To cite this article

Kruvand, M., & Silver, M. (2013). Zombies gone viral: How a fictional zombie invasion helped CDC promote emergency preparedness. Case Studies in Strategic Communication, 2, article 3. Available online: http://cssc.uscannenberg.org/cases/v2/v2art3

Access the PDF version of this article

Zombies Gone Viral:

How a Fictional Zombie Invasion Helped CDC Promote Emergency Preparedness

Marjorie Kruvand

Loyola University Chicago

Maggie Silver

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Abstract

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s annual social media campaign to encourage Americans to prepare for natural disasters and other emergencies usually attracts little more than a yawn. So in 2011, agency communicators tapped into the white-hot popularity of zombies to spice up old-school preparedness advice and create a low-cost campaign that was anything but boring. The campaign quickly went viral, with nearly 5 million people viewing the agency’s zombie apocalypse blog post and media organizations around the world covering the phenomenon. CDC communicators were caught off guard by the campaign’s popularity but made the most of it by developing and implementing a variety of additional strategic communication tactics to extend the campaign’s reach and longevity.

Keywords: zombie apocalypse; emergency preparedness; social media campaign; U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; public health; strategic communication; case study

Introduction

How do you get people to think about, and act on, a subject few like to consider? How do you make a social media campaign on a serious topic stand out? Those are the challenges that Dave Daigle, associate director for communications in the Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and his team faced in spring 2011. Each year, prior to the beginning of hurricane season on June 1, the federal health agency attempts to educate Americans about how to prepare for natural disasters and other emergencies. But CDC officials acknowledge that in most years, its efforts were staid, sober, and mainly overlooked. As Daigle explained, “We put out the same messages every year, and I wonder if people even see those messages” (as cited in Good, 2011).

Daigle hoped to come up with a fresh idea for 2011 to help cut through cyber clutter and jar public apathy about emergency preparedness. So he and two colleagues, Catherine Jamal and Maggie Silver, brainstormed possible campaign themes to prompt more people to take notice. Jamal remembered that activity on the CDC’s Twitter account, @CDCEmergency, had spiked after the meltdown in March 2011 at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant in Japan. At the time, CDC had asked followers what emergencies they were prepared for, and agency communicators were surprised when many followers said “zombies.” From that, the idea of a zombie apocalypse campaign was born. But no one, including the CDC communicators themselves, could have predicted the long-lasting viral sensation the campaign would become – crashing one of CDC’s web servers, sparking widespread national media attention, and spawning copycat public service campaigns and activities throughout the country. The zombie tie-in was all it took to “set off an Internet frenzy over tired old advice about keeping water and flashlights on hand in case of a hurricane” (Stobbe, 2011).

Background and Literature

CDC, which is headquartered in Atlanta, Georgia, is part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. CDC describes itself as “the nation’s premier public health agency — working to ensure healthy people in a healthy world” (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2010b.). Its mission is: “Collaborating to create the expertise, information, and tools that people and communities need to protect their health – through health promotion, prevention of disease, injury and disability, and preparedness for new health threats” (CDC, 2010a). CDC has more than 15,000 employees in more than 50 countries (CDC, 2010b.). The Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response (OPHPR) is one of five offices in CDC and is responsible for all of the agency’s public health preparedness and response activities on threats ranging from influenza epidemics to outbreaks of food-borne illness to serious natural disasters (CDC, 2012b). Dr. Ali S. Khan, a physician and retired U.S. assistant surgeon general, is its director.

Although OPHPR has an annual budget of $1.4 billion, much of it is distributed to state and local programs and to other initiatives across CDC to aid and promote national health security. The communication office in OPHPR is relatively small. Six communicators worked there in spring 2011: Three communication specialists and two web developers, led by Daigle. The majority of funding for the communication office goes for staff salaries and operating costs, leaving the remainder for communication activities and campaigns. As a result, the communication team relies heavily on social media, web-based communication, and partnership efforts to extend the reach of public health campaigns.

The communication team’s primary responsibilities are media relations, public health messaging, internal communication, and social and digital media. In partnership with communicators in the Emergency Risk Communication Branch, the team helps maintain CDC’s emergency preparedness and response website, Facebook page, Twitter feed (@CDCEmergency) and listserv (GovDelivery). The team also supports the communication activities of the director, including writing speeches, developing presentations, and staffing conferences. In addition, the team regularly updates content on the Public Health Matters blog, one of the most read blogs in the federal government and a top-50 blog on public health issues (CDC, 2012d).

Emergency preparedness has been defined as “the capability of the public health and health care systems, communities, and individuals, to prevent, protect against, quickly respond to, and recover from health emergencies, particularly those whose scale, timing, or unpredictability threatens to overcome routine capabilities” (Nelson, Lurie, Wasserman & Zakowski, 2007, p. S9). The more prepared a population is for an emergency, the more effective response to and recovery from a disaster will be (Solomon, 2008). The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 and Hurricane Katrina in 2005 revealed serious shortcomings in emergency preparedness and reinforced the need for all Americans to be educated, engaged, and mobilized as active participants (Nelson et. al., 2007). As a result, federal agencies such as CDC and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), state and local emergency management agencies, and the American Red Cross have been disseminating an old message with renewed urgency: encouraging Americans to prepare now so they can either evacuate quickly and safely or survive for several days until help arrives and utilities are restored.

