To cite this article

Swanson, D. J. (2012). From ‘hour of power’ to ‘days of demise’: Media portrayals of crisis and fractured social order within Robert H. Schuller’s Crystal Cathedral ministry. Case Studies in Strategic Communication, 1, article 8. Available online: http://cssc.uscannenberg.org/cases/v1/v1art8

Access the PDF version of this article

From ‘Hour of Power’ to ‘Days of Demise’:

Media Portrayals of Crisis and Fractured Social Order within Robert H. Schuller’s Crystal Cathedral Ministry

Douglas J. Swanson

California State University, Fullerton

Abstract

The purpose of this case study is to illustrate the importance of organizations in crisis to engage media gatekeepers through different forms of communication. The case study offers an analysis of media coverage from 2010-2012, a period in which financial losses and family squabbling resulted in the dissolution of Robert H. Schuller’s Crystal Cathedral Ministry. Ministry leadership failed to follow accepted principles of crisis communication by not effectively addressing topical issues critical to stakeholders. Additionally, the news content that formed the basis of this analysis illustrates that Crystal Cathedral’s communication efforts suggested a fractured, discordant social order that did not suggest the organization was capable of survival after loss of the edifice with which the ministry was identified. Ultimately, this case study demonstrates that religious groups and other similar organizations to which stakeholders have strong emotional ties must engage in effective crisis communication on topical issues. Organizations must also address the broader issue of social order, which relates strongly to the ability to move forward post-crisis.

Keywords: Crystal Cathedral; Robert H. Schuller; Sheila Schuller Coleman; Christian megachurch ministry; Christian televangelism; crisis communication; crisis management; communications strategy; social order; public relations strategy; media and content analysis

Overview

Reverend Robert H. Schuller began preaching from the rooftop of an Orange County, California, drive-in theater in 1955. He preached positive Christian sermons accented by alliterative slogans and an ‘I’m ok, you’re O.K.’ philosophy (“Drive-in Devotion,” 1967; Mahler, 2005; “Retailing Optimism,” 1975). As Schuller gained a following among Southern Californians, he realized his message had the potential to resonate with a national and international audience (Ahlersmeyer, 1989; Greenblatt & Powell, 2007). In the years that followed, Schuller built an opulent, verdant campus with chapels, a school, an office complex, statuary gardens, and a 236-foot bell tower. He took his ministry to television and was soon attracting ten million viewers a week to his “Hour of Power” program (H. Miller, 2001). At the center of Schuller’s ministry was a unique all-glass sanctuary with 10,000 windows, seats for 2,700 people, and one of the world’s largest pipe organs (“History,” 2011). Built in 1980, the $18 million building was dedicated debt free (H. Miller, 2001), allowing Schuller’s Garden Grove Community Church to re-brand itself under the name of its new icon, The Crystal Cathedral.

In 2009, the lavish tapestry of Schuller’s ministry began unraveling. Schuller’s son and heir apparent, Robert A. Schuller, was installed as senior pastor and then removed. He was replaced by his sister, Sheila Shuller Coleman (“Schuller Picks Daughter,” 2009). Soon, family members who were on the payroll began quarreling privately and publicly (Oleszczuk, 2011). Financial donations to the ministry waned, and the ministry filed for bankruptcy. The Crystal Cathedral and all the land around it were sold to partially satisfy $43 million in creditor claims. By early 2012, Robert H. Schuller had resigned from the ministry he started, and all members of his family had either resigned or had been fired. The new owner of the property, the Roman Catholic Diocese of Orange, would take possession within three years – at which point even the name Crystal Cathedral would cease to exist.

Although crisis events involving prominent Christian televangelists are not uncommon (“Grassley Seeks,” 2007; T. W. Smith, 1992), which is explored below, the Crystal Cathedral case is unique. A series of events over a period of two years culminated in the dissolution of a 55-year old ministry that at its height was generating hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue annually. This example provides valuable insights into ways organizations should respond through the news media to topical events in a time of crisis. It also helps illustrate how religious groups and other similar organizations need to communicate with the media in ways that will facilitate the portrayal of competent, trustworthy organizational social order. As news media coverage of the Crystal Cathedral Ministry suggests, when ministry leaders are not able to do this, organizational stakeholders can quickly disengage their support because they will adopt the perspective taken by the news media (Coombs, 2007) and assume that the organization is not acting in their best interests.

Christian Televangelists

In November, 2007, U.S. Senator Charles Grassley [R-Iowa], ranking member of the Senate Finance Committee, contacted six prominent evangelical Christian ministers seeking “information on expenses, executive compensation and amenities given to executives and family members” (“Iowa Senator Continues,” 2009, p. 3). Although Robert H. Schuller was not among those queried, Grassley suggested many televangelists and their ministries were engaged in “lavish spending” (Salmon, 2008, p. A6). Grassley specifically noted televangelists’ frequent purchases of mansions, private jets, and expensive gifts (Gorski, 2008). Four of the six ministries investigated by Senator Grassley refused to cooperate with the investigation (Swanson, 2012).

Lack of accountability for financial dealings is not uncommon among prominent Christian evangelists. In the 1980s, televangelist Jim Bakker was indicted on fraud charges following a federal investigation. In the late 1990s, Kenneth Copeland Ministries was found to have paid $87,000 in cash and more than $1 million in benefits to ministry board members (“Televangelist’s Family Prospers,” 2008). Trinity Broadcast Network founder Paul Crouch and his family are alleged to have siphoned $50 million from ministry receipts (Dulaney, 2012; Lobdell, 2004); Joyce Meyer was the target of a newspaper investigative series claiming she pocketed $95 million in earnings in 2003 (Garber, 2008); and Oklahoman Robert Tilton was tagged as “the poster boy for crooked evangelists” (“The 35 Biggest,” 2009, para. 7) when an ABC News investigation found he cashed donation checks while sending letters and prayer requests to a recycling facility.

