To cite this article

Dimar, K., Kuchar, R. A., & Ragas, M. W. (2016). Book battles: A strategic communication analysis of Amazon.com’s dispute with Hachette Book Group and Authors United. Case Studies in Strategic Communication, 5, article 9. Available online: http://cssc.uscannenberg.org/cases/v5/v5art9

Access the PDF version of this article

Book Battles: A Strategic Communication Analysis of Amazon.com’s Dispute with Hachette Book Group and Authors United

Kelsey Dimar

Liquor Stores N.A.

Rachel Ann Kuchar

Weber Shandwick

Matthew W. Ragas

DePaul University

Abstract

The evolving consumer mindset as it relates to corporate social responsibility—looking into what businesses stand for rather than simply the products or services they sell—was put to the test in 2014 as e-commerce giant Amazon.com chose to engage in an aggressive contract negotiation with supplier Hachette Book Group. Within months, repercussions from the dispute had infuriated a group of 900 influential book authors who formed the grassroots activist organization “Authors United.” The dispute turned public with a war of words that played out through traditional and digital media, threatening to damage Amazon’s shining reputation and calling into question how the retail giant manages and prioritizes its web of stakeholder relationships. This case study reviews and analyzes the nearly year-long conflict from a stakeholder theory and stakeholder prioritization perspective. This case offers important implications for strategic communication students and professionals, suggesting consumers may not be as moved by socially irresponsible corporate behavior as often believed.

Keywords: Amazon.com; Jeff Bezos; Hachette; Authors United; stakeholder relationships; corporate reputation; corporate social responsibility; grassroots activism; activists

“When you are eighty years old, and in a quiet moment of reflection narrating for only yourself the most personal version of your life story, the telling that will be most compact and meaningful will be the series of choices you have made. In the end, we are our choices.” – Jeff Bezos, Founder, Amazon.com (Solomon, 2012, para. 1)

Introduction

In the early 1990s, a slight, Princeton-educated Wall Street trader dreamed of creating an “everything store”: a place that could connect consumers with suppliers on the emerging frontier referred to then as the World Wide Web (Stone, 2013). From its very inception, the fledgling concept focused on how to please its then-unknown hordes of customers. That dreamer, named Jeff Bezos, soon broke ground on his superstore plan by opening a completely internet-based bookstore, which was already in existence on several other internet websites (Stone, 2011). Two decades later, Bezos’ creation, Amazon.com, would become as ubiquitous as the corner market.

Amazon rose to power on the back of its bookselling business, which constitutes at least 41% of all new book sales in the United States (Milliot, 2014). For 2015, Amazon’s net sales—now including many items other than books—were $107 billion, making it one of the world’s largest retailers (“Amazon.com Announces,” 2016). When focusing on media sales (including books), Amazon’s revenue for this category was still quite substantial at $22.5 billion for 2015 (“Amazon.com Announces,” 2016). Amazon’s total revenue now places it at number 29 on the FORTUNE 500 list of the largest companies in America (“Amazon.com,” 2015). Impressive revenue growth over the past two decades has generally wowed Wall Street with the company sporting a market value of $260 billion as of March 2016 (YCharts.com, 2016), boosting the e-commerce giant well into the ranks of the world’s 100 most valuable companies based on market capitalization (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2015).

These numbers are impressive. As a result of its growing power and fixation on customer satisfaction (“Leadership Principles,” n.d.; “Overview,” n.d.), Amazon has been well positioned to demand lower prices from its suppliers, and has been able to employ aggressive business tactics—perceived by some as ruthless—in negotiating with this stakeholder group (Krugman, 2014; Stone, 2011, 2013). This aggressive approach to stakeholder management and prioritization (Plowman & Rawlins, 2010; Rawlins, 2006) thrust Amazon into the public eye in 2014 when an American subsidiary of a French publishing organization, Hachette Book Group, a major New York publisher, did not accept Amazon’s requests to cut prices on Hachette’s e-book offerings (Bertrand, 2014). In response, and without warning or fanfare, Amazon appeared to increase prices on Hachette books for sale on Amazon.com, purposely delay the shipping times on Hachette book orders, and direct shoppers to non-Hachette published titles. Such behavior could be viewed as not just aggressive, but unethical and unjust (Frizell, 2014).