These efforts have been only partly successful, however. Although public service campaigns have widely disseminated preparedness messages, and may even be credited for raising public awareness of the need for preparedness, they have not resulted in greater readiness. Despite the fact that 85% of Americans believe it is important to be ready for emergencies (American Red Cross, 2010), “current efforts are failing to increase the number of people actually taking steps to ensure their families are prepared” (Veil, Littlefield, & Rowan, 2009, p. 450). Surveys show that only a minority of Americans is even partly prepared (American Red Cross, 2010; Federal Emergency Management Agency Citizen Corps, 2009; National Geographic Channel, 2012), and the percentage has remained steady or even declined over the last few years (American Red Cross, 2010). Americans also tend to over-estimate their preparedness level. Although 66% of Americans surveyed by the American Red Cross in 2010 said they are very or somewhat prepared for a disaster, many are less prepared than they believe: 39% have an emergency kit, 10% are fully prepared (which the organization defines as having an emergency kit, having and practicing an emergency plan, and completing first aid training), and 26% have not taken a single action (American Red Cross, 2010).

Scholars note that “encouraging people to feel worried about emergencies that have not occurred is profoundly difficult” (Veil et al., 2009, p. 450). Lack of knowledge is one challenge: 27% of Americans said they did not know what to do to prepare (National Geographic Channel, 2012). Another challenge is psychological: “Many people simply don’t want to live in a culture of preparedness. The notion is off-putting, and downright scary for some, because it seems to place fear and defensiveness at the center of our public and private lives” (Klinenberg, 2008, p. A15). Since the need for preparedness is not a matter of if, but of when, there is much at stake in finding effective ways to educate Americans about preparedness and encourage them to get ready. This includes trying new approaches to reach a public that is largely complacent about preparedness and may find the topic disconcerting.

Research

At their brainstorming session in late April 2011, Daigle, Jamal, and Silver jotted down ideas on a white board. The three decided to target a younger demographic in 2011 – a demographic often overlooked by government agencies in previous communication efforts on emergency preparedness – with a social media campaign linking preparedness to a fictional zombie apocalypse. Daigle stuck his head in Khan’s office and briefly proposed the idea. “Most directors would have thrown me out of their office,” Daigle said (as cited in Stobbe, 2011). Instead, Khan’s reaction was positive; he told Daigle to “show me a concept.” The communication team did not conduct audience research or message testing, but did research the history and popularity of zombies.

According to Caribbean voodoo legends, a zombie is a dead person brought back to some appearance of life by a supernatural force, usually for an evil purpose (Gross, 2009). But zombies are the undead: they cannot speak, have no will of their own, and move rigidly and awkwardly. They walk the earth in search of human blood and brains to fortify themselves. While representations of zombies have been around for 80 years – they first staggered onto movie screens in 1932 (Gross, 2009) – they have been undergoing a resurgence in American pop culture (“Zombies Rise,” 2011). In fact, “zombies are a 20th-century pop‑culture phenomenon who have muscled into in the early 21st century” (Miller, 2012). There are zombie-themed races, games, and survival camps, and zombies have been featured in music, videos, books, and scores of movies. In October 2013, 16.1 million viewers watched the premiere of the fourth season of the AMC zombie series, “The Walking Dead,” making it the most‑watched basic cable drama telecast ever (Hibberd, 2013). Interestingly, the fictional headquarters of CDC exploded at the end of the first season of the show after a group of survivors attempted to take refuge there (McKay, 2011).

Daigle’s first internal email about the proposed theme, sent on April 27, 2011, had the subject line, “Zombie preparedness campaign.” The email began:

I recognize this is a strange subject line. Consider how many times you have been told to stock canned goods and three days of water as well as flashlights, etc. in your home for preparedness – that is such a tired message. Now imagine if we launched a Zombie Preparedness Campaign (tongue in cheek) saying those same messages (which would make sense if/when zombies attack). Zombies are incredibly hot and I think this would take off. (Daigle, personal communication, 2013)

Strategy

To achieve CDC’s objective of raising awareness of emergency preparedness and engaging teens and young adults on the topic, the campaign strategy called for using humorous, messages to communicate credible information. By pairing the agency’s traditional preparedness advice with a pop-culture phenomenon, the communicators hoped to spice up the notion of preparedness without changing the underlying how-to information. To disseminate the messages, the strategy relied on social media, which the communication team believed was quick, easy, and cost-effective, as well as the favored communication channel of the target audience. The entire campaign would be implemented by CDC employees. There was no set budget, no measurable goals, and no pre‑determined evaluation methods to determine if the campaign’s objectives had been met.

Daigle laid out the campaign strategy in an internal email sent on May 11, 2011:

Our goal is to engage this audience (one we have not engaged previously) on emergency preparedness and what steps they might take to prepare for an all hazards threat. We link and point to established tool kits, websites, and Red Cross and CDC guidance. We have an excellent window to leverage an all hazards campaign given the current flooding and a fast-approaching hurricane season. Ideally, we might draw mainstream media attention to this campaign and reach additional audiences. (Daigle, personal communication, 2013)

The cornerstone of the campaign would be a blog post, which would be reinforced and expanded upon by other social and digital media. At the time, CDC blogs were decentralized; the Public Health Matters blog was managed by the Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response. Because of this autonomy, Khan neither mentioned the campaign theme to other CDC leaders nor sought their approval. The plan called for posting the blog post on May 16, 2011, linking it to CDC’s emergency preparedness and response homepage, and sending the link to prominent news media organizations such as The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and CNN. On May 18, the communication team would send a tweet about the blog post, post about it on Facebook, and send information to subscribers of the GovDelivery listserv.

