To cite this article

Aylesworth-Spink, S. (2016). Protecting the herd: An analysis of public relations responses to the 2015 measles outbreak originating at Disneyland and Disney California Adventure Park. Case Studies in Strategic Communication, 5, article 10. Available online: http://cssc.uscannenberg.org/cases/v5/v5art10

Access the PDF version of this article

Protecting the Herd: An Analysis of Public Relations Responses to the 2015 Measles Outbreak Originating at Disneyland and Disney California Adventure Park

Shelley Aylesworth-Spink

University of West London

Abstract

This case study reviews the public relations response when Disneyland and Disney California Adventure Park were declared the epicenter of a North American measles outbreak in 2015. The case study highlights and analyzes public relations strategies and tactics by the state public health department and The Walt Disney Company under the backdrop of the amorphous yet growing anti-vaccine movement. Centered on the surprising yet predictable 21st century resurgence of measles in North America, this case highlights the positioning of a health crisis by a corporation with an iconic entertainment brand and the challenge of public communications by a public health department during a disease outbreak. As the outbreak unfolded, public health communicators faced the two-pronged problem of refuting the claims of anti-vaccination advocates just as they dealt with population health risks. The public relations actions by organizations involved helped them emerge relatively unaffected by the crisis. This case is ideal for communications students studying crisis communications and public relations campaigns involving messy societal issues and the varied interests of multiple actors.

Keywords: public communications; Disney; crisis communications; reputation management; vaccination; anti-vaccination; measles; disease outbreak; public health promotion

Introduction

Measles was declared conquered by the United States in 2000 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2015). Up until a few years ago, most practicing physicians across North America had never treated a case of measles.

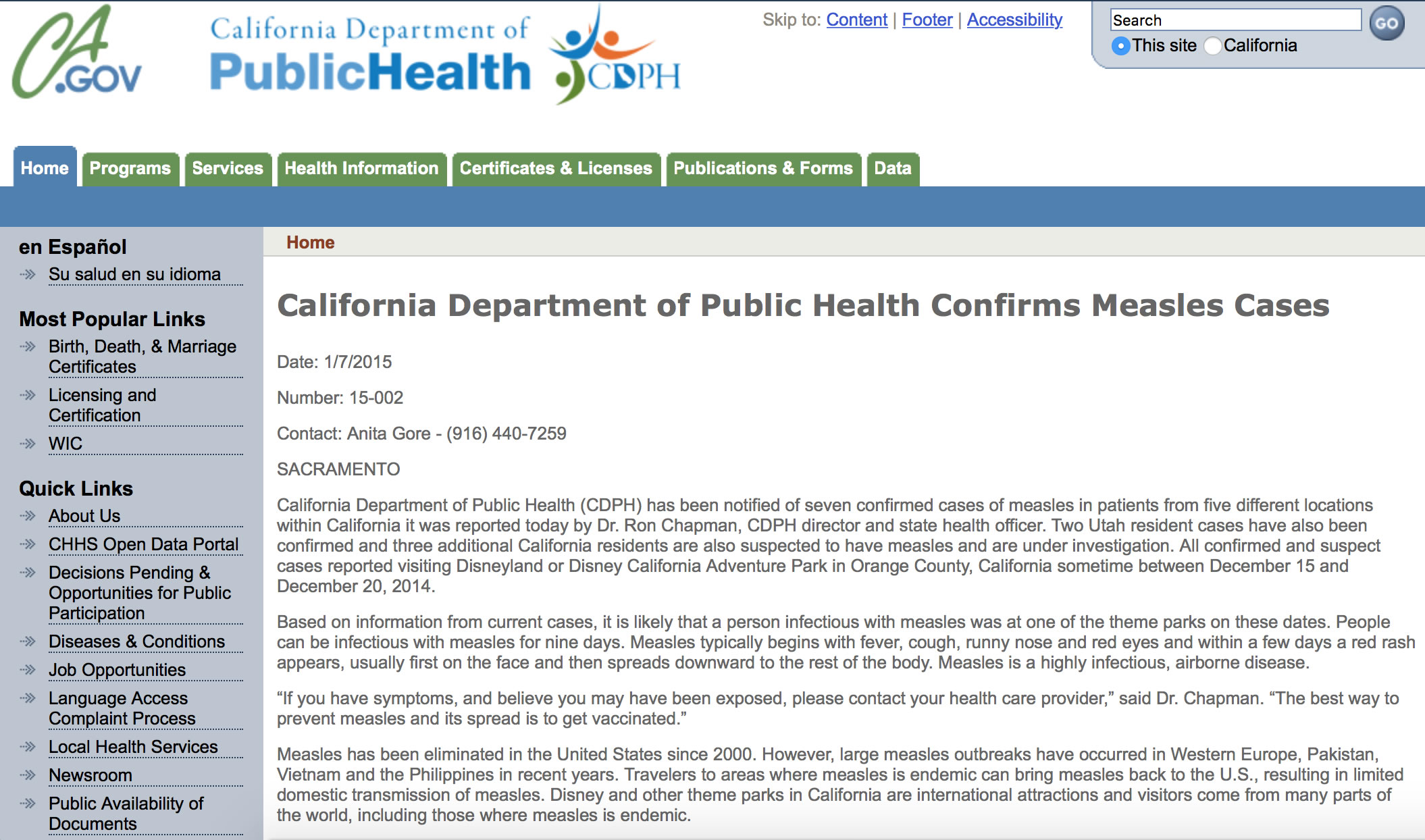

Yet, on January 7, 2015, the California Department of Public Health issued a media release confirming seven cases of measles in people from five different locations in California (“California Department of Public Health Confirms Measles Cases,” 2015). All reported visiting Disneyland or Disney California Adventure Park in Orange County sometime over the 2014 holiday period. Six of these seven people infected were unvaccinated for measles. Not only had a dreaded and highly contagious disease made a comeback, but it re-appeared in a densely populated state at properties owned and operated by a global entertainment icon: The Walt Disney Company.

The outbreak was officially declared over on April 15, 2015, but not before it had infected 111 people from across seven states, Mexico, and Canada (Clemmons, Gastanaduy, Fiebelkorn, Redd, & Wallace, 2015).

Largely considered a disease overcome in the western world through a regime of childhood vaccination that began in the 1960s, this high profile resurgence of the measles appeared surprising. Yet, to many public health experts, a widespread measles outbreak seemed inevitable owing to the influence of an anti-vaccination movement sprinkled across North America and most specifically in southern California. As noted by the CDC (2014a), measles outbreaks such as this reveal pockets of unvaccinated people in some communities across the U.S.

Organizations central to this case study were those involved and implicated in the public relations response during the 2015 measles outbreak: the California Department of Public Health (CDPH), The Walt Disney Company, and the amorphous anti-vaccine movement. Public relations strategies and tactics by the CDPH and Disney are reviewed in light of these strategies, as is social media and news coverage throughout the four-month outbreak.

Through a review of news coverage, official statements by Disney and the CDPH, and legislative action in the wake of the outbreak, this case finds that Disney’s bottom line was unaffected by the crisis, and public health safeguards against measles were not only upheld but strengthened.