Corporate Social Responsibility and Amazon

Amazon’s management philosophy has long been that the customer comes first and that, if the customer is satisfied, other stakeholders should benefit (“Leadership Principles,” n.d.; “Overview,” n.d.). However, the consumer mindset about the role of business in society and business practices is evolving, making it more difficult than ever for large corporations to manage the web of stakeholder relationships and strongly prioritize one stakeholder group over another (Coombs & Holladay, 2012; Ragas & Culp, 2014). Consumers say they want to support businesses that behave in a socially responsible fashion and provide shared value for all stakeholders, including suppliers. Yet, consumers may still place getting a good deal, quality, and convenience above all else when choosing which organizations will gain their trust and support (Christ & Sandor, 2015). For example, while research indicates (e.g., Cone Communications & Echo Research, 2013) that less than one out of 10 members of the public believe that a firm’s only purpose is to make money, does a company’s corporate social responsibility (CSR) policies and decision-making truly drive consumer behavior?

This supposed evolving consumer mindset—looking into what businesses stand for and how they operate, rather than simply the products or services they sell—was put to the test in 2014 as Amazon chose to engage in a dispute with Hachette. Soon thereafter, hundreds of authors organized and activated against “the everything store.” A practical test of stakeholder management theory (Freeman, 2010; Freeman, Harrison, & Wicks, 2007) and stakeholder prioritization (Plowman & Rawlins, 2010; Rawlins, 2006), the following case reviews and analyzes the lead up to the dispute, the perspective of the major stakeholder groups affected, the business and communication strategy and tactics used by Amazon and stakeholders during the dispute, and the evaluation and outcomes of this dispute. This case concludes by providing implications relevant for both students and professionals tasked with helping manage the web of stakeholder relationships and CSR in an increasingly complex business environment.

Corporate Social Responsibility and Consumers

The role and mindset of the consumer has drastically changed over the last two decades due in part to the widespread adoption of digital and social media. Consumers seem to expect more from the brands they support; they actively keep tabs on firms’ CSR efforts and how they treat all stakeholders—not just customers. According to a Nielsen study, “fifty-five percent of global online consumers across 60 countries say they are willing to pay more for products and services provided by companies that are committed to positive social and environmental impact” (“Global Consumers,” 2014, p. 6). This is just one piece of evidence out of many examples that consumers expect firms to live up to their CSR efforts, and treat all stakeholders within their network with dignity and respect (Ragas & Culp, 2014). But do consumers actually reward (or punish) CSR behaviors with their wallets?

Background

The Everything Store

Jeff Bezos brought Amazon.com to life in 1994. Headquartered in Seattle, Washington, Amazon started as an online bookstore and quickly diversified into a one-stop retail destination by offering DVDs, electronics, furniture, toys, and apparel for sale. Amazon went public in 1997, with Bezos penning the fundamental foundation for Amazon’s success in the first shareholder letter: “Start with customers, and work backwards. … Listen to customers, but don’t just listen to customers—also invent on their behalf. … Obsess over customers” (Stone, 2013, p. 11).

A strong element of Amazon’s business model is focused around innovation on behalf of customers, whether that is expanding product categories or discovering ways to lower the cost of products and streamlining the delivery process. Amazon’s mission is “to be Earth’s most customer-centric company where people can find and discover anything they want to buy online” (“Overview,” n.d., para. 1). Amazon’s 14 stated Leadership Principles also drive home its focus on customers. Not surprisingly, the first leadership principle is titled “Customer Obsession” (“Leadership Principles,” n.d.). Over the years, Amazon has grown to be known as one of the most efficient, seamless e-commerce platforms in the world, operating in more than 180 countries (“Overview,” n.d.). With 97,000 full-time and part-time employees worldwide, Amazon has strategically placed warehouses and distribution centers across the globe to deliver its products to even the most reclusive locations (Wulfraat, n.d.). See Figure 1 for an image of a massive Amazon fulfillment center in Phoenix, Arizona.