The plan’s timeline covered less than a week. “Looking further out (if the campaign is as successful as we think it will be) we would refresh the campaign during Preparedness Month with a Halloween hook,” Daigle wrote (personal communication, 2013). But the campaign lasted far longer, spread far wider, and involved many more facets than originally envisioned. The blog post, social media outreach, and extensive media coverage had a snowball effect that lasted well over a year. Daigle and his team took maximum advantage of the campaign’s popularity by planning and implementing many additional tactics to extend its longevity and reach.

Execution

The blog post (see Figure 1), which was written by Silver and approved by Khan, was a campy, tongue-in-cheek treatise on zombies interspersed with practical information about preparedness. Its overarching message was that if a person is prepared for a zombie apocalypse, they are prepared for any emergency. The post, “Preparedness 101: Zombie Apocalypse,” began:

Figure 1. Original CDC zombie apocalypse blog post.There are all kinds of emergencies out there that we can prepare for. Take a zombie apocalypse for example. That’s right, I said z-o-m-b-i-e a-p-o-c-a-l-y-p-s-e. You may laugh now, but when it happens you’ll be happy you read this, and hey, maybe you’ll even learn a thing or two about how to prepare for a real emergency. (CDC, 2011a)

The blog post provided the same emergency preparedness tips the CDC had offered in the past, but they were framed in terms of a zombie invasion:

Plan your evacuation route. When zombies are hungry, they won’t stop until they get food (i.e. brains), which means you need to get out of town fast! Plan where you would go and multiple routes you would take ahead of time so that the flesh eaters don’t have a chance! (CDC, 2011a)

After the post appeared on CDC’s Public Health Matters blog on May 16, 2011, “we waited two days to see if anyone got fired,” Daigle said (as cited in Weise, 2011b, p. 3A). When that did not happen, the communication team sent a tweet about the blog post (see Figure 2) and posted about it on Facebook.

Figure 2. Tweet about zombie apocalypse blog post.The server hosting the blog crashed nine minutes after the first tweet was sent on May 18, 2011, which was also the start of a two-day period of heavy media coverage. “Public health and preparedness are not sexy. But it turns out, zombies are,” Daigle said (as cited in Dizikes, 2011, p. A3). In addition to tweeting, Daigle and his team posted a similar message on Facebook, directing users to the blog post and sparking a lively discussion among users on personal preparedness (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Zombie apocalypse Facebook post.To capitalize on the attention sparked by the blog post, the CDC followed up primarily through digital media, which cost the budget-conscious communication team nothing. The agency offered buttons and badges – graphic elements that can be posted to any website, blog, social networking profile, or email signature to link users to more information about the zombie apocalypse campaign – as well as widgets – applications anyone can display on their website or blog (see Figure 4).

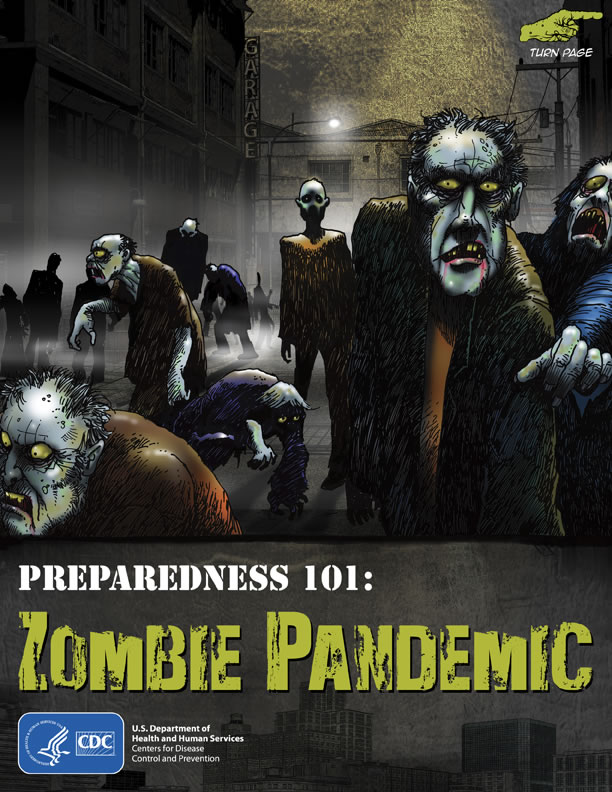

Figure 4. Zombie apocalypse campaign badge (top) and widget (bottom).In June 2011, CDC distributed zombie apocalypse posters and magnets. The following month, the CDC Foundation, a non-profit organization that supports the work of the CDC, began selling Zombie Task Force T-shirts online. In September 2011, the agency launched a preparedness video contest. And in October 2011, CDC created a 34‑page online graphic novella that combined a fictional horror story about a couple struggling to survive a zombie pandemic with a practical guide on how to prepare for any emergency (CDC, 2011e). Silver wrote it after several people emailed CDC with the suggestion, and it was designed and produced by CDC’s in-house graphic designers (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Cover of the zombie pandemic graphic novella.Due to the campaign’s popularity, Khan was invited in fall 2011 to speak at ComicCon in New York on “Zombie Summit: How to Survive the Inevitable Zombie Apocalypse,” and at Dragon*Con in Atlanta, where he was a panelist on the “These Are the Ways the World Will End” session (see Figure 6).[1] The Public Health Matters blog reported on both appearances. Khan said: “Zombies have been a really good way to get people to engage with preparedness … it served as a great bridge to talk about public health in general. All of a sudden, people are willing to hear about public health and how interesting it is, because we’ve mixed it with something they already want to hear about, zombies” (CDC, 2011d).

