping and caring charitable organization. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 16, 251-274.

Benson, M. (February 13, 2006). The takeaway on giving back. The NCAA News, A1.

Bhattacharya, C. B., Korschun, D., & Sen, S. (2009). Strengthening stakeholder–company relationships through mutually beneficial corporate social responsibility initiatives. Journal of Business Ethics, 85, 257–272.

Bhattacharya, C. B., Rao, H., & Glynn, M. A. (1995). Understanding the bond of identification: An investigation of its correlates among art museum members. Journal of Marketing, 59, 46-57.

Bhattacharya, C. B., Sen, S., & Korschun, D. (2008). Using corporate social responsibility to win the war for talent. MIT Sloan Management Review, 49(2), 37–44.

Blakeman, R. (2007). Integrated marketing communication: Creative strategy from idea to implementation. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Carron, A. V., Bray, S. R., & Eys, M. A. (2002). Team cohesion and team success in sport. Journal of Sports Sciences, 20, 119-126.

Carron, A. V., Coleman, M. M., & Wheeler, J. (2002). Cohesion and performance in sport: A meta analysis. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 24, 168-188.

Carron, A. V., & Spink, K. S. (1997). Team building and cohesiveness in the sport and exercise setting: Use of indirect interventions. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 9, 61-72.

Carron, A. V., Widmeyer, W. N., & Brawley, L. R. (1985). The development of an instrument to assess cohesion in sport teams: The Group Environment Questionnaire. Journal of Sport Psychology, 7, 244-266.

Dutton, J. E., Dukerich, J. M., & Harquail, C. V. (1994). Organizational images and member identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39, 239-63.

Dutton, J. E., Roberts, L. M., & Bednar, J. (2010). Pathways for positive identity construction at work: Four types of positive identity and the building of social resources. Academy of Management Review, 35, 265–293.

Freeman, R. E. (1994). The politics of stakeholder theory. Business Ethics Quarterly, 4, 409-421.

Freeman, R. E., Wicks, A. C., & Parmar, B. (2004). Stakeholder theory and “The corporate objective revisited.” Organization Science, 15, 364-369.

Hodges, L., & Carron, A. V. (1992). Collective efficacy and group performance. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 23, 48-59.

Katz, N., & Koenig, G. (2001). Sports teams as a model for workplace teams: Lessons and liabilities. The Academy of Management Executive, 15(3), 56-69.

Kim, H.-S. (2005). Organizational structure and internal communication as antecedents of employee-organization relationships in the context of organizational justice: A multilevel analysis. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Maryland, College Park.

Kozub, S. A., & McDonnell, J. F. (2000). Exploring the relationship between cohesion and collective efficacy in rugby teams. Journal of Sport Behavior, 23, 120-129.

Lee, H., Lancendorfer, K. M., & Reck, R. (2012). Perceptual differences in corporate philanthropy motives: A South Korean study. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 17, 33-47.

Liu, G., Liston-Heyes, C., & Ko, W-W. (2010). Employee participation in cause-related marketing strategies: A study of management perceptions from British consumer service industries. Journal of Business Ethics, 92, 195-210.

Logsdon, J. M., Reiner, M., & Burke, L. (1990). Corporate philanthropy: Strategic responses to the firm’s stakeholders. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 19, 93-109.

Mael, F. (1988). Organizational identification: Construct redefinition and a field application with organizational alumni. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Wayne State University, Detroit.

Maignan, I., & Ferrell, O. C. (2001). Corporate citizenship as a marketing instrument. European Journal of Marketing, 35, 457–484.

Maignan, I., & Ferrell, O. C. (2004). Corporate social responsibility and marketing: An integrative framework. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 32, 3-19.

Moorman, M. K., & Arellano-Unruh, N. (2002). Community service-learning projects for undergraduate recreation majors. The Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 73(2), 42-45, 52.

Mullen, J. (1997). Performance-based corporate philanthropy: How “giving smart” can further corporate goals. Public Relations Quarterly, 42, 42-48.

Needleman, S. E. (2008, April 29). The latest office perk: Getting paid to volunteer — more companies subsidize donations of time and talent; bait for millennial generation. The Wall Street Journal Online. Retrieved from http://online.wsj.com/article/SB120940853880850351.html

Peloza, J., Hudson, S., & Hassay, D. N. (2009). The marketing of employee volunteerism. Journal of Business Ethics, 85, 371–386.

Pohle, G., & Hittner, J. (2008). Attaining sustainable growth through corporate social responsibility. Somers, NY: IBM Global Services.

Ressler, W. H., Itman Bocchi, S., & Rodriguez Maria, P. (2012). English- and Spanish-speaking minor league baseball players’ perspectives on community service and the psychosocial benefit of helping children. NINE, 20, 92-116.

Saiia, D. H., Carroll, A. B., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2003). Philanthropy as strategy : When corporate charity “begins at home.” Business Society, 42, 169-201.

Smith, A. (2011). Internal social marketing: lessons from the field of services marketing. In G. Hastings, K. Angus, & C. Bryant (Eds.), The Sage handbook of social marketing (pp.298-316). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Spink, K. S. (1990). Group cohesion and collective efficacy of volleyball teams. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 12, 301-311.

Sprinkle, G. B., & Maines, L. A. (2010). The benefits and costs of corporate social responsibility. Business Horizons, 53, 445-453.

Stanton, T., Giles, D., & Cruz, N. I. (1999). Service-learning: A movement’s pioneers reflect on its origins, practice, and future. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Tajfel, H. (1981). Human groups and social categories. Cambridge: Cambridge University.