Figure 1. An Amazon fulfillment center in Phoenix, Arizona (Source: Paul Morris / Bloomberg, from Dallas Morning News’ Biz Beat Blog).Amazon believes that the right way to build a brand and run a business is by delivering a great service that customers will want. According to Bezos, “you earn reputation by trying to do hard things well. People notice that over time. I don’t think there are any shortcuts” (Hof, 2004, para. 4). By remaining customer-driven, Amazon’s goal to continually build up the brand through innovations has transformed the customer experience. Offering a dependable, efficient, and effortless service has earned Amazon an enviable position on many corporate reputation and brand value rankings in recent years.

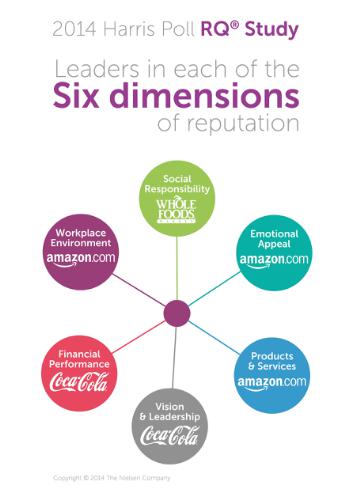

The Harris Poll Reputation Quotient (RQ) surveys more than 18,000 members of the U.S. general public to measure the reputations of the 60 most visible companies in the country. Conducted since the late 1990s, the Harris RQ poll is one of the most widely followed measures of corporate reputation by strategic communication professionals, business managers, news media and other stakeholder groups (Ragas & Culp, 2014). The 2014 RQ survey was conducted in late December 2013 through early January 2014, several months before the public first became aware of the dispute between Amazon, Hachette, and the book authors.

In 2014, for the sixth year in a row, Amazon was rated by the RQ survey methodology as having an “excellent” reputation score (83.87). In fact, this score placed Amazon at the top of the RQ rankings for 2014 with only a total of nine companies having an RQ score of more than 80 (see Figure 2). Amazon has managed to build an intimate relationship with its customers, with more than nine in 10 members of the public recommending Amazon to a friend (“Amazon.com Retains,” 2014). Personal recommendations are a strong determinant of reputation, and Amazon has been able to get the public talking about its customer-driven business model. Of course, word-of-mouth can swing the other way as well and Amazon’s reputation was on the line during its 2015 dispute.

Figure 2. 2014 Harris Poll RQ study: Leaders in each dimension of reputation (Source: 2014 Harris Poll RQ).Amazon’s Financial History: Roots in Books

Amazon entered the marketplace in the mid-1990s as an online bookstore, an idea that spurred as a result of the growing demand for books at a lower cost. This was during the time of the internet boom, where many businesses were taking their merchandising efforts online. Reading into the industry trends at the time, Amazon’s goal was to revolutionize the retail space and capitalize on an idea that could either have great success or flop completely. Within Amazon’s first two months of launching its online book hub, sales reached $20,000 a week, with books being sold in all 50 states and 45 countries (Spiro, 2014). In 2007, Bezos introduced the Amazon Kindle e-Reader hardware device to the marketplace, something that was unexpected from a company known as an online retailer (Spiro, 2009; Stone, 2011). The Kindle was easy to use and allowed users to download a book quickly from Amazon’s extensive online library. With this product, Amazon transformed the book industry. The Kindle, in its various iterations, is still the number one product that consumers associate with Amazon (Stone, 2011, 2013).

Amazon’s annual revenue from book sales is reportedly at least $5.25 billion (Bercovici, 2014). Specifically within the growing e-book category, Amazon has an approximate 65% market share, leading the pack against rivals Apple and Barnes & Noble (Bercovici, 2014). Having such a strong hold on the publishing industry, Amazon is influential when it comes to e-book price setting and contractual terms with even the world’s largest publishing houses.