Figure 6. Dr. Ali S. Khan (right), director of the CDC Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response, speaks about preparing for a zombie apocalypse and other emergencies at the 2011 Dragon*Con convention in Atlanta. (Source: CDC)CDC also partnered with individuals, agencies, and businesses to further leverage the campaign through additional posts on the Public Health Matters blog. For example, the communication team developed a joint post with FEMA called “First there were Zombies; then came Hurricanes!” (CDC, 2011b). In addition, the blog featured a question-and-answer session with Max Brooks, author of The Zombie Survival Guide and World War Z: An Oral History of the Zombie War (CDC, 2011c). CDC also teamed up with AMC, the network that broadcasts the zombie television series “The Walking Dead,” on a blog post called “Teachable Moments – Courtesy of the Walking Dead on AMC,” which featured video clips from the show and preparedness advice sparked by the plot (CDC, 2012a).

For the one-year anniversary of the campaign, CDC used the theme “Zombie Nation” to showcase local zombie‑themed preparedness initiatives on the Public Health Matters blog between May 14 and 21, 2012. Examples included a post about an unusual class at Drexel University’s College of Nursing and Health Professions:

Class members were escorted to the morgue to help identify the undead, who, when the bags were unzipped, became reanimated … Unlike a typical classroom workshop using mannequins and actors portraying standardized patients, the students suddenly found themselves surrounded by – and tasked with helping – victims of a zombie attack. As the surprised group checked vital signs, some “patients” began to rise, stumble about and groan “braaaaaaains” … After ten minutes of growing chaos, a voice over the intercom called the scenario to an end. The stunned participants filed out of the simulation room and headed to a debriefing session. (CDC, 2012a)

In September 2012, CDC launched a learning website with a zombie theme for middle‑school teachers. CDC had received requests from teachers asking how to incorporate the campaign into the classroom, and CDC is interested in reaching children on the topic of preparedness because children can prompt their parents to become involved. The site provides lesson plans related to emergency preparedness, downloads of the zombie apocalypse poster and graphic novella, an emergency kit checklist, and ideas for games and activities, including a scavenger hunt (CDC, 2012c).

As the popularity of the zombie apocalypse campaign continued to grow, CDC turned down numerous other ideas and offers for partnerships and tie-ins – from Hollywood premiere parties to a book proposal – because they were deemed too commercial, not related closely enough to the agency’s preparedness mission, or ran the risk of diminishing the agency’s reputation.

Evaluation

CDC’s zombie apocalypse campaign went viral as quickly as some of the outbreaks of infectious disease the agency responds to. As one journalist commented, “Most of the time you don’t want to hear ‘viral’ and ‘CDC’ in the same sentence. Unless we’re talking in non‑medical terms” (Hassett, 2011). By May 19, 2011, three days after the “Preparedness 101: Zombie Apocalypse” blog post went live, it was receiving more than 60,000 views an hour. As of April 2013, the post has received more than 4.8 million views, compared to 1,000 to 3,000 views for typical posts on the Public Health Matters blog. The post has also generated 1,233 public comments, compared to an average of five comments on other posts on the same blog. Comments on the zombie apocalypse post ranged from kudos to additional preparedness tips:

Nice to see that there are some in our government that have both a brain and a sense of humor! This was quite possibly the only way you could have gotten me to visit the CDC website and actually read an emergency preparedness blog! (CDC, 2011a)

I love this post! My friends and I were discussing the zombie apocalypse after watching “Zombieland.” The discussion revolved around what we would do and how would we do it. It then dawned on us that what we were discussing would be extremely practical in real-world scenarios as well … I hope your article sparks many more discussions in many more homes across the country. (CDC, 2011a)

You just made government cool again. Applause for having the courage to actually do something creative to draw interest to an important subject, disaster preparedness. Well done! My favorite zombie survival tip … first ascend the staircase, then destroy it. (CDC, 2011a)

In addition, the campaign sparked a huge increase in the number of visits to the homepage of CDC’s emergency preparedness and response website; traffic increased by 1,143 percent in 2011 compared to 2010. CDC communicators cite that increase as evidence that the campaign helped raised awareness of preparedness. Zombie apocalypse badges and widgets also proved popular: there were 36,578 clicks to badges and 56 other websites hosted the campaign widget.

The campaign also lit up the Twitterverse (Marsh, 2011). CDC’s first tweet on May 18, 2011 resulted in 70,426 clicks and generated 34,714 unique tweets. “It was overwhelming. A tweet every second” Daigle said at the time (as cited in Bell, 2011). “We were trending yesterday! Things like the Royal Wedding trend. Not the CDC.” The @CDCEmergency feed gained more than 11,000 followers. Twitter also generated more than 1.1 million views of the blog post; users clicked on a link they saw on Twitter and were directed to the Public Health Matters blog.

CDC’s Emergency Preparedness and Facebook page gained more than 7,000 fans in the three weeks following the zombie apocalypse blog post. The Facebook page also sparked approximately 867 interactions – including likes, posts, and comments – by May 22, 2011. The majority of the interactions were positive; some were practical conversations between users about preparedness. For example, a visitor to the Facebook page posted:

I will be honest, my love for zombies … and Boy Scouts is what had me always being prepared no matter where I go … got a BoB in my car and a lot of stuff stocked up at home … plus a wealth of knowledge in my head for most any situation … glad to see something using pop culture now to promote things such as this … great tie in … and is sure to get a TON of attention.

When another visitor to the Facebook page asked what a “BoB” was, the author responded:

Bug out bag, a bag of items you need to survive for up to three days. Since I commute to work I keep mine in the car in case something happens during the commute or while I am away from home.