Taijfel, H., & Turner, J.C. (1986). Social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In W. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (2nd ed., pp. 33–47). Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

Tortosa, V., Moliner, M. A., & Sánchez, J. (2009). Internal market orientation and its influence on organizational performance. European Journal of Marketing, 43, 1435-1456.

Uslay, C., Morgan, R. E., & Sheth, J. N. (2009). Peter Drucker on marketing: An exploration of five tenets. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 37, 47–60.

Voight, M., & Callaghan, J. (2002). A team building intervention program: Applications and evaluations with two university soccer teams. Journal of Sport Behavior, 24, 420-430.

Welch, M., & Jackson, P. R. (2007). Rethinking internal communication: A stakeholder approach. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 12, 177-198.

Wieseke J., Ahearne M., Lam S.K. & van Dick, R. (2009). The role of leaders in internal marketing. Journal of Marketing, 73, 123-145.

Wilson, L. J. (2000). Building employee and community relationships through volunteerism: A case study. In J. A. Ledingham & S. D. Bruning (Eds.), Public relations as relationship management: A relational approach to the study and practice of public relations (pp. 137-144). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

WILLIAM HARRIS RESSLER, Ph.D., is an assistant professor in the Department of Strategic Communication at Ithaca College. His research focuses on socially responsible strategic communication activities from the perspective of the sports teams and individual athletes who carry them out, looking especially at culture, cultural diversity, and strategic communication among minor league baseball players. Email: wressler[at]Ithaca.edu.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported largely by a CHAMPS/Life Skills Grant from the NCAA.

The author wishes to thank Michael Lindberg for securing the funding for this project, for enabling the quantitative research to be carried out, and for all of his insights in interpreting the results of the evaluation. The author wishes to thank Sebastian Itman Bocchi and Alua Satybaldina for their assistance in collecting and entering the survey data.

The qualitative data analysis was supported, in part, by a James B. Pendleton Faculty Research Grant from the Ithaca College School of Communication. The author wishes to thank Rebecca McCabe for her work arranging and conducting the interviews, Mary Lou Kish, for her work in analyzing the interview data, and Howard Kalman, along with the editor of this journal and two anonymous reviewers, for their very helpful comments on the manuscript.

The author wishes to thank Wenmouth Williams, Jr., for his help in planning the evaluation, interpreting the results, and contributing to earlier versions of the manuscript. The author especially wishes to express his deepest gratitude to the players, coaches, and staff of the athletic teams whose generous sharing of their time, feelings, and insights created this case study.

Portions of this study were presented at the NCAA CHAMPS/Life Skills Continuing Education Conference, February 10, 2010, Tampa, Florida.

Editorial history

Received December 8, 2011

Revised April 18, 2012

Accepted June 5, 2012

Published June 14, 2012

Handled by editor; no conflicts of interest

Appendix A. Student designed posters (identifying information removed).

Appendix B. Announcements on the campus’ main online forum (identifying information removed).

Appendix C. Op-ed, written by a member of the pink team, from the online edition of the college newspaper (identifying information removed).

Team to raise money for local cancer patients

October is full of pink ribbons. Many organizations are raising money for breast cancer this month, including the [SPORTS] team. The team is hosting “Play for Pink” from Oct. 31 to Nov. 1.

We are taking advantage of our final home tournament as an opportunity to give back to our community by raising money for the Cancer Resource Center [LOCATION]. All of the money we raise will benefit local women and their families facing breast cancer. The center truly has a personal touch — they set up a community for people to turn to in a scary time in their lives. The organization is dedicated to individuals’ needs, asking how they can help to ensure that they are providing everyone with the assistance they require. Its motto, “because no one should face cancer alone,” shows its compassion and dedication to the individual, which is why we want to donate the money specifically to the local organization.

Many [SPORTS] teams host events where teams pair up with an organization to raise money for a national organization. However, we wanted to help people here in [CITY]. Because this is new, and because we are not getting help from any national organizations, we have had to design all the aspects of the promotion ourselves. We also came up with ideas for ways in which we would raise the money and educate other students about making healthier choices to reduce the risk of breast cancer.

Graduate Assistant Coach [NAME] is coordinating the players, but each of us is using what we have learned here at the college about strategic communication, event planning and health promotion to design posters, reach out to local businesses and organize game-day events that will benefit students and residents.

We are not doing the work by ourselves. We have received support from the Communication […] Student Association [COLLEGE]. They have been helping us organize our ideas and to learn how to promote an event like this. We also have the support of the athletic department. Many other teams throughout the year devote their time to supporting causes. Now we’re a part of a greater effort at the college.

Working together for this cause has brought us even closer together as a team and as responsible members of the college community. We love that we have the ability to use our sport as a way to raise money to fight this common, destructive disease. While putting the fundraiser together, we were educated about proper diet and lifestyle tips to reduce the risk of getting breast cancer. We are thrilled with the opportunity to raise money for breast cancer because unfortunately most of us have been in some kind of contact with this awful disease.

We will be hosting a table before the tournament. At the tables and at the tournament, there will be brochures to educate young women (and men) about reducing the risk and enhancing the early detection of this devastating disease.

Exercise, good nutrition and maintaining a healthy weight can all reduce the risk of breast cancer. Simple choices, like replacing a couple of fried, fatty snacks each day with a few more fruits and vegetables, taking the stairs instead of the elevator or walking to class instead of driving can add up to a big reduction in the risk of cancer. We have the power to make choices and to make a difference for our own health and, this weekend, for others’ health as well.

So remember to come down to the [NAME] Gymnasium on Saturday or Sunday to support a great cause. And don’t forget to wear pink.

Appendix D. Online announcement on the athletic department’s website (identifying information removed).

Appendix E. Promotion during the Play for Pink tournament (identifying information removed).