In all, more than $100 billion is given annually to religious organizations in the U.S. (Flandez, 2011), and, according to one expert, “it’s hard to say how the money is being spent” (Sforza, 2011, para. 25). Ministries as a whole are hesitant to offer accountability – and family-based Christian ministries are even less willing, according to Frankl (1990). This reluctance is because family-based ministries often expand beyond “family resources and interests of potential successors,” (p. 197), and their quest for revenue often overshadows ministerial outreach.

As with financial misdealing, family dissent is also common among prominent Christian evangelists. Georgia megachurch pastor Creflo Dollar was arrested at his home after allegedly choking and slapping one of his children (Hunter, 2012). Billy Graham’s son Franklin has been termed “a rhetorical and theological bully” as a result of his ongoing quest to be seen as most suited among his siblings to continue their father’s legacy (L. Miller, 2011, para. 10). Oral Roberts’ children and their spouses – both before and after Roberts’ death – were accused of misuse of resources, unethical conduct, and inappropriate political influence in the family ministry and university (Leclaire, 2012; Willard, 2007).

Unlike most crisis events involving prominent Christian ministers, the Crystal Cathedral situation became a perfect storm of financial crisis and family dissent. Unlike other situations in which crisis-plagued religious ministries still manage to stay in business, the crisis events faced by Robert H. Schuller’s ministry paved the way for the dissolution of the organization. Assessing how this case played out in the media is a worthwhile endeavor because it offers lessons that can be applied to the study of religious organizations as well as to the understanding of strategic public relations management and the communication of organizational social order.

Crisis Communication

Organizational crisis represents “a low-probability, high-impact situation that is perceived by critical stakeholders to threaten the viability of the organization and that is subjectively experienced by these individuals as personally and socially threatening” (Pearson & Clair, 1998, p. 66). In such a situation, an organization’s competence or honesty is threatened because some or all of the communication about the threat is outside the organization’s control (Lattimore, Baskin, Heiman, & Toth, 2007; R. D. Smith, 2009).

A crisis creates a need for information, particularly among members of the public who interact with the organization (Coombs, 2007). When crisis is addressed appropriately, organizations and their stakeholder publics can resume “mutually beneficial relationships” that are fundamental to good public relations (Elliott, 2012, para. 11).

When a well-publicized crisis situation is not handled well, organizational stakeholders can experience psychological stress. Stress occurs when stakeholders are not getting information about what has happened and do not know what is being done to protect them from similar crises in the future (Benoit, 1995; Coombs, 2006). An organization in crisis must make a timely, appropriate, consistent, and effective response (Guth & Marsh, 2006; R. D. Smith, 2009). Because a crisis involving any single business entity can draw public attention to the practices of an entire industry or market segment (Fortunato, 2011), the organization in crisis must be publicly accountable for any actions that may have allowed the crisis to develop or worsen (Weiner, 2006).

The organization’s ability to quickly put forward objective explanatory information will help lessen any possible emotional reaction of publics (Jin & Yeon, 2010). A presentation of clear, rational explanation can show the organization is willing “to create harmony” with its publics (R. D. Smith, 2009, p. 94).

An organization in crisis regains control by effectively balancing action-oriented communication with response to issues already raised by the news media or other sources. This shows that the organization understands what its opponents are thinking and that it can act to explain issues or refute untrue claims while moving the issue forward. In all cases, the organization should avoid “artful dodging” (R. D. Smith, 2009, p. 132), which is an effort to appear transparent while still withholding additional information needed by publics. Organizations that have crisis management plans in place tend to respond faster and more efficiently to unforeseen emergencies (Massey & Larsen, 2006).

Some researchers have noted the importance of making a strong strategic match between the types of information disseminated by an organization in crisis, and the media channel(s) used for that dissemination. An experimental study by Liu, Austin, and Jin (2011) suggests publics may be more supportive of some types of crisis response communication disseminated through traditional media than similar messages disseminated through social media:

This means that, all else being equal, selected information form and source must be considered in tandem with the crisis response strategy as distributing information via traditional media might not be as effective for all crises. (p. 351)

Much research is still being undertaken into how post-crisis communication plays out across different media types. Still, a strong argument has been made for active, coordinated engagement of communication through different media channels to engage affected stakeholders (Schwarz, 2012).

The final judgment on resolution of a crisis is likely to come through the media – and experience has shown that many members of the public will adopt the media’s perspective (Coombs, 2007). For this reason, it is critical that an organization in crisis immediately develops an effective working relationship with media gatekeepers and maintains that relationship until the crisis has been fully addressed and the organization has clearly shown how it is moving beyond the event.

Crisis Communication Research

We can learn much from case studies documenting how individuals and organizations dealt with crisis in the past. Even events that happened many years ago can still provide insight for dealing with emergencies today (Brummette, 2012). As a consequence, crisis communication literature is dominated by case studies – a situation that Coombs (2007) has noted with concern. Case studies do not allow for much documentation of the internal processes of the organization or the thinking of leadership as it reacts to crisis, nor do case studies allow for understanding how stakeholders respond when presented with new communication from organizations in crisis.

Coombs (2007) has offered his Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) as

an evidence-based framework for understanding how to maximize the reputational protection offered by post-crisis communication. … SCCT identifies how key facets of the crisis situation influence attributions about the crisis and the reputations held by stakeholders. In turn, understanding how stakeholders will respond to the crisis informs the post-crisis communication. (p. 163)

SCCT has merit because it allows for a classification of the response strategies to identify strategies that would potentially work best to assuage the concerns of stakeholders and protect the organization from backlash in a specific crisis situation. SCCT would work well as a strategic planning tool for organizations planning for crisis or at the onset of a crisis event.

At the same time, it is challenging to use SCCT as a tool to fully analyze past crisis events because key information that would be needed to explain the organization’s decision-making processes is likely unavailable. Organizations that have dealt with crises often do not welcome public communication about what transpired. An effort to use SCCT to look retrospectively at a crisis event would likely be frustrated in gaps in knowledge, as some information about the organization and its internal communication would not be available.