Amazon’s financial performance, at least in terms of revenues, has been on an unstoppable trajectory since its inception. Analysts estimate that Amazon has increased its sales, on average, by more than 30% on an annual basis (Stone, 2013). As shown in Figure 3, despite soaring revenues, Amazon’s profit margins have been meager or even nonexistent, with the company losing tens of millions of dollars a year at times in its history.

Figure 3. Amazon.com’s revenue and profit, 2004-2014 (Source: International Business Times).Amazon’s steady revenue gains, but limited profitability, can be explained in part by its devotion to satisfying customers and growing its customer base, which is demonstrated by steep discounts and free shipping (Clark & Young, 2013).

Despite its negligible profit margin, Amazon has long been a Wall Street favorite as investors have fixated on its growth rate and long-term profit potential instead of its near-term limited profits or annual losses. Amazon investors have argued that Amazon could be quite profitable if it reduced its investment in new infrastructure, such as warehouses, and scaled back on the introduction of new services. As of March 2016, Amazon’s market capitalization was around $260 billion, making it one of the world’s most valuable firms (YCharts.com, 2016).

Hachette Book Group: Supplier Background

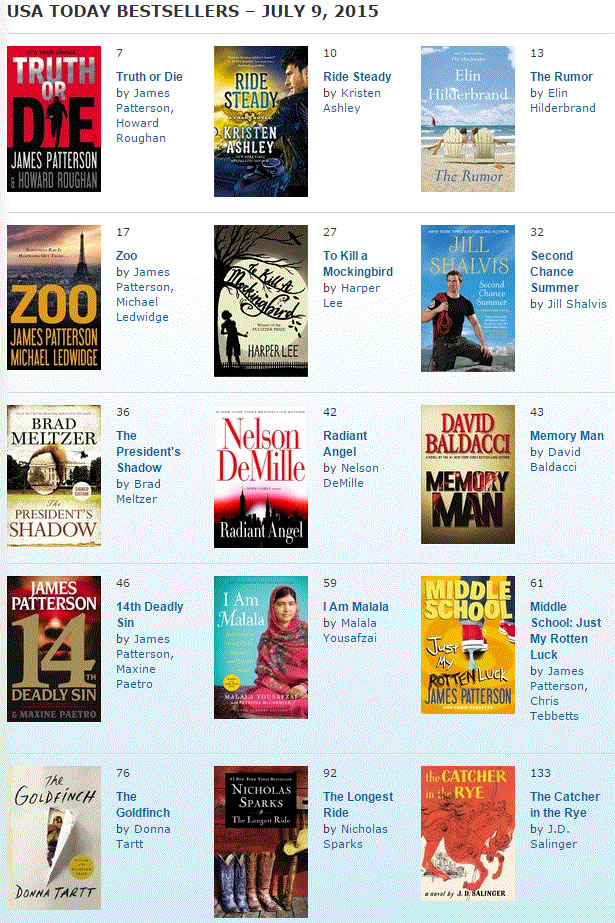

Amazon can thank New York City-headquartered Hachette Book Group, one of its many suppliers, for contributing to its continued growth and success. Hachette represents many best-selling authors, such as J.K. Rowling, Mitch Albom, Donna Tartt, and Stephanie Meyer (“About Us,” 2016; see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Best-selling titles by Hachette Book Group authors (Source: Hachette Book Group).Hachette produces about 1,000 books a year, and is an influential and well-regarded player in the publishing world (Frizell, 2014). Hachette’s parent company, France-based Hachette Livre, published 20,359 titles in 2014 and reported total sales of €2 billion in 2014 (“Global Publishing,” 2015). Hachette Livre is itself a subsidiary of Lagardère, a global media company that is publicly traded in Europe (“Global Publishing,” 2015).