The graphic novella has been viewed more than 517,600 times. When Khan passed out copies at ComicCon, “they went like hot cakes,” Daigle said (as cited in Weise, 2011b). The preparedness video contest received 25 entries, many of which incorporated the zombie theme. The winner was the Burlington County Health Department in New Jersey, whose video was a spoof of the former MTV TV show “Jersey Shore.” CDC also distributed more than 18,500 zombie apocalypse posters. And the CDC Foundation sold approximately 5,000 Zombie Task Force T-shirts before the supply ran out.

The campaign generated extensive national media coverage, most of it positive. The atmosphere in the communication office was hectic: Although Daigle, Jamal, and Silver were used to fielding media inquiries, they had never had to handle so many so quickly. Requests for interviews came from as far away as Britain (“Centers for Disease Control Issue Official Guidelines,” 2011) and the Philippines (Suarez, 2011). More than 3,000 articles and news broadcasts were published or aired during the first week alone, reaching an estimated 3.6 billion viewers, according to monitoring reports obtained by CDC. “Zombie apocalypse” was second on Google’s list of “hot searches” the week the campaign was launched, and it was the most popular news story on CNN’s NewsPulse on May 20, 2011.

Adweek pronounced the campaign a “great marketing idea” (Cullers, 2011) while USA Today commented, “Never let it be said that the doctors at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention lack a sense of humor – or the sense to find a fun way to teach Americans about emergency preparedness” (Weise, 2011a). The Wall Street Journal explained that CDC was “looking for a clever way to get people to heed its advice on emergencies such as hurricanes – which on its own, let’s face it, is rather dry. The tactic seems to be working: the site announcing the new zombie preparedness plan crashed today” (McKay, 2011).

A number of news stories pointed out that the campaign was highly unusual for CDC. CNN commented, “The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is a big serious government agency with a big, serious job: protecting public health from threats ranging from hurricanes to bird flu. So when the good doctors of Atlanta warned people this week about how to prepare for a zombie apocalypse, the world took notice” (Greene, 2011). The Los Angeles Times stated that “the normally staid agency issued a straight-faced list of recommendations on how to survive a massive invasion of the flesh‑eating undead” (Li, 2011), while the Colorado Springs, CO, Gazette noted, “The CDC, a bureaucracy not known for having a sense of humor, managed to lighten up and recognize that humor is a powerful tool for public education” (Richardson, 2011).

Some in the media ridiculed the campaign, however. A news anchor at WGN‑TV in Chicago dismissed her station’s report on the campaign by saying on air, “This is baloney” (WGN-TV, 2011). Fox News host Bill O’Reilly called it one of the “dumbest things of the week” (O’Reilly, 2011). And an editorial in a small North Carolina newspaper commented: “We believe Khan’s time and our tax dollars could have been better spent providing instructions to readers on how to prepare for a real outbreak or hurricane or tornado” (“Wasted Time,” 2011). But the Colorado Springs, CO, Gazette noted: “What’s so great about this effort is that it cost the CDC all of $87 for a stock photo, and some staff time, rather than the millions spent on public information programs that nobody pays attention to” (Richardson, 2011).

Most – but not all – of the internal feedback on the campaign was favorable, including a positive note from Dr. Tom Frieden, director of CDC (Stobbe, 2011). Reaction within the preparedness community was enthusiastic as well. Daigle said FEMA and the American Red Cross have asked CDC how to develop similar initiatives. In addition, a number of state and local government agencies adopted the zombie apocalypse theme for their own public service campaigns. For example, the Kansas Adjutant General’s Department proclaimed October 2011 as Zombie Preparedness Month and urged residents to be ready for a zombie attack or other disasters (Ross, 2011). A department spokesperson noted: “We felt like this was a catchy idea and a new approach. I think this will help us draw some attention we might not get otherwise” (Ross, 2011). And officials in Delaware County, Ohio, held a zombie outbreak drill on Halloween 2011, with more than 225 volunteers dressing up as zombies (Franko, 2011). Emergency responders tested using standard decontamination procedures to treat the “zombies” and make them human again (Franko, 2011).

In September 2012, almost 400 emergency management officials from around the U.S. tuned in when FEMA held a webinar on “Zombie awareness: Effective practices in promoting disaster preparedness” (Lupkin, 2012). The announcement stated: “While the walking dead may not be first on your list of local hazards, zombie preparedness messages and activities have proven to be an effective way of engaging new audiences who may not be familiar with what to do before, during, or after a disaster, and to inject a little levity into preparedness while still informing and educating people” (Federal Emergency Management Agency, 2012).

The zombie apocalypse campaign received several awards. PR News gave CDC two Platinum PR Awards in 2011, one for the blog post and the other in the “Wow!” category (PR News, n.d.). The National Association of Government Communicators (2012) recognized the campaign twice in 2012, for “best blog” and “best campaign on a shoestring budget.” In addition, the campaign was one of six federal programs honored with an innovation award from the secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in 2012 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012).

Analysis and Discussion

Because “readying the public for the likely emergencies of the 21st century may be one of the most complex social-education challenges the nation has faced” (Solomon, 2008, p. B1), CDC communicators believed it was worth trying to inject some humor and pop-culture cachet into the topic, especially since the straightforward factual approach the agency had used in previous communication efforts had attracted scant public and media attention. Peter M. Sandman notes that much information about risk and safety is essential but boring:

To transmit boring information effectively, you need to overcome the boredom. That’s the most difficult part of what I call “precaution advocacy” – alerting apathetic people to serious risks and getting them to protect themselves appropriately. If you can arouse people’s interest or entertain them, you’ll get their attention … and then you won’t need so much repetition. You can overcome boredom by saying something that isn’t boring. It’s best if you can make the risk information you’re actually trying to impart interesting or entertaining in its own right. (2012).