Social Order

One way to expand the usefulness of the case study approach is through application of the social order model (Duncan, 1962, 1968). Social order focuses on the action and communication of people in social groups. It allows us to see how people in power exert their power and offer communication to explain the actions that they and the social organizations they represent have taken. It is an appropriate construct to use in this particular case study for a variety of reasons, which are explained below.

Social order is both a contributor to and a construct of power. Social order is manifested through a division of labor, an establishment of trust among people in the social environment, a regulation of power that allows for decision-making to occur, and a set of systems that legitimize human activity (Cowan, 1997; Eisenstadt, 1992).

Social order is demonstrated through culture, or “an organized set of meaningfully understood symbolic patterns” (Alexander, 1992, p. 295). Social order is established and maintained through written and unwritten rules about appropriate conduct, including the use and sharing of power (Edgerton, 1985) and emotion (von Scheve, 2010).

Sociologists disagree on the finer points of social order – specifically, the impact of shared values in the formation of social order and whether social order can develop spontaneously or must be a result of action initiated by hierarchy (Crespi, 2008; Takahashi, 2009). For the purposes of this case study, however, these incidentals can be set aside. In the context of this case study, social order is appropriate because it recognizes that nothing happens by accident.; there is always some level of intention within a socially-ordered environment. Every choice that professionals make within organizations communicates something about the social order of their organization and how they want that organization to be perceived by others. Even the choice not to do something communicates something about the organization, because, as Duncan (1962) wrote, “a social order defines itself through disorder as well as order” (p. 281). The ideal socially ordered environment is one where people share power responsibly, communicate clearly, and work productively together no matter what cultural, economic, social, or technological uncertainties may develop.

We can all acknowledge that people desire stability and security in their lives. People have traditionally sought spiritual comfort through religious organizations and leaders who can provide stability by bringing order out of disorder (Kingsbury, 1937; Sass, 2000; Lugo et al., 2008). Ultimately, the stable outcomes that people seek through a religious experience are not unlike the desired outcome from a socially ordered experience. It is “compatibility of human needs, ends, values and intentions” (Višňovský, 1995, p. 110).

This research recognizes the value of a fusion of approaches. It takes the form of a case study, but it acknowledges the value of Coombs’ SCCT. It utilizes traditional content analysis of media. It holds to the position that a communication of competent, trustworthy organizational social order is essential to help an organization maintain relationships with stakeholders and move beyond its crisis.

Inquiry and Methodology

This case study illustrates how the Crystal Cathedral crisis played out in the news media. The researcher did not have access to ministry leaders or documents. So, rather than speculating about what was happening inside the organization, the focus is on what was published about it and how the portrayal of the Crystal Cathedral aligned with standards for effective crisis management and expectations of effective organizational social order.

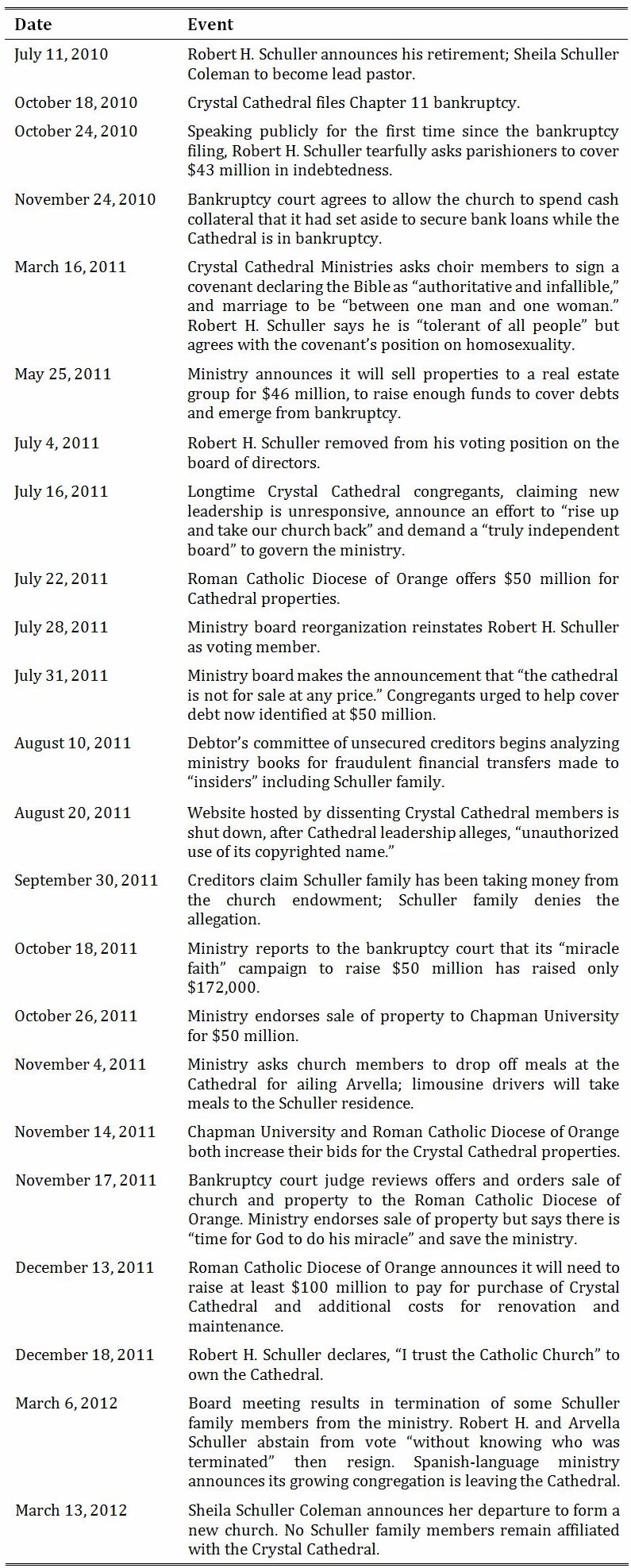

Data collection was focused wholly on news media narratives published between July 2010 and March 2012. During this period of time, the Crystal Cathedral was faced with 23 publicized crisis events, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Robert H. Schuller/Crystal Cathedral Ministry significant crisis events, July 2012-March 2012.News articles published during this time period were obtained through a Lexis/Nexis search. A general Internet search was not utilized because some news stories published during the 2010-2012 time frame were no longer available online. (Other stories disappeared from news media websites during the research process.) The initial Lexis/Nexis search for articles covering the Crystal Cathedral resulted in more than 900 items. After removing duplicates and editorially non-qualifying content, 80 news articles were isolated for study. These articles came from 15 secular and four Christian news media entities.