On its website, Hachette highlights its mission statement and corporate social responsibility efforts (“About Us,” 2016). Explicit in its corporate persona is its desire to “publish great books well” (“About Us,” 2016, para. 4); implicit is its belief that authors should be paid fairly for their work—a requirement under the “Lang Law” in Hachette’s French homeland, which seeks to stabilize book prices and revenue so that publishing is sustainable for many (Anderson, 2011). Hachette’s culture is reinforced by its CEO, Michael Pietsch, who has led Hachette since 2012. Pietsch is known for being “hands-on”; he works in an open space alongside employees in Hachette’s Midtown Manhattan office (Mahler, 2014).

Hachette, like other New York publishing houses, welcomed partnering with Amazon in the 1990s in an effort to diversify its sales from other conglomerates such as Borders and Barnes & Noble (Stone, 2013). Through the partnership, Hachette and Amazon set the pricing of Hachette-published books and Amazon’s share of those sales, terms the parties must re-negotiate from time to time (Bertrand, 2014). Amazon, being the super-retailer that it is, has immense leverage in its negotiations with Hachette and has been transparent about its goal to drive down prices in order to please its customers (Lashinsky, 2014). Adding to Amazon’s influence over Hachette is the fact that 60% of Hachette e-books are sold on Amazon.com (compared with Barnes & Noble, which sells 18% of Hachette e-books) (Kozlowski, 2014).

Brief Timeline of Amazon-Hachette Negotiations

The following timeline outlines the major events that transpired during and after the negotiations between Amazon and Hachette over the renewal of Hachette’s supplier agreement. These negotiations started in early January 2014, when Amazon sent an updated renewal offer to Hachette, and the two parties did not come to a new agreement until almost a year later in mid-November 2014. In the interim, what started as private negotiations spilled out into the open, first as the media began to write about how Amazon was making it difficult and more expensive to order Hachette titles on Amazon.com, and later in summer 2014 as a group of activist book authors, calling themselves “Authors United,” chided Amazon for its treatment of Hachette.

| Timeline of Events Surrounding Amazon and Hachette’s Negotiations |

|---|

|

Strategy

In an ideal world, Amazon and publishers like Hachette would live together in harmony. However, Amazon’s increasing market share has led to tension with New York publishing houses, which tend to band together when it comes to Amazon—even though the publishers compete with one another for top authors, employees, customers and, ultimately, sales. Together, they are known as the “Big Five”: Penguin Random House, Macmillan, HarperCollins, Simon & Schuster, and Hachette—which is the smallest of the five houses (Lashinsky, 2014; Quinn, 2014). This unification is due to a growing fear of Amazon’s ever-increasing retail market share (Greenfield, 2014b). As Stone (2013) describes in The Everything Store, when it comes to its suppliers, Amazon “wield[s] its market power neither lightly nor gracefully, employing every bit of leverage to improve its own margins and pass along savings to customers” (p. 278).

Therefore, in early 2014 the publishers stood their ground to protect whatever advantage they had over Amazon. Even before its launch, Amazon knew that its labor of love, the Kindle, would thrive only with strong e-book sales (Stone, 2013). Of course, publishers like Hachette wanted their books sold on Kindle, but Amazon’s increasing market share in e-books was disconcerting based on Amazon’s notorious negotiating tactics (Stone, 2011). This fear was justified given Amazon’s tangle with Macmillan in 2010 over e-book prices, which led to Amazon removing Macmillan titles from its site altogether (Stone & Rich, 2010).

A Book Battle Brews

The sticking point between Amazon and Macmillan was the publisher’s request to set a $15 floor for e-book sales, which Amazon rejected (Stone & Rich, 2010). Soon thereafter, the parties settled, but the Amazon vs. publishing world dispute would continue due to U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) accusations that the Big Five and Apple were colluding to fix the prices of e-books (Musil, 2012). The publishing houses settled, but Apple fought on and was sued (Apple settled with the DOJ in July 2014). In early January 2014, Hachette was the first major publishing house to negotiate a contract renewal with Amazon after the settlement. This time Amazon would find itself facing a more determined supplier and stakeholder.