The zombie apocalypse campaign began quite simply. “They put up a blog and a couple of tweets, and the rest is viral Internet history,” the Washington Post noted (Bell, 2011). One of the key lessons CDC communicators learned from the campaign is that popular public service campaigns can have humble beginnings. Daigle’s original plan, which called for a blog post, tweet, Facebook post, and listserv mention within a single week, was augmented by many other tactics planned and implemented over the following 16 months. These helped transform the campaign from a fleeting Internet sensation to a long-lasting phenomenon and a compelling example of successful strategic communications.

Because the Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response has a degree of autonomy within a much larger government agency and the communication team was small, decisions could be made quickly. The team’s nimbleness – its ability to react quickly, think ahead, plan, and scale up – proved to be one of its most important assets. Another lesson CDC communicators learned is that public service campaigns need not be expensive. Only internal staff resources were used on the campaign. Social and digital media, which cost nothing except staff time, was the mainstay of the campaign. The initial expense was $87 to buy stock photos used in the zombie apocalypse blog post and throughout the campaign. After CDC realized the campaign was a hit, an additional $20,000 was spent to print posters, post cards, and copies of the graphic novella to distribute to libraries, scout troops, schools, and other organizations requesting campaign materials.

Yet another takeaway from the campaign is that social media and the news media can have a synergistic effect in generating visibility for a public service campaign. Social media attention drove news media coverage of the zombie apocalypse campaign, which in turn generated more media coverage and more mentions in social media. In addition, the notion of a zombie apocalypse gained even more traction because of several unrelated, high-profile news events, including the prediction of a Christian radio host that judgment day would occur on May 21, 2011 (Praetorius, 2011), and a gruesome incident in Miami in which one homeless man chewed off part of the face of another in June 2012 (“Miami Police,” 2012).

But despite the popularity of the zombie apocalypse campaign, it is unclear whether the attention it garnered translated into motivation to prepare for emergencies, knowledge of what to do, and intent to take action. The objectives established for the campaign were part of the reason. CDC’s objectives were broad and indefinite – raising awareness of emergency preparedness and engaging teens and young adults on the topic – and no specific quantitative goals were set. In contrast, Stacks (2011) notes that three types of objectives should be established for public relations campaigns: informational objectives, motivational objectives, and behavioral objectives. Informational objectives determine what information is needed by the members of target audience and assess whether that information was received and understood. Motivational objectives gauge whether or not the information has impacted the attitudes, beliefs, or values of members of the target audience. And behavioral objectives determine whether the campaign has influenced the target audience to take specific intended actions (Stacks & Michaelson, 2010).

Due to the lack of concrete objectives, evaluating the campaign’s success was problematic. As Daigle noted, “Measuring the hits and views is great, but did people really make a plan, did we really affect behavior?” (as cited in Bell, 2011). No baseline research was conducted by CDC before the campaign to assess the existing level of emergency preparedness awareness, knowledge, and engagement among the target audience of teens and young adults. CDC conducted a small online survey during the campaign, but it asked web visitors simple close-ended questions and was not statistically valid. CDC communicators acknowledged that if they were planning the campaign today, they would focus more heavily on evaluation. The communicators simply were unprepared for such a huge initial response to the campaign as well as the amount of sustained interest in it for well over a year.

The novelty of the zombie apocalypse campaign is what made it so popular. But similar campaigns run the risk of becoming trite or stale, according to Bill Gentry, director of the community preparedness and disaster management program at the University of North Carolina’s school of public health (Stobbe, 2011). Gentry said that although CDC deserves credit for trying this kind of approach, it doesn’t mean the agency should start using vampires to promote vaccinations or space aliens to warn about the dangers of smoking. “The CDC is the most credible source out there for public health information,” he said. “You don’t want to risk demeaning that” (as cited in Stobbe, 2011). Daigle and his team understand this, and have carefully selected which zombie-related activities to pursue. Two years after the beginning of the zombie apocalypse campaign, zombies “live” quietly on the CDC website, while Daigle’s team looks for the next big idea to engage Americans on the subject of emergency preparedness.

Discussion Questions

- Public service communication campaigns typically present messages in a straightforward way or use fear appeals – persuasive messages that emphasize negative health or social consequences from failing to follow given recommendations – to raise awareness and change attitudes and/or behavior. CDC’s zombie apocalypse campaign differs because it uses humor. What other public service campaigns can you think of that use a lighthearted approach? Do you think they are effective? Why?

- In your opinion, does a tongue-in-cheek approach to a serious topic like emergency preparedness detract from the seriousness of the message? Why or why not?

- The zombie apocalypse campaign raised awareness of emergency preparedness, especially among a younger demographic CDC was trying to reach. But does awareness necessarily lead to education and action – knowing what to do prepare for an emergency and taking steps to do so, such as building an emergency kit and creating an emergency plan. Why or why not?

- A number of other government agencies have “piggybacked” on the popularity of CDC’s campaign by adopting public service campaigns with zombie themes. For example, the Illinois Department of Transportation distributed a video public service announcement for its “Click it or Ticket” campaign that showed a band of zombies attacking a motorist, who is saved by the seat belt he is wearing. If zombies are used in many different campaigns, what is the risk of target audiences developing “zombie fatigue”?

- With the benefit of hindsight, which method or methods would you have recommended to CDC prior to the launch of the zombie apocalypse campaign to measure the campaign’s effectiveness? Why?