Each news article was reviewed by the author. Media content analysis was used to qualitatively and quantitatively assess story sourcing and attribution. Media frame analysis was used to characterize the subject focus of Crystal Cathedral leadership messages as communicated through the media narratives.

Analysis

This section will begin with a brief quantitative summary of the articles’ narrative content, including an analysis of direct quotes offered on behalf of Crystal Cathedral leadership. This section will then explain how news media narratives addressed ten specific topical issues. Throughout, the results show Crystal Cathedral’s crisis communication efforts through the media were minimal, subjectively ambiguous, and may have raised more questions than it resolved. The communication portrayed the ministry as embodying a fractured, discordant social order that would not lend itself to institutional survival after loss of the edifice with which the ministry was identified.

General analysis

The 80 articles contained an average of 1,116 words per article. The shortest article had 29 words; the longest had 2,410 words. The Crystal Cathedral’s financial predicament was the primary subject focus of about half of the articles (42, or 51%); the purchase offer and subsequent sale of the property to the Roman Catholic Diocese of Orange was the primary subject focus of 18 articles, or 23%; and the remainder of the articles focused on Schuller family dissent (5, or 6%), Crystal Cathedral congregant confusion or dissent (5, or 6%), ministry leadership succession (4, or 5%), or other issues (6 or 8.5%).

Almost half of the 80 articles (37, or 46%) contained no direct quotes from anyone within Crystal Cathedral leadership. Of the 33 articles, 41% did include a quote from a ministry leader or spokesperson, and Sheila Schuller Coleman was most frequently quoted (19 articles, or 24%). Robert H. Schuller was quoted directly in nine articles (11% of the total), and another spokesperson was quoted directly in 18 articles (23%). Nine articles (11% of the total) claimed one or more Schuller family members or ministerial spokespeople were solicited for comment but refused or were unavailable.

Direct quotes from Sheila Schuller Coleman and Robert H. Schuller comprised less than 1% of the total published word count. Almost half of the direct quotes were identified as coming from a statement rather than reporter interaction. Many of the same (or nearly identical) quotations were found in different articles throughout the sample set. Quotations were commonly found to be statements from Schuller books, such as “tough times never last, but tough people do.”

For the most part, media narratives suggest ministry leadership talking at members of the media, rather than talking with them. Narratives suggest no clearly communicated position by ministry leadership and reflect few facts offered by leadership in a way that could be identified as a decisive and appropriate ‘action’ or ‘response’ the might help ease the crisis (see R. D. Smith, 2009). Narratives reflect little communication to reassure followers that the Crystal Cathedral was redefining itself as an organization of order rather than disorder (see Duncan, 1962), so that it might survive beyond its bankruptcy. Ten categorical examples are presented here to illustrate.

Payments to “insiders”

On October 3, 2011, the Orange County Register published a story titled “Lawsuit: Schullers gained as Crystal Cathedral lost,” which featured extensive detail of financial gain by so-called “insiders” (Schuller family members) including “generous salaries, housing allowances and other benefits while the church struggled financially over the past nine years” (Bharath, 2011c, para. 1). The article concluded with two potentially damaging statements: 1) that Robert H. Schuller’s consulting firm had filed a debtor’s claim with the bankruptcy court seeking a $223,000 payment from the ministry for use of his sermons and slogans; and 2) that the ministry had borrowed more than $10 million from ministry endowment funds to pay for general expenses, which had been provided initially from “Hour of Power” television viewer contributions. Both claims were endorsed with direct quotes from Carol Schuller Milner, one of Schuller’s daughters.

Two days later, the Register published another article stating “Robert H. Schuller shot back in response” (Bharath 2011b, para. 1). Without mentioning Carol Schuller Milner by name, Schuller contended that all actions of the ministry “were undertaken in good faith, with the best interests of the Crystal Cathedral Ministries in mind, and upon the advice of [legal counsel]” (Bharath, 2011b, para. 3). Speaking directly of his compensation, Schuller said the “ministry has reaped great benefit from that agreement, far in excess of what it has paid” (Bharath, 2011b, para. 6). Among the 80 news media narratives analyzed for this research, this article was the only one to offer a detailed account of Robert H. Schuller’s perspective on any issue. It is interesting to note that during the course of this case study, links to the Bharath (2011b) article and several others within the sample set were removed from the Orange County Register site without explanation and are no longer available.

Responding to attack

Although he responded quickly and decisively to the claims about insider payments, Schuller chose not to respond to other condemning claims from another family member. In a Christian Century article titled “The Day the Crystal Cathedral Died” (Schuller-Wyatt, 2011), granddaughter Angie Schuller-Wyatt characterized her aunts and uncles as misguided, self-absorbed, and spiritually arrogant. Her extensive and detailed explanation of the crisis concluded with the observation that her family members “made a mockery of Christianity and the Crystal Cathedral” (2011, para. 10). Schuller-Wyatt’s allegations received extensive media attention and were repeated in numerous other media, but a public response by Robert H. Schuller was never offered.

Silencing the opposition

During the crisis, Crystal Cathedral congregants sought ways to communicate via the Internet about what was happening. Crystal Cathedral leadership was successful in silencing communication through one web-based forum. A website, CrystalCathedralMusic.net, set up and maintained by a former parishioner, was closed down after the ministry complained about use of the words Crystal Cathedral, “a copyrighted name” (Bharath, 2011a, para. 2). At least one blog, Penrod’s Pokes at the Passing Parade, was established to provide a forum for communication by former members but without indication that the ministry tried to censor it. Beyond claiming copyright infringement, the ministry leadership offered no other rationale for its actions to silence dissent among congregants.