Given this defined period of time, the intricacies of public health communications, and the number and variety of interests and stakeholders involved, this case study is an ideal opportunity to study the connected public relations issues of crisis communications, reputation management, and broad public communications. This case also raises questions about how public relations professionals can effectively communicate with the public during a health outbreak even as they face ongoing needs to convince the public to take proactive public health measures such as following the recommend regime of childhood immunization.

Additionally, the complexity of this case highlights the importance of cross-sectorial relationships between public relations professionals in government agencies, such as health departments, and in the private sector, like Disney. The smooth functioning interdependence of the public and private sectors in this case was made more urgent because of the risks to the population’s health from a highly contagious disease.

Background

Measles: The Return of a Familiar Scourge

Measles is an ancient disease. In the 9th century, a Persian doctor published one of the first written accounts of measles (CDC, 2014b). In 1757, a Scottish physician demonstrated that measles is caused by an infectious agent in the blood.

In 1912, measles became a nationally notifiable disease in the United States, requiring healthcare providers and laboratories to report all diagnosed cases. In the first decade of reporting, an average of 6,000 measles-related deaths were reported each year. In the 10 years before the vaccine became available in 1963, nearly all children got measles by the time they were 15 years of age. It is estimated 3 to 4 million people in the U.S. were infected each year, 400 to 500 people died, 48,000 were hospitalized, and 4,000 suffered encephalitis from measles (World Health Organization [WHO], 2016).

Measles is a highly contagious viral disease that remains an important cause of death among young children around the world (WHO, 2016). The disease moves through populations from the nose, mouth, or throat of those infected. Symptoms begin with high fever, a runny nose, bloodshot eyes, and tiny white spots on the inside of the mouth followed by a rash that spreads to cover the body. Serious complications can develop from the measles, notes the WHO, including blindness, encephalitis (an infection that causes brain swelling), severe diarrhea, and life-threatening respiratory infections such as pneumonia.

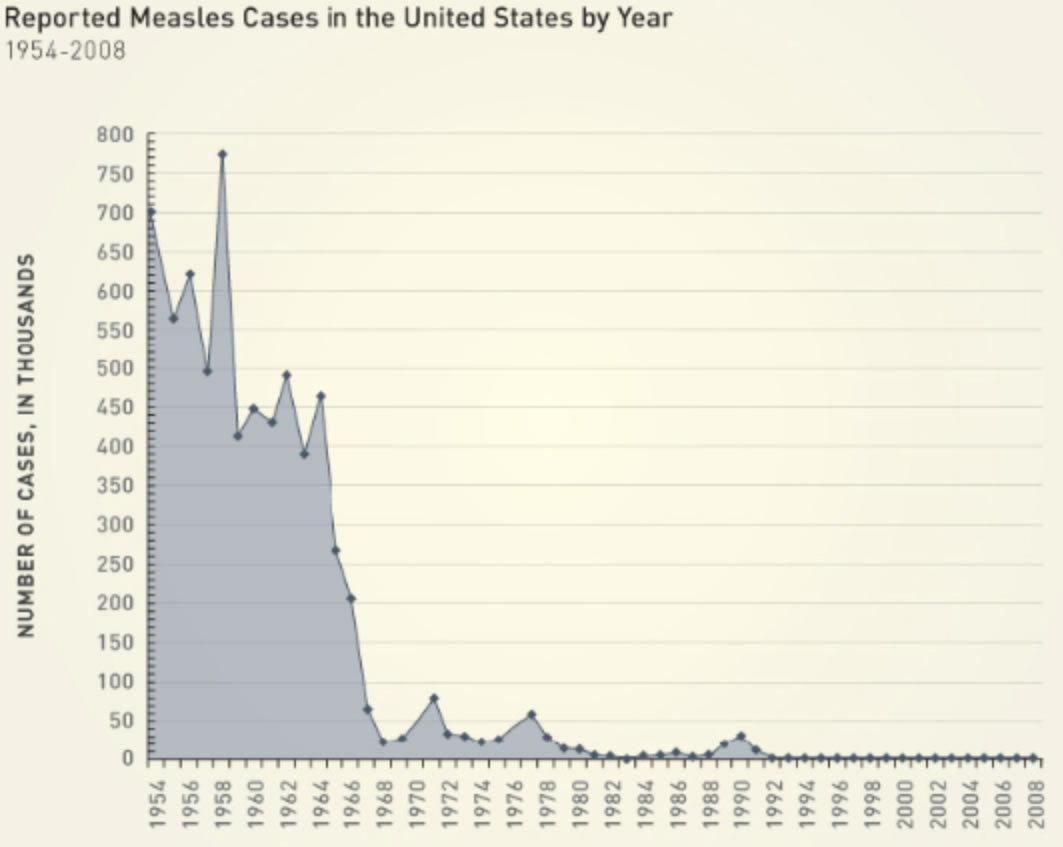

It seems peculiar that a widespread disease with known antidotes would occur on a large scale in developed nations. As Figure 1 shows, the discovery of a measles vaccine in 1963 dramatically decreased the number of measles victims in the U.S.

Figure 1. Reduction in measles cases in the U.S. following vaccine discovery (Source: CDC/MMWR Summary of Notifiable Diseases, United States, 1993; CDC/MMWR Summary of Notifiable Diseases, United States, 2008).Yet, in 2014, measles made a comeback in the U.S. with 23 outbreaks, including one large spate of 383 cases among unvaccinated Amish communities in Ohio (CDC, 2016). Many of the 2014 cases linked to those that came from the Philippines, a country that experienced a large measles outbreak.

The 2014 measles outbreak was not yet over. The same measles virus type that reared its head in the Philippines returned to the United States the following year. On January 5, 2015, the CDPH discovered a suspected measles case: a hospitalized and unvaccinated 11-year-old with a rash that began in late December (Zipprich, Winter, Hacker, Xia, Watt, & Harriman, 2015). Notably, the child’s only recent travel was a visit to one of two neighboring Disney theme parks located in Orange County, California. On the same day, the public health department received reports of four additional suspected measles cases in California residents and two in Utah residents, all of whom reported visiting one or both Disney theme parks during December 17-20. By January 7, seven California measles cases had been confirmed, and CDPH issued a press release and notified other states.

A lack of immunization was quickly named as the leading cause of the outbreak, a reality that hit home when the crisis was declared over. In the end, officials found that among the California patients, 45% were unvaccinated, others had from one to three doses of a measles-containing vaccine, and 43% had unknown or undocumented vaccination (Clemmons et al., 2015). Twelve of the unvaccinated patients were infants too young to be vaccinated. Among the vaccine-eligible patients, 67% were intentionally unvaccinated because of personal beliefs. Those infected ranged in age from six weeks to 70 years old. Twenty percent of those infected during this outbreak were hospitalized.