Stakeholder Perspectives

By striving to always improve the consumer experience, Amazon’s customer-centric business model has been one of the main drivers of its success. As Amazon has evolved over the years, adding new products and services to its extensive portfolio, so has the consumer mindset. Consumers expect businesses to behave in a socially responsible manner that not only benefits them, but all stakeholders who have a hand in the company. However, when it comes down to the benefits that a company offers, whether that be low prices or seamless delivery, consumers still want a good deal (Christ & Sandor, 2015). Amazon believes that if the customer is happy all other stakeholder groups should benefit, and this is how Amazon approached the Hachette dispute. Amazon prioritized its customers over all other stakeholder groups, and this decision benefited Amazon’s business performance, showing that (contrary to some expectations) CSR may not always be a driving factor for consumers in winning and keeping their business.

It is instructive to examine the various stakeholder group perspectives that evolved throughout this dispute. To fully understand the nature of this case, what follows is an overview of each major stakeholder group involved in this dispute and its relationship with Amazon.

Consumers. Under Bezos, Amazon has taken a unique path in efforts to decode its target. Coddling his nearly 164 million customers, Bezos routinely leaves one seat open at the conference table for the customer, stating that it is “the most important person in the room” (Anders, 2012, p. 1). Figuring out what the customer wants, whether that is new products or services, before they check out, is the primary driver behind Amazon’s success. From mid-2003 to early 2007, Amazon’s performance was flat due to an influx of similar companies all fighting for the same market share (Anders, 2012). Behind the scenes Bezos was secretly building the brand, focusing on one theory alone: If Amazon lets customers set the specs, it could conquer any number of consumer products and services (Anders, 2012). With that being said, it is important to note that what a company does outside the workplace appears to matter more now than ever. One would assume that Amazon’s corporate reputation would suffer due to the negative media surrounding the Hachette dispute, but, based off recent Harris RQ data, Amazon’s reputation is as strong as ever. Perhaps Amazon’s customer-centric business model is so appealing that consumers overlook its questionable CSR efforts? With its low prices and product/service variety, perhaps consumers focus more on the direct product/service benefits they are receiving, and less on what Amazon is doing from a CSR perspective, including its treatment of suppliers.

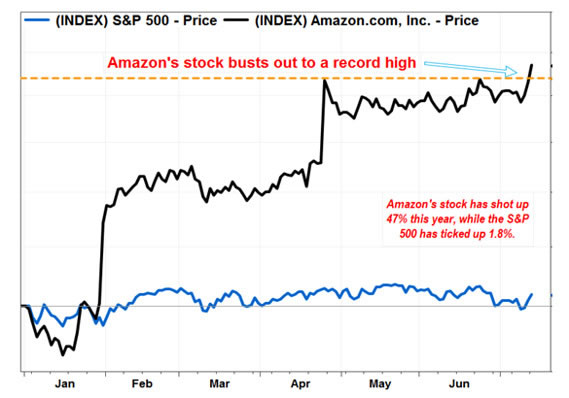

Investors. Based off Amazon’s investor model, focusing on long-term customer loyalty and new product opportunities is believed to create bigger long-term profits (Blodget, 2013). Many investors admire this operating model that encourages companies to “invest more of today’s profits in tomorrow’s opportunities, product development, customer loyalty, and dedicated employees” (Blodget, 2013, p. 1). Investors in Amazon shares have focused on the company’s growth strategy and diversification across all product categories. When Hachette confronted Amazon over the renewal of Hachette’s supplier agreement, investors largely disregarded the dispute and focused on Amazon’s business growth and financial performance as a whole. In the aftermath of the dispute with Hachette and the authors, Amazon enjoyed a banner year in the stock market in 2015, with record revenue driving a whopping 118% increase in Amazon’s stock price (Dulaney, 2015).