The ministry’s debt

In 2010, the ministry announced it was $43 million in debt. Within months, the ministry was using a figure of $50 million, and leadership never explained the reported increase. None of the articles analyzed contained details of the ministry’s revenues, expenses, or budget, nor did they say how the debt was acquired. The only response was a repeated statement by Sheila Schuller Coleman: “Budgets could not be cut fast enough to keep up with the unprecedented rapid decline in revenue due to the recession” (Cathcart, 2010, p. 16). At this same point in time, Schuller Coleman was paraphrased as follows: “Coleman said the ministry’s most recent financial reports include the best cash flow in a decade” (“Crystal Cathedral Files,” 2010). If both statements were true, one could easily reach the conclusion that the ministry had been overspending for ten years, yet further explanation or elaboration was not offered.

The “huge mess” to clean up

In 2010, Robert H. Schuller said that his daughter “will be doing what I would be doing if I were in her shoes,” yet in the same Christian Century article, Sheila Schuller Coleman said, “Things are turning around slowly… I’ve had a huge, huge mess to clean up” (Fowler, 2010, p. 17). No elaboration was offered or any other article about what “the mess” was, if Schuller Coleman was doing what her father would have been doing.

People will understand

Shortly after the 2010 bankruptcy filing, ministry leadership endeavored to communicate through the media that day-to-day operations of the church would continue. Coupled with this proclamation was a statement from Sheila Schuller Coleman that sought to normalize the financial crisis: “Many of the persons who support our ministry are facing similar challenges, and when they hear our message of hope, they know we are speaking from a point of true understanding” (Fung, 2010, para. 6). Ministry supporters may have been comforted by the idea that its programs would continue, whereas others may have been offended by Schuller’s suggestion that what her wealthy family was facing was comparable to financial pressure felt by the general public.

Schuller family extravagance

In November 2011, the ministry reported that Robert H. Schuller’s wife, Arvalla, was homebound, suffering from pneumonia. Members of the congregation received an e-mail message from the ministry, asking for donations of specific types of meals. Congregants were to bring meals to the church so the food could be shuttled to the Schuller home by limousine. Supporters of the ministry may have been comforted by the idea that they could do something to help Mrs. Schuller in her hour of need, whereas others may have been questioned why the family that could afford a limousine and a chauffeur pleaded for potluck meals to be donated by congregants.

“Vision-casting”

In July 2011, Robert H. Schuller was voted off the governing board and given a role of “vision-casting” for the ministry (Banks, 2011, para. 4). At this time, Sheila Schuller Coleman said she would “continue to defer to his wisdom” (Banks, 2011, para. 7), which was consistent with the elder Schuller’s previous comment that Schuller Coleman would follow in his footsteps (Fowler, 2010). These statements may have been theologically comforting to some people, whereas others may have been troubled that the crisis-plagued organization seemed to suggest it would not alter its financial operations or strategy. The term “vision-casting” was not defined.

Waiting on God

Throughout the crisis, Crystal Cathedral leadership continued to claim that “a miracle from God” would save the ministry. Beginning in May 2011 and extending beyond the sale of the property by the bankruptcy court, church leadership continued to predict that divine intervention would keep the Crystal Cathedral in the ministry’s hands:

- “The cathedral is not for sale at any price.” (August 2011)

- “God has used it (bankruptcy) to turn the eyes of the world toward the Crystal Cathedral because He wants to make a big, bold statement.” (August 2011)

- “God is in control and orchestrating the church.” (October 2011)

- “Nothing is final until the escrow closes. There is still time for God to do his miracle.” (November 2011)

- “It’s not too late. There is still time for God to step in and rescue Crystal Cathedral Ministries.” (November 2011)

The statements offered no reassurance for anyone unwilling to accept that divine providence would provide enough money to cover the ministry’s debts. Two weeks before the court-ordered sale of the Crystal Cathedral, the ministry confirmed its “Miracle Faith” campaign to raise $50 million had raised just $172,775 (Santa Cruz, 2011a).

Preferred buyer

As the bankruptcy court received competing bids for the property, Crystal Cathedral leadership made seemingly contradictory statements about its preferred buyer. On October 27, 2011, Robert H. Schuller endorsed Chapman University’s offer (Santa Cruz, 2011a). Less than a month later, Schuller said Chapman’s offer involved secular use of the property that was “divergent to both the call of God and our denomination” (Kumar, 2011, para. 9). News stories did not clarify why Schuller found the sale to Chapman acceptable in October, but not in November. Further complicating the question was a quote offered in a December article, after the sale of the property to the Roman Catholic Diocese of Orange, in which Schuller said the sale to the Catholics “could have happened 20 years ago because I haven’t changed. … It’s who I have always been. … The Roman Catholic Church isn’t going to change its theologies. … I trust them” (Santa Cruz, 2011c, p. A19).

Members of the Crystal Cathedral congregation may have been comforted that Schuller was at ease with the sale of the building to the Catholic Church. Others may have wondered exactly what Schuller and his family felt about the sale and why family opinion seemed to change in the final weeks before the sale.

Discussion

As is the case with any research based employing content analysis, the results shown here reflect what was published. Results cannot reveal the strategic intent of communication by the Crystal Cathedral leadership, and this case study cannot assess the intent of reporters, the depth of their inquiry into source claims, the extent of the editing process, or the influence of other variables on the published content.

What the research findings can affirm is that as the news media reported on the Crystal Cathedral’s financial crisis, family conflict, and unsure future, the Schullers and their ministry presented faith in God as the only answer and one that seemingly required no explanation or elaboration. While this may be theologically sound, it offers no objective or rational explanation. While some Crystal Cathedral congregants would likely embrace an exclusively “faith-filled” approach, other stakeholders would want rational explanations, as well – particularly since the ministry admitted that in recent years it spent at least $43 million in excess of receipts.