The California Department of Public Health

The CDPH operates under the State of California—the most populous state in the U.S.—with a mission to optimize the health and wellbeing of its 38 million residents. The department’s strategy from 2014 to 2017 centers on three priorities: to strengthen as an organization, communicate and promote the value of public health, and prevent and control disease and injury (California Department of Public Health [CDPH], 2015e).

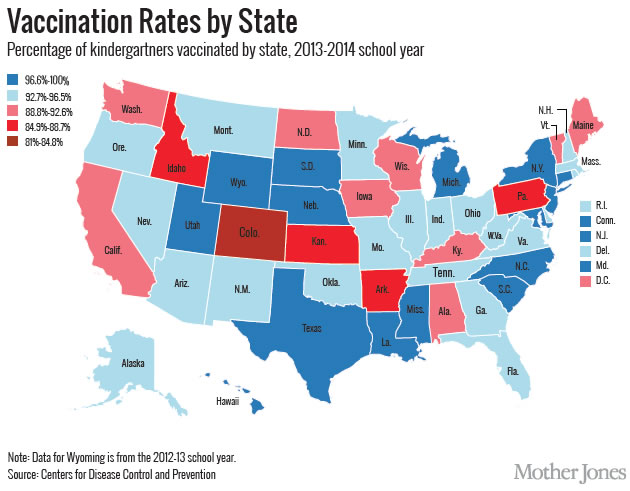

Despite the fact that vaccination is a top public health achievement of the 20th century, public health officials and the rest of the medical community continue to struggle with public compliance. For example, childhood immunization rates across the U.S. declined from 92.1% in 2008 to 90.8% in 2012 (CDC, 2013). As Figure 2 shows, California has among the lowest vaccine rates among kindergartners (Seither et al., 2014).

Figure 2. Vaccination rates by state, 2013-14 school year (Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).As the measles outbreak raged in 2015, the State of California continued to struggle with low vaccination coverage mainly owing a “personal belief” exemption law. Parents could exempt their child from vaccination if they had proof from their physician that they had received information about vaccine-preventable illnesses and the benefits and risks of immunization. Rates of personal belief exemptions in California have doubled since 2007 (CDPH, 2016), and analysts note that vaccination coverage is low enough to jeopardize herd immunity[1] in a quarter of schools (Bloch, Keller, & Park, 2015). However, even as the state worked to introduce new legislation that would only allow children to skip vaccination on medical grounds, some parents stood in fierce opposition.

Poor immunization uptake happens for various reasons. These include distrust among parents in industry, government, and doctors; uncertainty about vaccine safety; a rapid increase in the number of vaccines; increasing cases of autism; and the rise of the anti-vaccine movement online and among some celebrities (Sawyer, 2015).

The Anti-Vaccination Movement

A chief catalyst for the anti-vaccination movement was a 1998 article by Andrew Jeremy Wakefield, a former British surgeon and medical researcher, published in one of the world’s oldest and best-known medical journals, The Lancet. The article claimed a link between the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine and autism and bowel disease (Godlee, Smith, & Marcovitch, 2011). A vaccine scare took off, yet critics were quickly concerned that the study had few participants, no controls, and relied on anecdotal information and beliefs from parents. The paper was retracted 12 years later following a series of studies that found no evidence of a link between the vaccine and autism.

However, the study firmly planted the roots of a growing yet loosely organized anti-vaccine subculture. The movement involves dozens of online support groups, social media sites, conferences, and forums that oppose vaccination as harmful, the source of injury, and motivated by pharmaceutical business interests. A sample of websites include www.vaccine-injury.info, about the damage to children from vaccinations; www.thehealthyhomeeconomist.com, listing six reasons to say “no” to vaccination; and www.livingwhole.org that outlines why God does not support vaccines.

Public relations practitioners should understand the anti-vaccine movement as a phenomenon. Members of this subculture value their individual freedom and believe that they are acting responsibly to protect their children against incorrect societal norms. In Orange County—wealthy and well educated—some parents have opted out of having their children vaccinated at a rate far above the state average (Foxhall, 2015b). In some Los Angeles schools, immunization rates are lower than parts of South Sudan (Khazan, 2014).

The most famous fuel for the anti-vaccine movement is American actress Jenny McCarthy. She has appeared on dozens of talk shows, at events, and in media reports describing the effects of childhood immunization on her son whom she said contracted autism from being immunized as an infant. In fall 2013, shortly after joining the cast of the television talk show The View, she faced outrage because of her widely documented opinion against vaccination and use of a public platform to “potentially share those thoughts” (Yahr, 2014, para. 6). McCarthy’s greatest opposition to vaccines are their ingredients, which she believes cause injury to children.

Flash forward to 2015, and the return of the measles revived the anti-vaccine sentiments in North America that lurked just below the surface. Its advocates had made slow gains on convincing parents to question and reject regimes of childhood immunization. The measles outbreak that began in California and most prominently spread from Disneyland ignited a broader vaccination debate with the anti-vaccination movement at its forefront. This discussion has been “a wake-up call for many doctors and scientists who work on the front lines of infectious disease outbreaks. They have watched with growing unease as the anti-vaccination movement has gained voice” (Parker 2015, para. 5).

Disneyland and Disney California Adventure Park

The Disneyland theme park resort and Disney California Adventure Park are owned by The Walt Disney Corporation. Disney is a diversified international family entertainment and media enterprise with the following business segments: media networks, parks and resorts, studio entertainment, consumer products, and interactive media (The Walt Disney Company, 2016a). The company, as noted on the Disney corporate website, operates worldwide in more than 40 countries and employs about 166,000.

In 1955, Disney opened Disneyland as its first amusement park. The park began a pattern for every Disney amusement park built since then (The Walt Disney Company, 2016b). Disney California Adventure opened in 2001 and focuses on the history, culture, and spirit of California.

Annual attendance at Disney theme parks in California is estimated at 24 million (Themed Entertainment Association, 2015), including many international visitors from countries where measles is endemic.

Strategy and Timeline of Public Relations Tactics

Public relations strategies and tactics by the CDPH and The Walt Disney Corporation differed considerably. The health department adopted a high profile, proactive stance while Disney’s response was muted and low profile.

As an amorphous movement, those who do not believe in vaccination had no central public relations response or strategy. Many media reports, in attempts to balance coverage, included comments from parents who are part of the movement. For example, one mother in a CBS This Morning report said her son suffered an allergic reaction to immunization, and she encouraged parents to get more information before vaccinating their children (CBS This Morning, 2015).

The strategy for the CDPH revolved around updates about the spread of the disease. The department centralized its spokespeople with public health leadership. Other medical experts, notably those from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; the U.S. public health agency), commented in media reports across the state and country. As with all medical spokespeople, the CDPH upheld consistent messaging centered on two elements: the march of the outbreak across the U.S. and the necessity of immunization.