Note

[1] ComicCon is a gathering of fans and creators of comic books, graphic novels, and games. Dragon*Con, which bills itself as “the largest multi-media, popular culture convention focusing on science fiction and fantasy, gaming, comics, literature, art, music, and film in the universe,” hosts several zombie‑themed events, including a zombie prom.

References

American Red Cross. (2010, December 30). Emergency preparedness. ‘Do more than cross your fingers’ campaign: Wave 3 research. Obtained electronically from Sharron J. Silva, director, market research, American Red Cross, June 22, 2012.

Bell, M. (2011, May 20). Zombie apocalypse a coup for CDC emergency team. Washington Post WorldViews [Weblog]. Retrieved April 3, 2013 from: http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/blogpost/post/zombie-apocalypse-a-coup-for-the-cdc-emergency-team/2011/05/20/AFPj3l7G_blog.html

Centers for Disease Control issue official guidelines to prepare for the world being taken over by … zombies. (2011, May 20). Daily Mail. Retrieved April 22, 2013, from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1388994/The-Zombie-Apocalypse-CDC-guidelines-issued-case-world-taken-walking-dead.html

Cullers, R. (2011, May 19). CDC’s blog post about zombies proves apocalyptic to website. Adweek Adfreak [Weblog]. Retrieved May 14, 2012, from http://www.adweek.com/adfreak/cdcs-blog-ppost-about-zombies-proves-apocalyptic-website-131795

Dizikes, C. (2011, May 20). Dying to get word out? CDC offers survival advice in zombie preparedness campaign. Chicago Tribune, A3.

Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2012, September 6). Zombie awareness: Effective practices in promoting disaster preparedness. Retrieved September 10, 2012, from http://www.citizencorps.gov/resources/webinars/zombieawareness.shtm

Federal Emergency Management Agency Citizen Corps. (2009). Personal preparedness in America: Findings from the 2009 Citizen Corps national survey (summary sheet). Retrieved June 30, 2012, from http://citizencorps.gov/downloads/pdf/ready/2009_Citizen%20Corps_National%20Survey_Findings_SS.pdf

Franko, K. (2011, October 29). Ohio mock zombie outbreak inspired by CDC message. Associated Press.

Good, C. (2011, May 20). Why did the CDC develop a plan for a zombie apocalypse? The Atlantic. Retrieved June 19, 2012, from http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2011/05/why-did-the-cdc-develop-a-plan-for-a-zombie-apocalypse/239246

Greene, R. A. (2011, May 19). Ready for a zombie apocalypse? CDC has advice. CNN.com. Retrieved May 14, 2012, from http://www.cnn.com/2011/HEALTH/05/19/zombie.warning

Gross, D. (2009, October 2). Why we love those rotting, hungry, putrid zombies. CNN.com. Retrieved May 14, 2012, from http://www.cnn.com/2009/SHOWBIZ/10/02/zombie.love/index.html

Hassett, M. (2011, May 25). Zombies, space & social media success. CNN News Stream [Weblog]. Retrieved April 3, 2013, from http://newsstream.blogs.cnn.com/2011/05/25/zombies-space-social-media-success

Hibberd, J. (2013, October 14). “The Walking Dead” season 4 premiere ratings enormous. Entertainment Weekly Inside TV [Weblog]. Retrieved October 30, 2013, from http://insidetv.ew.com/2013/10/14/the-walking-dead-returns-to-record-viewership

Klinenberg, E. (2008, July 6). Are you ready for the next disaster? Why we’re so bad at preparing for catastrophe. New York Times, A15.

Li, S. (2011, May 21). Unprepared for a zombie attack? CDC offers tips; Agency hopes tongue‑in-cheek advice will inspire people to get ready for a real emergency. Los Angeles Times, B2.

Lupkin, S. (2012, September 7). Government zombie promos are spreading. ABC News Medical Unit [Weblog]. Retrieved September 9, 2012, from http://abcnews.go.com/blogs/health/2012/09/07/government-zombie-promos-are-spreading

Marsh, W. (2011, May 19). CDC ‘zombie apocalypse’ disaster campaign crashes website. Reuters. Retrieved October 31, 2013, from http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/05/19/us-zombies-idUSTRE74I7H420110519

McKay, B. (2011, May 18). CDC advises on zombie apocalypse … and other emergencies. Wall Street Journal Health [Weblog]. Retrieved May 14, 2012, from http://blogs.wsj.com/health/2011/05/18/cdc-advises-on-zombie-apocalypse-and-other-emergencies

Miami police shoot, kill man eating another man’s face. (2012, May 26). CBS4 Miami. Retrieved April 26, 2013, from http://miami.cbslocal.com/2012/05/26/miami-police-confrontation-men-leaves-1-dead-1-hurt

Miller, D. (2012, October 30). Why zombies rule. Huffington Post. Retrieved March 25, 2013, from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/dennis-miller/zombies-popular-culture_b_2022855.html

National Association of Government Communicators. (2012). 2012 blue pencil and gold screen awards. Retrieved April 22, 2013, from http://www.nagconline.org/Awards/documents/NAGCBPGSAwardsweb.pdf

National Geographic Channel. (2012). Doomsday preppers survey. Retrieved June 20, 2012, from http://images.nationalgeographic.com/wpf/media-live/file/Doomsday_Preppers_Survey_-_Topline_Results.pdf

Nelson, C., Lurie, N., Wasserman, J., & Zakowski, S. (2007). Conceptualizing and defining public health emergency preparedness. American Journal of Public Health, 97(S1), S9‑S11.

O’Reilly, B. (2011, May 20). Dumbest things of the week. The O’Reilly Factor.