Leadership’s declaration of faith in God was never matched with an equal expression of human accountability for what the media continually characterized as poor financial stewardship. Robert H. Schuller seemed a mostly insignificant player in the drama surrounding his church, and media stories portrayed Sheila Schuller Coleman as the new leader who communicated no human plan for the present or vision for the future.

Schuller Coleman’s statement, “Budgets could not be cut fast enough to keep up with the unprecedented rapid decline in revenue due to the recession” (Cathcart, 2010, p. 16). She accepted no responsibility for the situation, offered no proof of the effort to cut, gave no detail on how much needed to be cut, and made no apology to congregants for the financial shortfall.

Promises that God would save the ministry were hopeful and consistent with the Schuller theology, but they did not address the business realities presented by a multi-million dollar debt or continuing reports of family squabbling. The ministry’s statements did not indicate that change was forthcoming; indeed, they communicated that the transition from Robert H. Schuller to Sheila Shuller Coleman would involve no change. Stakeholders could easily have surmised that no change meant the organization would continue to be mired in crisis, regardless of who was preaching from the pulpit.

After the sale to the Catholic Diocese, two Crystal Cathedral congregants were quoted: One said he was “devastated;” another felt “thrown under the bus” (Santa Cruz, 2011b, p. AA5). It was unclear whether the congregants blamed the bankruptcy court, the Catholic Church, Crystal Cathedral leadership, or the Schuller family. Congregants’ claims were not rebutted or explained by Crystal Cathedral leadership.

Situational Crisis Communication Theory allows us to categorize crisis types by “clusters” (Coombs, 2007, p. 168). In accordance with Coombs’ structure, news narratives reflect that Crystal Cathedral leadership portrayed its crisis as within the “victim” and “accidental” clusters. In other words, leadership portrayed itself as a victim of circumstance while simultaneously communicating that organizational actions precipitating the crisis were unintentional. This portrayal does not suggest a strong, engaged social order as social order has been previously defined.

Leadership never offered any communication to suggest that it knowingly took inappropriate actions, but an analysis of the 80 news articles reflects that the overwhelming perspective offered by other sources is just the opposite: the ministry did, indeed, knowingly take inappropriate actions, including but not limited to borrowing $10 million from trust funds to pay for day-to-day expenses. Throughout the time period of the crisis, news media narratives reflect insufficient refutation by Crystal Cathedral leadership to contrary claims from numerous other sources.

In her 2007 book Everyday Religion, Nancy Ammerman (2007) offered three questions about religious organizations in today’s world: “1) Are they vigorous social communities where bonds of solidarity are created and reinforced?; 2) Are they creative mobilizers and networkers?; and 3) Do they train and support leaders who can articulate compelling visions?” (p. 233).

The Crystal Cathedral leadership was unsuccessful in using the media to portray the ministry as embodying a vigorous social community. Media narratives portrayed the Schuller family as a wealthy group with conflicting objectives, and frequent media usage of the term “insiders” reinforced the concept of the Schullers being apart from their followers. Media narratives offered almost no ‘voice’ of the followers, either individually or as a collective congregation.

Leadership was unable to use the media to communicate to stakeholders a vision of what the future would hold. For the most part, what was communicated was hope beyond hope – that somehow God would “save the Crystal Cathedral” even as donations from its legions of followers did not.

In March 2012, Sheila Schuller Coleman resigned from her leadership of the Crystal Cathedral and immediately announced formation of a new ministry. This new endeavor, “Hope Center of Christ Orange County,” had no home, no identified programmatic focus, and offered no public identity beyond the name and address of the movie theater where it would meet (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Screen shot of the Hope Center of Christ Orange County website, at http://hopecenteroc.org, captured March 2012.Meanwhile, having excised itself of all members of the Schuller family, those who remained in leadership positions within the Crystal Cathedral were not identified by name in the media. Who, exactly, was making decisions and how those decisions were being made remained unstated. Photos of members of the Schuller family were quickly removed from the Crystal Cathedral website (see Figure 2).

The methodology of this research makes it impossible to know for certain whether the lack of assertiveness, clarity, and detail in Crystal Cathedral leadership’s communication was the result of sparing comments by leadership or broad editing by gatekeepers. However, the sample set of news stories encompassed 80 unique articles from 19 news sources. If the ministry had worked strategically and proactively to regain control of the communication, it is difficult to imagine that there would not have been more stories, greater word count, more ministry sources offered, and much more direct quotation of leadership. If at any point during the crisis period Robert H. Schuller had offered the media ‘his side of the story’ in depth and detail, it’s hard to imagine that the media would not have given it extensive coverage.

Discussion Questions

- What might be some reasons for Crystal Cathedral leadership – or any nonprofit, charitable, or religious organization – to reject the concept of using the media to proactively acknowledge its failure to deal with financial crisis and internal dissent?

- Are there virtuous reasons for an organization to remain silent when engulfed in a crisis that threatens its very survival? What might they be?

- Is it possible that a charismatic leader’s embrace of ‘positive thinking’ is so pervasive that it is impossible for the organization to realize how un-refuted claims in uncontrolled media communication threaten its institutional survival? Is this ‘groupthink,’ or does it go deeper than that?

- Many faithful congregants supported the Schullers and the ministry to the very end, yet the ministry made little effort to direct news media focus to these people and their stories. Would doing so have been an effective communication tactic? Why or why not?

- If you were in charge at the Crystal Cathedral and could wind the clock back to an earlier point in the series of events (Table 1), how would you communicate more assertively through the media about topical issues of the crisis? How would you communicate more assertively to portray the Crystal Cathedral as embodying a cohesive, caring social order?

References

The 35 biggest pop culture moments in modern Dallas history. (2009, December 16). D Magazine [Online]. Retrieved December 31, 2012, from http://www.dmagazine.com/Home/D_Magazine/2010/January/The_35_Biggest_Pop_Culture_Moments_in_Modern_Dallas_History.aspx

Ahlersmeyer, T. R. (1989). The rhetoric of reformation: A fantasy theme analysis of the rhetorical vision of Robert Harold Schuller. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Bowling Green State University.