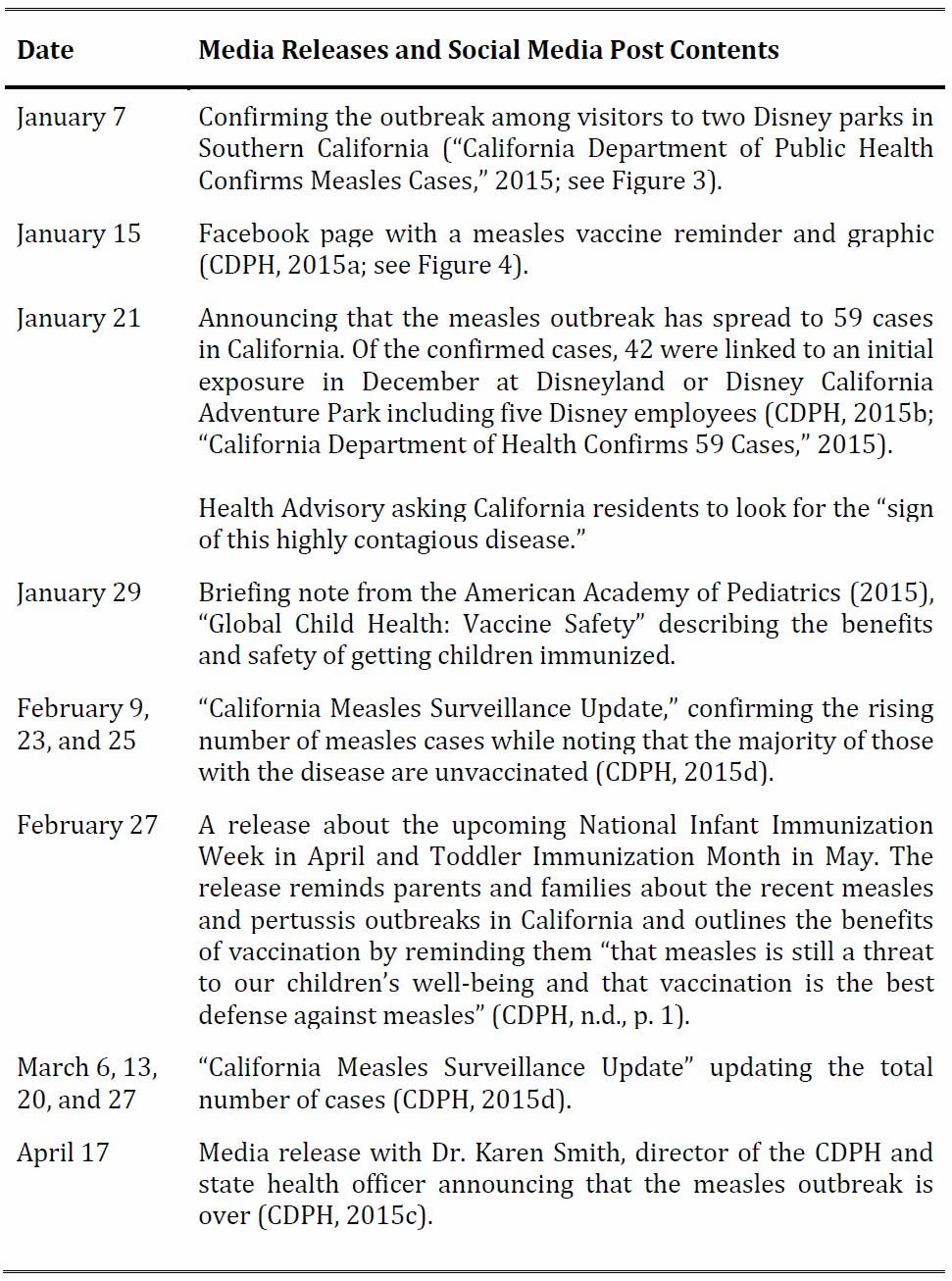

CDPH gave frequent, sometimes daily, updates on its website and in media releases about the number of measles cases, whether those people were immunized, and the location of new cases. Each release highlighted immunization as the best protection from measles and where the public could access vaccines. Table 1 lists the department’s media releases and social media posts from January to April 2015.

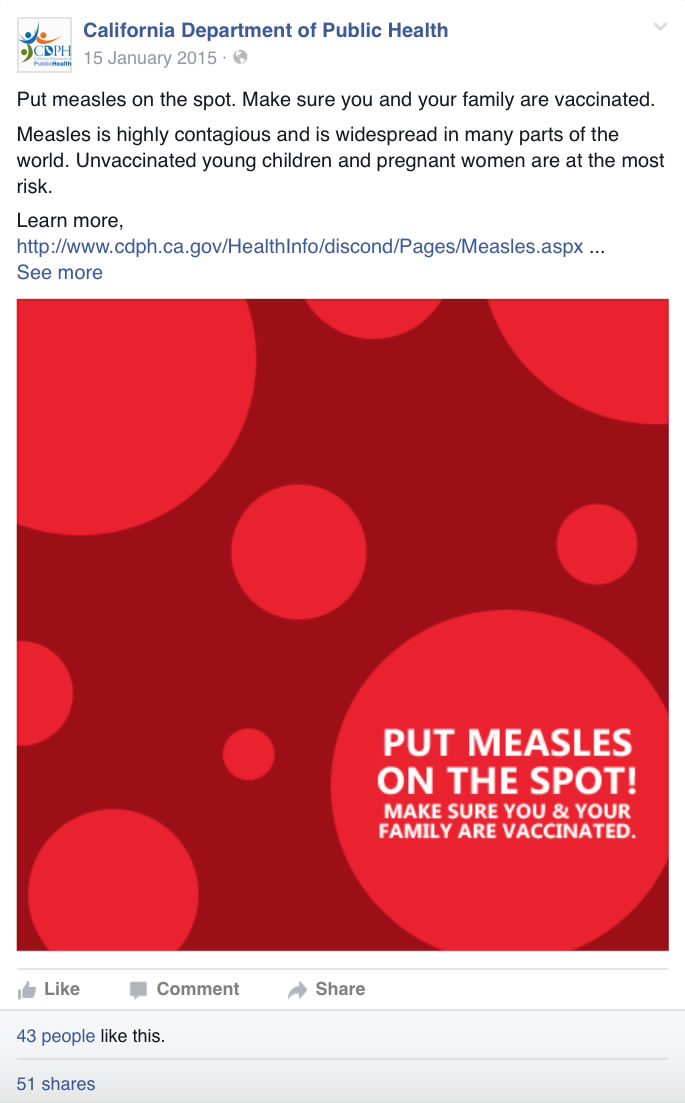

Table 1. CDPH media releases and social media posts January-April 2015. Figure 3. January 7, 2015, CDPH press release confirming measles cases. Figure 4. CDPH Facebook post on January 15, 2015.The constant flow of information from CDPH to the media started a deluge of media attention to the Disney parks as the geographic center of the outbreak. Initial media stories in particular prominently referenced Disney, with some reports calling the incident the “Disneyland measles outbreak” (CBS This Morning, 2015).

For Disney, its public relations strategy was to align ownership and authority of the outbreak’s management with the state public health department and the broader medical community. None of the Disney official public communications channels contained regular, updated information about the status of the outbreak. Disney participated in media interviews through statements that were brief and supportive of the medical community’s need to manage the outbreak. The day that the outbreak was announced by the CDPH, Walt Disney Parks and Resorts issued a statement from its chief medical officer, Dr. Pamela Hymel, picked up by dozens of media outlets, that “we are working with the health department to provide any information and assistance we can” (Foxhall, 2015a, para. 6).