PR News. (n.d.). Platinum PR awards 2011. Retrieved April 22, 2013, from http://www.prnewsonline.com/platinumpr2011

Praetorius, D. (2011, January 4). May 21, 2011: Judgment day rumors spread across the U.S. Huffington Post. Retrieved April 26, 2013, from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/01/04/may-21-2011-judgment-day_n_804166.html

Richardson, S. (2011, October 19). Centers for Disease Control brilliantly respond to the coming zombie pandemic. The Gazette [Colorado Springs, CO] Broadside [Weblog]. Retrieved June 19, 2012, from http://thebroadside.freedomblogging.com

Ross, E. (2011, September 29). When ‘zombies’ attack, the government wants you prepared. The Hutchinson News [KS].

Sandman, P. M. (2012, March). Motivating attention: Why people learn about risk … or anything else. Risk = Hazard + Outrage: The Peter Sandman Risk Communication Website. Retrieved May 28, 2013, from http://www.psandman.com/col/attention.htm

Solomon, J. D. (2008, May 18). Asleep at the switch: It’s an emergency. We’re not prepared. Washington Post, B1.

Stacks, D. W. (2011). Primer of public relations research (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Stacks, D. W., & Michaelson, D. (2010). A practitioner’s guide to public relations research, measurement, and evaluation. New York: Business Expert Press.

Stobbe, M. (2011, May 20). CDC ‘zombie apocalypse’ advice an Internet hit. Associated Press.

Suarez, K. D. (2011, May 20). Ready for a zombie apocalypse? CDC gives tips. ABS-CBN News. Retrieved April 22, 2013, from http://www.abs-cbnnews.com/lifestyle/05/20/11/ready-zombie-apocalypse-cdc-gives-tips

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010a, January 11). Vision, mission, core values, and pledge. Retrieved April 8, 2013, from http://www.cdc.gov/about/organization/mission.htm

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010b, February 25). CDC fact sheet. Retrieved April 8, 2013, from http://www.cdc.gov/about/resources/facts.htm

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011a, May 16). Preparedness 101: Zombie apocalypse. Public Health Matters [Weblog]. Retrieved May 14, 2012, from http://blogs.cdc.gov/publichealthmatters/2011/05/preparedness-101-zombie-apocalypse

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011b, May 26). First there were zombies; then came hurricanes! Public Health Matters [Weblog]. Retrieved April 8, 2013, from http://blogs.cdc.gov/publichealthmatters/2011/05/first-there-were-zombies-then-came-hurricanes

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011c, October 5). Q & A with Max Brooks. Public Health Matters [Weblog]. Retrieved April 8, 2013, from http://blogs.cdc.gov/publichealthmatters/2011/10/q-a-with-max-brooks

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011d, October 12). Dragon*Khan. Public Health Matters [Weblog]. Retrieved April 8, 2013, from http://blogs.cdc.gov/publichealthmatters/2011/10/dragonkhan

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011e, October). Preparedness 101: Zombie pandemic. Retrieved April 8, 2013, from: http://www.cdc.gov/phpr/documents/11_225700_A_Zombie_Final.pdf

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012a, May 18). Zombie nation: Teaching preparedness through a zombie outbreak. Public Health Matters [Weblog]. Retrieved April 8, 2013, from http://blogs.cdc.gov/publichealthmatters/2012/05/teaching-preparedness-through-a-zombie-outbreak

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012b, July 11). Executive leadership and expert bios. Ali S. Khan, MD, MPH. Retrieved April 8, 2013, from http://www.cdc.gov/media/subtopic/sme/khan.htm

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012c, September). Preparedness 101: Zombie pandemic [preparedness ideas for educators]. Retrieved April 8, 2013, from http://www.cdc.gov/phpr/learn.htm

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012d, November 14). Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response. Social media channels. Retrieved April 8, 2013, from http://www.cdc.gov/phpr/connect.htm

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2012, March 30). New HHSinnovates winners show culture of innovation at HHS. Retrieved April 22, 2013, from http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2012pres/03/20120330a.html

Veil, S. R., Littlefield, R. S., & Rowan, K. E. (2009). Dissemination as success: Local emergency management communication practices. Public Relations Review, 35, 449‑451.

Wasted time. (2011, May 26). Bladen Journal [Elizabethtown, NC]. Available online at http://www.bladenjournal.com

Weise, E. (2011a, May 19). CDC helps Americans prepare for a zombie apocalypse. USA Today Science Fair [Weblog]. Retrieved May 14, 2012, from http://content.usatoday.com/communities/sciencefair/post/2011/05/cdc-helps-americans-prepare-for-a-zombie-apocalypse/1

Weise, E. (2011b, October 19). Get ready for return of the CDC zombies! Agency deploys graphic novel in latest plot to teach families to brace for disaster. USA Today, 3A.

WGN-TV. (2011, May 20). News anchor not a fan of CDC’s “zombie blog” and she shows it [Video recording]. Retrieved June 22, 2012, from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AgpLOpUIV24

Zombies rise again in pop culture. (2011, October 21). CBS News. Retrieved June 19, 2012, from http://www.cbsnews.com/video/watch/?id=7385505n&tag=mncol;lst;5

MARJORIE KRUVAND, Ph.D., is an associate professor in the School of Communication at Loyola University Chicago. Email: mkruvand[at]luc.edu.

MAGGIE SILVER, MPH, CHES, is a health communication specialist in the Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Email: msilver[at]cdc.gov.

Editorial history

Received July 3, 2013

Revised October 30, 2013

Accepted October 30, 2013

Published October 31, 2013

Handled by editor; no conflicts of interest