Ammerman, N. T. (2007). Studying everyday religion: Challenges for the future. In N. T. Ammerman (Ed.), Everyday religion: Observing modern religious lives (pp. 219-238). New York: Oxford University Press.

Banks, A. M. (2011, July 5). Schuller loses vote at Crystal Cathedral. The Christian Century. Retrieved December 31, 2012, from http://www.christiancentury.org/article/2011-07/schuller-loses-vote-crystal-cathedral

Benoit, W. L. (1995). Accounts, excuses, and apologies: A theory of image restoration strategies. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Bharath, D. (2011a, August 20). Crystal Cathedral congregants’ website shut down. Orange County Register. Retrieved December 31, 2012, from http://www.ocregister.com/articles/cathedral-313168-crystal-church.html

Bharath, D. (2011b, October 5). Crystal Cathedral’s Schuller: Suit claims vs. family unfair. Orange County Register. Retrieved December 31, 2012, from http://pens-opinion.org/schuller-shoots-back.html

Bharath, D. (2011c, October 3). Lawsuit: Schullers gained as Crystal Cathedral lost. Orange County Register. Retrieved December 31, 2012, from http://www.ocregister.com/articles/schuller-320176-church-milner.html

Brummette, J. (2012). Trains, chains, blame, and elephant appeal: A case study of the public relations significance of Mary the Elephant. Public Relations Review, 38(3), 341-346.

Cathcart, R. (2010, October 19). California’s Crystal Cathedral files for bankruptcy. The New York Times, p. 16.

Coombs, W. T. (2007). Protecting organization reputations during a crisis: The development and application of situational crisis communication theory. Corporate Reputation Review, 10(3), 163-176.

Coombs, W. T. (2006). Crisis management: A communicative approach. In C. H. Botan & V. Hazleton (Eds.), Public relations theory II (pp. 171-197). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Cowan, R. S. (1997). A social history of American technology. New York City: Oxford University Press.

Crespi, I. (2008). Il problema dell’ordine sociale in Talcott Parsons e Harold Garfinkel [The social order issue in Talcott Parsons and Harold Garfinkel]. Studi di Sociologia, 46(3), 329-351.

Crystal Cathedral files for bankruptcy protection. (2010, October 19). The Christian Century. Retrieved December 31, 2012, from http://www.christiancentury.org/article/2010-10/crystal-cathedral-files-bankruptcy-protection

Drive-in devotion. (1967, November 3). Time, p. 105.

Dulaney, J. (2012, February 24). Sinful sex at TBN and a motorhome for Jan Crouch’s dogs alleged in lawsuit. OC Weekly. Retrieved December 31, 2012, from http://blogs.ocweekly.com/navelgazing/2012/02/sex_tbn_santa_ana_crouch_mcveigh_koper.php

Duncan, H. D. (1968). Symbols in society. New York: Oxford University Press.

Duncan, H. D. (1962). Communication and social order. New York: Oxford University Press.

Edgerton, R. B. (1985). Rules, exceptions, and social order. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Eisenstadt, S. N. (1992). The order-maintaining and order-transforming dimensions of culture. In R. Munch & N. J. Smelser (Eds.), Theory of culture (pp. 64-88). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Elliott, S. (2012, March 1). Public relations defined, after an energetic public discussion. The New York Times. Retrieved December 31, 2012, from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/02/business/media/public-relations-a-topic-that-is-tricky-to-define.html?_r=1&ref=business

Flandez, R. (2011, March 21). Religious fundraising faces a ‘crisis,’ says speaker. Prospecting. Retrieved December 31, 2012, from http://philanthropy.com/blogs/prospecting/religious-fund-raising-faces-a-crisis-says-speaker/29254

Fortunato, J. (2011). Dancing in the dark: Ticketmaster’s response to its Bruce Springsteen ticket crisis. Public Relations Review, 37(1), 77-79.

Fowler, L. (2010, September 7). After public family feud, another Schuller steps up. The Christian Century, p. 17.

Frankl, R. (1990). Teleministries as family businesses. Marriage & Family Review, 15(3-4), 195-205.

Fung, K. (2010, October 19). Hour of Power church succumbs to Ch. 11. The Daily Deal. Retrieved December 31, 2012, from http://www.thedeal.com/2010/

Garber, K. (2008, February 15). Investigating televangelist finances: Does preacher Compensation violate non-profit tax laws? U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved December 31, 2012, from http://www.usnews.com/news/national/articles/2008/02/15/investigating-televangelist-finances

Gorski, E. (2008, January 18). Senator to continue televangelist probe. The Tulsa World, p. C12.

Grassley seeks information from six media-based ministries [Press release]. (2007, November 6). U.S. Senate Committee on Finance. Retrieved December 31, 2012, from http://www.finance.senate.gov/newsroom/ranking/release/?id=baa4251a-ee70-48af-a324-79801cd07f18

Greenblatt, A., & Powell, T. (2007, September 21). Rise of megachurches. CQ Researcher, 17, 769-792.

Guth, D. W. & Marsh, C. (2006). Public relations: A values-driven approach (3rd ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

History 1955 to today. (2011). Crystal Cathedral Ministries. Retrieved December 31, 2012, from http://www.crystalcathedral.org/about/history.php

Hunter, J. (2012, June 11). Creflo Dollar denies choking allegations in sermon. The Washington Post. Retrieved December 31, 2012, from http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/under-god/post/creflo-dollar-denies-choking-allegations-in-sermon/2012/06/11/gJQAUCipUV_blog.html

Iowa senator continues televangelist probe. (2009, May). Church & State, p. 3.

Jin, Y., & Yeon, S. (2010). Explicating crisis coping in crisis communication. Public Relations Review, 36(4), 352-360.

Kingsbury, F. (1937). Why do people go to church? Religious Education, 32, 50-54.