As a giant in the entertainment industry, Disney commands a vast array of communications channels yet virtually none were used to communicate during the outbreak. Rather, the company’s websites, social media channels, and media products continued to send messages that firmly align with the company mission and values:

to be one of the world’s leading producers and providers of entertainment and information. Using our portfolio of brands to differentiate our content, services and consumer products, we seek to develop the most creative, innovative and profitable entertainment experiences and related products in the world. (The Walt Disney Company, 2016a, para. 1)

Disney’s participation in social media is extensive and enormous. All channels sustain high levels of engagement with an increasing army of fans and followers. On the corporate @Disney Twitter feed, with 4.7 million followers as of February 2016, its social media managers post or retweet at least two to three times each day and often include high quality and Disney archival video and photos themed on events and seasons (see Figure 5 for a sample). Each of its signature properties has a Twitter handle, including @Disneyland (more than 900,000 followers); @WaltDisneyWorld (more than 2.1 million followers); and @DisneylandToday, the Twitter feed for Disneyland, Disney California Adventure Park, Downtown Disney, and resort hotels (more than 370,000 followers).

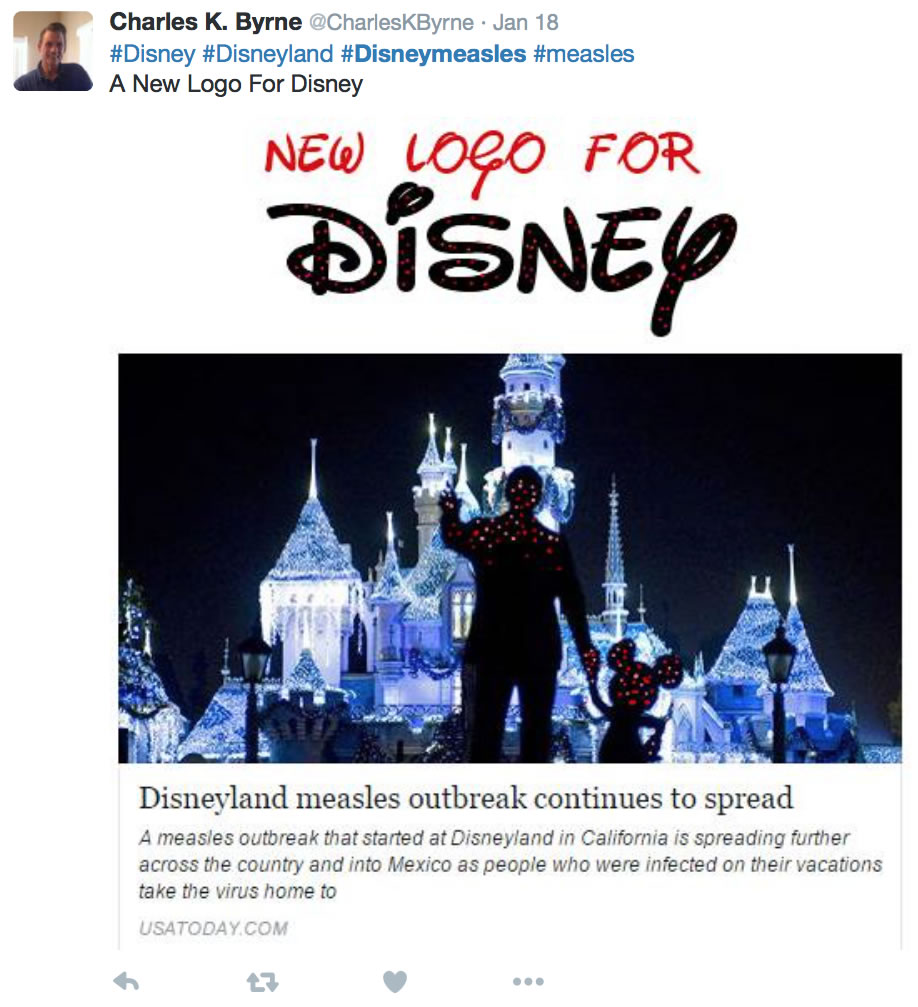

Figure 5. @Disney sample Twitter homepage.Despite the Disney public relations strategy of not including frequent information about the outbreak on its official channels, general social media response to the announced outbreak was swift. The hashtag #disneymeasles launched on January 8 (see Figure 6), the same day that the CDPH announced the parks as sources of the outbreak. From the outset, iconic Disney characters were co-opted by social media users sharing altered photos and using the hashtag #disneymeasles to link the company’s brand to the outbreak (see Figures 7, 8, and 9). In some social media posts, the names of Disney rides were parodied: It’s a Smallpox World, Rash Mountain, and Big Thunder Mountain Rabies (parodying the It’s a Small World, Space Mountain, and Big Thunder Mountain rides, respectively).

Figure 6. The appearance of the hashtag #disneymeasles, January 8, 2015. Figure 7. Memes of co-opted Disney characters emerge with the hashtag #disneymeasles, January 13, 2015. Figure 8. An altered Disney photo with the hashtag #disneymeasles, January 18, 2015. Figure 9. Another altered photo of a Disney character with the hashtag #disneymeasles, February 1, 2015.Through media statements, Disney made it clear that its employees were also affected by the outbreak. The company noted, in a January 22 CNN story, that after Orange County health officials contact them on January 7, “we immediately began to communicate to our cast [employees] to raise awareness,” and that

in an abundance of caution, we also offered vaccinations and immunity tests. To date, a few Cast Members [employees] have tested positive and some have been medically cleared and returned to work. Cast Members who may have come in contact with those who were positive are being tested for the virus. While awaiting results, they have been put on paid leave until medically cleared. (Berlinger, Levs, & Hamasaki, 2015, para. 10-11)

Less than a week later, in a January 28 CNN story, Disney spokesperson Suzi Brown connected the value of immunization with safe amusement parks: “We agree with Dr. [Gil] Chavez’s [deputy director of the California Center for Infectious Diseases] comments that it is safe to visit Disneyland if you have been vaccinated” (Ellis, 2015, para. 10).

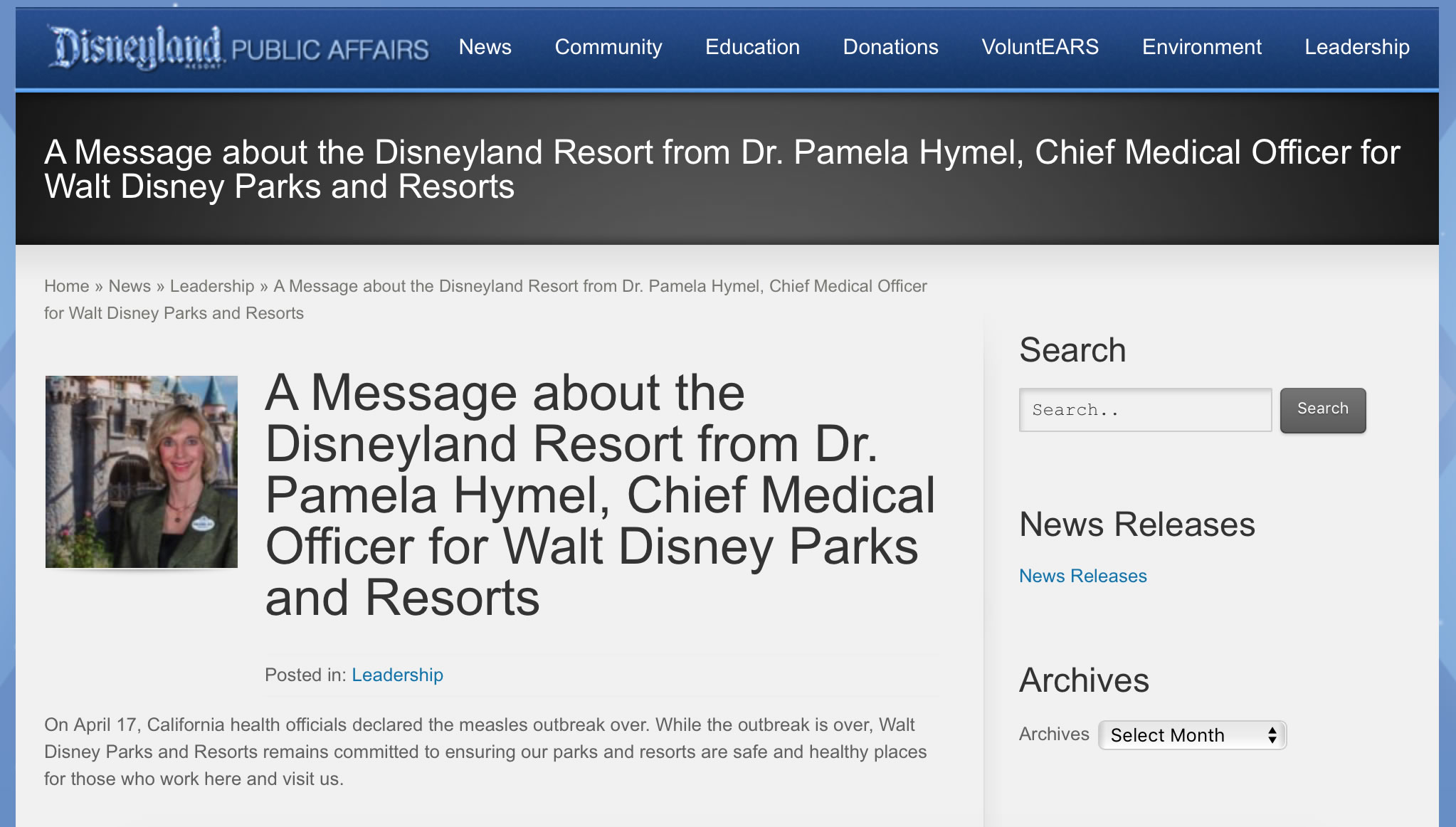

When the CDPH announced that the outbreak was over on April 17, 2015, Disney Public Affairs continued to follow its message strategy, responding with a statement from the chief medical officer affirming the end of the outbreak and the company’s commitment to safety at its locations (see Figures 10 and 11). Finally, from its website, Disney Public Affairs pointed to a Q&A with Dr. Hymel on the CDC Foundation website outlining the company’s approach to the outbreak (CDC Foundation, 2015). Disneyland also posted a response to a frequently asked question, “What’s the latest update on the measles outbreak in Orange County, California?,” by pointing to the statement about the end of the outbreak from Dr. Hymel (The Walt Disney Company, 2015).

Figure 10. Disneyland Public Affairs webpage about the declared end of the measles outbreak, April 17, 2015. Figure 11. Disney Help Center FAQ webpage linking to the Disney Public Affairs page declaring the end of the measles outbreak.Evaluation

The two organizations centrally involved in this case, the CDPH (and by extension, the State of California) and The Walt Disney Corporation, each linked their public relations activities during the measles outbreak to suit their organization’s respective needs and objectives. Public relations strategies were successful for both Disney and the CDPH.

New Vaccination Legislation for California

The strategy by the CDPH of providing constant updates on the numbers of infected owing to them not being vaccinated was a constant reminder of the need for immunization. This strategy also debunked anti-vaccine claims in media coverage and on social media. For example, social media comments on #disneymeasles by anti-vaccine supporters were quickly refuted by vaccine advocates who used the reported spread of the disease as evidence. Additionally, the mass media had consistently new information about the number of infected members of the population which kept the story alive throughout the four-month outbreak.

California health officials were successful on a much larger front as well. The outbreak highlighted its lack of legislative power in light of the state’s personal exemption law. In just a few short weeks as the measles outbreak raged, the public came face to face with the reality of measles and the consequence of a lack of herd immunity. On June 25, 2015, just two months after the measles outbreak was declared over, California signed into law a bill that substantially narrows exceptions to school-entry vaccination (Mello, Studdert, & Parmet, 2015). California had become the third state to disallow exemptions based on both religious and philosophical beliefs; only medical exemptions remain. The new law prohibits schools from unconditionally admitting children who are not up to date on vaccinations against a prescribed list of diseases unless they have a medical exemption.

Business Unaffected at Disney

The Disney public relations strategy played out throughout the outbreak period, and despite two of their entertainment properties initially being at the center of the media storm, their business results were unaffected. For example, in a February 3, 2015, interview with Bloomberg Business, Disney Chairman and CEO Bob Iger communicated the following messages: that the company takes the outbreak very seriously, that the outbreak was not impacting their business, and that, instead, the company was ahead in its advanced bookings and attendance when compared with the previous year (“Disney Theme Park,” 2015).

The success of the public relations strategy also paved the way for Disney, near the end of February 2015, to raise ticket prices to attend Disneyland, Walt Disney World, and the rest of its U.S. theme parks (Pimentel, 2015). At the two parks where the outbreak began, a one-day ticket rose to $99 for those aged 10 and older, up from $96.

Analysis and Discussion

This case study illustrates how during the same crisis, different organizations can employ contrasting public relations strategies yet still meet their respective goals. It also shows the complexities of some issues when multiple players are involved, particularly those relating to health risks. Ironically, the location of the epicenter of the outbreak—at properties owned by a global entertainment powerhouse—sent a strong, high-profile message to the public that the measles can happen to anyone at any time because of spotty vaccination across the population.

The issue of anti-vaccination had clearly been growing for years leading up to this outbreak. However, the public relations actions by the CDPH solidified its messages about the fast spread of the disease and the vigilance needed by the public about routine immunizations. Its relentless media release strategy sent a clear message in two ways: that public health officials were concerned enough to update the public, often daily, about the growing numbers of those infected, and that measles is spreading, so families must get immunized.