Kumar, A. (2011, November 21). Crystal Cathedral still believes God can save campus. The Christian Post. Retrieved December 31, 2012, from http://www.christianpost.com/news/crystal-cathedral-believes-god-can-save-campus-62499/

Lattimore, D., Baskin, O., Heiman, S., & Toth, E. (2007). Public relations: The profession and the practice (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

Leclaire, J. (2012, May 4). Oral Roberts’ son gets probation in DUI case. Charismanews. Retrieved December 31, 2012, from http://charismanews.com/us/33343-oral-roberts-son-gets-probation-in-dui-case

Liu, B. F., Austin, L., & Jin, Y. (2011). How publics respond to crisis communication strategies: The interplay of information form and source. Public Relations Review, 37(4), 345-353.

Lobdell, W. (2004, September 12). Televangelist Paul Crouch attempts to keep accuser quiet. The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 31, 2012, from http://www.trinityfi.org/press/latimes03.html

Lugo, L., Stencel, S., Green, J., Smith, G., Cox, D., Pond, A., … & Ramp, H. (2008, June). U.S. religious landscape survey: Religious beliefs and practices: Diverse and politically relevant. Washington, DC: Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. Retrieved December 31, 2012, from http://religions.pewforum.org/pdf/report2-religious-landscape-study-full.pdf

Mahler, J. (2005, March 27). The soul of the new exurb. The New York Times Magazine [Online]. Retrieved December 31, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2005/03/27/magazine/327MEGACHURCH.html?_r=0

Massey, J. E., & Larsen, J. P. (2006). Crisis management in real time: How to successfully plan for and respond to a crisis. Journal of Promotion Management, 12(3/4), 63-97.

Miller, H. (2001, March/April). Living on the edge. Saturday Evening Post, pp. 36-39, 78.

Miller, L. (2011, May 15). The fight over Billy Graham’s legacy. The Daily Beast. Retrieved December 31, 2012, from http://www.thedailybeast.com/newsweek/2011/05/15/the-fight-over-billy-graham-s-legac.html

Oleszczuk, O. (2011, October 5). Crystal Cathedral bankruptcy: Schuller denies allegations in lawsuit filed by creditors. The Christian Post. Retrieved December 31, 2012, from http://global.christianpost.com/news/crystal-cathedral-bankruptcy-schuller-denies-allegations-in-lawsuit-filed-by-creditors-57321/

Pearson, C. M., & Clair, J. A. (1998). Reframing crisis management. Academy of Management Review, 23(1), 59-76.

Retailing optimism. (1975, February 24). Time, p. 44.

Salmon, J. L. (2008, May 25). Televangelist probe under fire from right. The Washington Post, p. A6.

Santa Cruz, N. (2011a, October 31). Churchgoers still pray for a miracle. The Los Angeles Times, p. AA3.

Santa Cruz, N. (2011b, November 18). Diocese to get Crystal Cathedral: A bankruptcy court OKs the $57.5-million sale to the Catholic Church, a blow to Chapman University. The Los Angeles Times, pp. AA1, AA5.

Santa Cruz, N. (2011c, December 18). O.C. diocese comes of age with cathedral deal. The Los Angeles Times, pp. A1, A19.

Sass, J. S. (2000). Characterizing organizational spirituality: An organizational communication culture approach. Communication Studies, 51(3), 195-217.

Schuller picks daughter to lead Crystal Cathedral. (2009, July 14). The Christian Century, p. 17.

Schuller-Wyatt, A. (2011, November 21). The day the Crystal Cathedral died. The Christian Post. Retrieved December 31, 2012, from http://www.christianpost.com/news/the-day-the-crystal-cathedral-died-62568/

Schwarz, A. (2012). How publics use social media to respond to blame games in crisis communication: The love parade tragedy in Duisburg 2010. Public Relations Review, 38(3), 430-437.

Sforza, T. (2011, January 19). Senate probe praises televangelist; Benny Hinn of Dana Point receives kudos in a report on financial practices and transparency at ministries. Orange County Register. Retrieved December 31, 2012, from ProQuest, Document Number: 2242776821.

Smith, R. D. (2009). Strategic planning for public relations (3rd ed.). New York: Routledge.

Smith, T. W. (1992). Poll trends: Religious beliefs and behaviors and the televangelist scandals of 1987-1988. Public Opinion Quarterly, 56(3), 360-380.

Swanson, D. J. (2012). Answering to God, or to Senator Grassley?: How leading Christian health and wealth ministries’ website content portrayed social order and financial accountability following a federal investigation. Journal of Media and Religion, 11(2), 61-77.

Takahashi, S. (2009). Interaction theory of E. Durkheim: A comparison of the social order theories of E. Durkheim, T. Parsons, and H. Garfinkel. Shakaigaku Hyoron/Japanese Sociological Review, 60(2), 209.

Televangelist’s family prospers from ministry (2008, July 26). The Associated Press. Retrieved December 31, 2012, from http://www.rickross.com/reference/kcm/kcm8.html

Višňovský, E. (1995). Social order and human nature. Human Affairs, 5(2), 110-118.

von Scheve, C. (2010). Die emotionale struktur sozialer interaction: Emotionsexpression und soziale ordnungsbildung [The emotional structure of social interaction: The expression of emotion and the emergence of social order]. Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 39(5), 346-362.

Weiner, B. (2006) Social motivation, justice, and the moral emotions: An attributional approach. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Willard, A. (2007). The Oral Roberts University scandal from students’ perspectives. Yahoo! Voices. Retrieved December 31, 2012, from http://voices.yahoo.com/the-oral-roberts-university-scandal-students-595575.html?cat=4

DOUGLAS J. SWANSON, Ed.D., APR, is an associate professor in the Department of Communications at California State University, Fullerton. Email: dswanson[at]fullerton.edu.

Declaration

This research was not designed to make moral judgments about Christian televangelist ministries in general, or Robert H. Schuller’s ministry in specific. This research represents no critique of theology or religious practice. The author’s interest was solely in characterizing the communication through the media by Schuller and his ministry and identifying the extent to which that communication was or was not consistent with appropriate public relations crisis response and portrayal of competent, trustworthy organizational social order.

Editorial history

Received March 19, 2012

Revised June 12, 2012

Accepted September 23, 2012

Published December 31, 2012

Handled by editor; no conflicts of interest