Disney’s actions helped the company emerge relatively unaffected by the crisis. The company response was to position itself as not centrally involved in the issue while communicating its cooperation with officials about a matter of public safety. Their public relations activities allowed them to be seen as turning to public health experts. Disney appropriately sustained its ongoing communications strategies and tactics supporting its overall brand in the entertainment industry to its customers and shareholders.

The online response quickly connected a lack of vaccine to the outbreak, detaching Disney from culpability and instead linking the company to a collective effort to boost immunization in the face of a threat that knows no geographic or corporate boundaries. Disney’s message strategy allowed the company to distance its entertainment properties from the outbreak and the associated negative profile of a public health outbreak.

Disney limited its media involvement during the outbreak by focusing its few statements on the company’s cooperation with public health experts. None of the Disney sites or social media channels contained reference to the outbreak at Disneyland. Similarly, no official comments came from the company to refute opinions voiced online or in the mass media.

Further to this strategy of detaching the issue from the brand, on the Disneyland official website, frequently asked questions about the outbreak appeared under “theme parks” in the Help Center section. Web visitors were directed to the corporate section of the site, under Disneyland Public Affairs, for more information and statements from the park’s medical officer.

Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) helps explain the success of the public relations actions by both Disney and the CDPH. SCCT maps critical variables that shape attributions of crisis responsibility (Coombs, 2015). Following this attribution process, Disney minimally claimed responsibility for the outbreak and was thus positioned as a victim of the crisis. The CDPH, on the other hand, assumed a different crisis frame that produced strong attributions of organizational responsibility.

In an interesting twist, Disney was the subject of a New York Times article that highlighted Disney’s firm control on public communications to “pull back the curtain on what can be a delicate process” (“In Emails,” 2015, para. 3). The article said that Disneyland officials expressed concern to health leaders about potential harm to Disney theme parks from the negative profile of the measles outbreak. They requested that Disney messages be part of the health department’s public communications. For example, in one email exchange highlighted in the news story, Disneyland’s chief medical officer, Dr. Pamela Hymel, forwarded to California’s top epidemiologist, Dr. Gil Chavez, a statement from Disneyland’s public relations arm with “some points,” including: “It is absolutely safe to visit these places, including the Disneyland Resort, if you are vaccinated” (“In Emails,” 2015, para. 17).

The story also shared email communications from Disneyland’s VP of communications, Cathi Killian, to the state health agency, laying out the company’s request that the public be advised measles was highly contagious and could be prevented only through vaccination.

“Basically, our goal is to ensure people know that the exposure period at the Disneyland Resort is now over, that this has nothing to do with Disneyland and this could happen anywhere,” Ms. Killian wrote. She added: “Can you please let us know if you are able to help us on this front?” (“In Emails,” 2015, para. 13)

However, despite the potential problems of a news story revealing public relations strategies, Disney’s business was unaffected by the outbreak. Its attendance figures during and after the outbreak remained strong and the company increased ticket prices even as the numbers of people infected with measles rose.

The public relations actions by Disney and the CDPH also relate broadly to both the Page Principles for the effective practice of public relations and the Barcelona Principles 2.0 for the measurement and evaluation of public relations programs. In particular, both Disney and the CDPH followed the Page Principle of telling the truth when both organizations communicated the scale and scope of the outbreak in a timely and frequent manner (Arthur W. Page Society, n.d.). Disney and the CDPH also followed the third principle of the Barcelona Principles 2.0 by linking their communications efforts to effects on organizational results (International Association for the Measurement and Evaluation of Communication, 2015).

The anti-vaccination movement continues unabated. The passage of the tighter personal exemption law in 2015 faced vocal opposition that generated enormous media coverage, including from the California Coalition for Vaccine Choice, who note on their website that this law “eliminates a parent’s right to exempt their children from one, some, or all vaccines, a risk-laden medical procedure including death” (California Coalition for Vaccine Choice, 2015; see Figure 12). A New York Times article included comments from vaccine opponents such as Christina Hildebrand, the founder of A Voice for Choice, who said that “parental freedom is being taken away by this because the fear of contagion is trumping it” (Medina, 2015, para. 22). Questions about the safety of childhood vaccinations continue in a debate that highlights the balance between personal freedom and common good.

Figure 12. The California Coalition for Vaccine Choice homepage.Discussion Questions

- If you led public relations for a public health organization, how would you refute claims of well-educated, often wealthy and outspoken people who are part a movement against vaccination?

- As a public relations professional, how would you prepare spokespeople working in public health when asked about the sensitive topic of parents who refuse to vaccinate their children?

- How would you tackle the problem of sustaining public relations activities around a constant public communications campaign about routine immunization? What measures of success in your communications would you establish to monitor the effect of your public relations efforts?

- How did the public relations strategy by the CDPH support the legislative change about personal belief exemptions from vaccination?

- Comments on social media after Disneyland became the known source of the measles were sometimes negative about the company’s brand. How would you track sentiment towards your organization in the face of such negativity and plan your communications to ensure your brand is not damaged and your business results are unaffected?

- Disney did not engage its vast social media properties in communications about the outbreak. Did they make the right decision? What are your thoughts about the strategy of continuing to promote the brand experience in the face of negative profile in mainstream media and social media connecting the brand to a health outbreak?

Note

[1] Herd immunity describes “protection occurring when so many people in a region are immune to an infectious disease that it can’t spread to others” (“Herd Immunity,” 2011).

References

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2015, January). Global child health: Vaccine safety. Retrieved from https://www2.aap.org/international/immunization/pdf/IssueBrief_VaccineSafety_Jan2015.pdf

Arthur W. Page Society. (n.d.). The Page principles. Retrieved from http://www.awpagesociety.com/site/the-page-principles

Berlinger, J., Levs, J., & Hamasaki, S. (2015, January 22). 5 Disneyland employees diagnosed with measles. CNN. Retrieved from http://edition.cnn.com/2015/01/20/health/disneyland-measles/index.html

Bloch M., Keller J., & Park, H. (2015, February 6). Vaccination rates for every kindergarten in California. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/02/06/us/california-measles-vaccines-map.html

California Coalition for Vaccine Choice. (2015). California Coalition for Vaccine Choice. Retrieved from http://www.sb277.org

California Department of Public Health. (n.d.). National Infant Immunization Week [Email blast]. Retrieved from https://www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/immunize/Documents/NIIWTIM2015TdapFAQ.docx

California Department of Public Health. (2015a, January 15). Put measles on the spot. Make sure you and your family are vaccinated [Facebook status update]. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/CAPublicHealth/photos/a.100975002581.92354.94999047581/10152684664127582

California Department of Public Health. (2015b, January 21). Dr. Ron Chapman, director of the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) and state health officer, announced today that local public health officials have confirmed a total of 59 cases of measles in California residents since the end of December 2014 [Facebook status update]. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/CAPublicHealth/posts/10152696358367582

California Department of Public Health. (2015c, April 17). Measles outbreak that began in December now over. Retrieved from https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Pages/NR15-029.aspx

California Department of Public Health. (2015d, April 17). Measles surveillance updates. Retrieved from https://www.cdph.ca.gov/HEALTHINFO/DISCOND/Pages/MeaslesSurveillanceUpdates.aspx

California Department of Public Health. (2015e, May 7). California Department of Public Health strategic map 2014-2017. Retrieved from http://www.cdph.ca.gov/Documents/CDPH_Strategic_Map.pdf

California Department of Public Health. (2016). Immunization rates in child care and schools. Retrieved from http://www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/immunize/pages/immunizationlevels.aspx

California Department of Public Health confirms measles cases [Press release]. (2015, January 7). California Department of Public Health. Retrieved from http://www.cdph.ca.gov/Pages/NR15-002.aspx

California Department of Public Health confirms 59 cases of measles [Press release]. (2015, January 21). California Department of Public Health. Retrieved from http://www.cdph.ca.gov/Pages/NR15-008.aspx

CBS This Morning. (2015, January 14). Disney measles outbreak highlights anti-vaccine movement [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hV_2FAFD96o

CDC Foundation. (2015). Q&A with Walt Disney Parks and Resorts Dr. Pamela Hymel. Retrieved from http://www.cdcfoundation.org/businesspulse/workplace-safety-health-Q-A-Hymel

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013, September 13). National, state, and local area vaccination coverage among children aged 19-35 months – United States, 2012. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 62(36), 733-740. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6236a1.htm?s_cid=mm6236a1_w

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014a, September 2). Childhood immunization coverage infographic: Infant vaccination rates high, unvaccinated still vulnerable. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/nis/child/infographic-2013.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014b, November 3). Measles history. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/measles/about/history.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015, October 19). Frequently asked questions about measles in the U.S. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/measles/about/faqs.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, August 23). Measles cases and outbreaks. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/measles/cases-outbreaks.html

Clemmons, N. S., Gastanaduy, P. A., Fiebelkorn, A. P., Redd, S. B., & Wallace, G. S. (2015, April 17). Measles – United States, January 4-April 2, 2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 64(14), 373-376. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6414a1.htm

Coombs, W. T. (2015). The value of communication during a crisis: Insights from strategic communication research. Business Horizons, 58(2), 141-148.

Disney theme park attendance not hurt by measles: Iger [Video file]. (2015, February 3). Bloomberg Business. Retrieved from http://www.bloomberg.com/news/videos/2015-02-03/disney-theme-park-attendance-not-hurt-by-measles-iger

Ellis, R. (2015, January 28). Number of measles cases growing, California says. CNN. Retrieved from http://edition.cnn.com/2015/01/27/health/california-measles-outbreak

Foxhall, E. (2015a, January 7). Health alert after Disneyland linked to measles outbreak. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from http://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-measles-cases-tied-to-disneyland-california-adventure-20150107-story.html

Foxhall, E. (2015b, January 25). Parents who oppose measles vaccine hold firm to their beliefs. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from http://www.latimes.com/local/california/la-me-measles-oc-20150126-story.html

Godlee, F., Smith, J., & Marcovitch, H. (2011). Wakefield’s article linking MMR vaccine and autism was fraudulent. BMJ, 342, c7452.

Herd immunity. (2011, December). Medical dictionary of health terms. Boston, MA: Harvard Medical School. Retrieved from http://www.health.harvard.edu/medical-dictionary-of-health-terms/d-through-i#H-terms

In emails, Disney worried about measles depiction. (2015, February 14). New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/15/us/in-emails-disney-worried-about-measles-depiction.html?_r=0

International Association for the Measurement and Evaluation of Communication. (2015). Barcelona Principles 2.0. Retrieved from http://amecorg.com/barcelona-principles-2-0

Khazan, O. (2014, September 16). Wealthy L.A. schools’ vaccination rates are as low as South Sudan’s. The Atlantic. Retrieved from http://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2014/09/wealthy-la-schools-vaccination-rates-are-as-low-as-south-sudans/380252

Medina, J. (2015, June 25). California set to mandate childhood vaccines amid intense fight. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/26/us/california-vaccines-religious-and-personal-exemptions.html

Mello, M., Studdert, D., & Parmet, W. (2015). Shifting vaccination politics – The end of personal-belief exemptions in California. New England Journal of Medicine, 373, 785-787.

Parker, L. (2015, February 6). The anti-vaccine generation: How movement against shots got its start. National Geographic. Retrieved from http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2015/02/150206-measles-vaccine-disney-outbreak-polio-health-science-infocus

Pimentel, J. (2015, February 23). Disney raises ticket prices for U.S. theme parks – how far off will $100 a day be for Disneyland? Orange County Register. Retrieved from http://www.ocregister.com/articles/disney-651965-disneyland-day.html

Sawyer, M. (2015). Communicating about vaccines – A never ending conversation. Presentation given at the California Department of Public Health spring 2015 semi-annual meeting. Retrieved from https://www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/cclho/Documents/SAWYER-Communicating%20about%20vaccines%204-14-15.pdf

Seither, R., Masalovich, S., Knighton, C. L., Mellerson, J. Singleton, J. A., & Greby, S. M. (2014, October 17). Vaccination coverage among children in kindergarten – United States, 2013-14 school year. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 63(41), 913-920. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6341a1.htm

Themed Entertainment Association. (2015). TEA/AECOM 2014 theme index and museum index: The global attractions attendance report. Burbank, CA: TEA/AECOM. Retrieved from http://www.teaconnect.org/images/files/TEA_103_49736_150603.pdf

The Walt Disney Company. (2015). A message about the Disneyland Resort from Dr. Pamela Hymel, chief medical officer for Walt Disney Parks and Resorts. Retrieved from http://publicaffairs.disneyland.com/measles-a-message-about-the-disneyland-resort-from-dr-pamela-hymel-chief-medical-officer-for-walt-disney-parks-and-resorts

The Walt Disney Company. (2016a). About the Walt Disney Company. Retrieved from https://thewaltdisneycompany.com/about

The Walt Disney Company. (2016b). Disney history. Retrieved from https://d23.com/disney-history

World Health Organization. (2016, July 11). Measles. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/immunization/diseases/measles/en

Yahr, E. (2014, June 26). Jenny McCarthy, Sherri Shepherd out at “The View” as shake-up continues. Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/arts-and-entertainment/wp/2014/06/26/jenny-mccarthy-sherri-shepherd-out-at-the-view-as-shake-up-continues

Zipprich, J., Winter, K., Hacker, J., Xia, D., Watt, J., & Harriman, K. (2015, February 20). Measles outbreak – California, December 2014-February 2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 64(6), 153-154. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6406a5.htm?s_cid=mm6406a5_w

SHELLEY AYLESWORTH-SPINK, Ph.D., is a senior lecturer in public relations in the London School of Film, Media, and Design at the University of West London. Her research examines the production of public communications from a public relations and mass media perspective focusing on biological matter such as disease outbreaks. Email: shelley.aylesworth-spink[at]uwl.ac.uk.

Editorial history

Received February 24, 2016

Revised July 14, 2016

Accepted July 15, 2016

Published August 29, 2016

Handled by editor; no conflicts of interest