Book Publishers. As one of the many suppliers for Amazon, book publishers have had a trying relationship with the retail giant. Entering the digital age in 1994, Amazon provided a new revenue stream for book publishers as e-books grew in popularity. As brick-and-mortar stores continue to shut their doors, book publishers are more reliant on e-commerce sales. Claiming more than two-thirds of the U.S. online book market, Amazon has set the standards for this industry in transition. Many publishers, including the Big Five, are worried that Amazon’s grip on the industry could doom authors and publishers collectively as their autonomy and ability to regulate the industry is being compromised. However, in order to make money and continue publishing authors in general, book publishers need consumers to continue purchasing books from Amazon.

The Author Collective. Another key stakeholder group that became entangled in Amazon’s extensive stakeholder web was the author collective, Authors United. Members of this activist group have a stated mission to “put an end to the sanctioning of books” and this group calls books “the very foundation of our culture and democracy” (“Letter to Amazon.com,” 2014, para. 11). Throughout the development of the Hachette case, authors who were not even a part of the Big Five or a supplier of Amazon spoke out against Amazon’s actions, advocating for authors’ rights as a whole. As a result, the full-page Authors United advertisement in August 2014 brought the Amazon and Hachette dispute out of the publishing world and made it more of a mainstream, public topic (Brown, 2014).

Execution

At the start of 2014, Amazon and Hachette set out to negotiate the terms of their new contract. Amazon reportedly demanded that Hachette lower its e-book prices to $9.99, which Hachette rebuffed (Trachtenberg, 2014). In response, in February and March 2014, Amazon began to quietly manipulate Hachette-sourced products on Amazon.com, making it more difficult for consumers to order books by Hachette authors (“Hachette Rebuffs,” 2014).

Amazon’s Response During Hachette Negotiations

According to published reports, Amazon slowed down Hachette shipping times (2-5 week delays), raised Hachette book prices, and redirected buyers to books by other publishers. (“Hachette Rebuffs,” 2014; Trachtenberg, 2014). Amazon also reportedly refused to list Hachette books for pre-order and listed Hachette books at full-price while continuing to discount books from other publishing houses (Frizell, 2014). While these tactics are referred to as “sanctioning” books, they are not illegal (Frizell, 2014). Hachette stayed silent during the early months of this conflict and dug in its heels. Hachette was said to be taking a “French” approach, focusing on long-term results instead of the more American way of quarterly thinking (Feldman, 2014).

Authors United: Grassroots Activism

By summer 2014, Hachette Book Group authors were feeling the pain of Amazon’s actions, and were understandably upset about being caught in the middle of the conflict. In early August 2014, best-selling writer Douglas Preston penned an open letter to Amazon executives (on AuthorsUnited.net, a site he set up) asking Amazon to stop using authors and books as bargaining chips in its dispute (Streitfeld, 2014). In an interview with Mark Brown (2014) of The Guardian, Preston explained his perspective and motivation for writing the letter:

Amazon has been throwing its weight around for quite some time in a bullying fashion and I think authors are fed up. We feel betrayed because we helped Amazon become one of the largest corporations in the world. We supported it from the beginning, we contributed free blogs, reviews, and all kinds of stuff that Amazon asked us to do for nothing. We thought we had a fairly good partnership but in the last half dozen years Amazon’s corporate behaviour has not supported authors at all. (para. 7)

Before long, more than 900 authors had signed on to Preston’s missive, which was published in a very high profile fashion—a full-page ad in the Sunday edition of The New York Times—on August 10, 2014 (Brown, 2014; “Over 900 Authors,” 2014). In the open letter, the grassroots group of activist authors, who referred to themselves as “Authors United,” asked Amazon to “put an end to the sanctioning of books” (“Letter to Amazon.com,” 2014, para. 11).

The names at the bottom of the Authors United letter were impressive in number, and included literary giants such as Stephen King, John Grisham, and Anna Quindlen, as well as many authors not even published by Hachette (Brown, 2014; “Over 900 Authors,” 2014). The confederation of authors made it clear that they did not see books as “consumer goods,” and implied that Amazon was treating their literary work and the books of others as such (“Letter to Amazon.com,” 2014, para. 8). The letter also included Bezos’ email address and encouraged readers to contact him directly (Brown, 2014; “Over 900 Authors,” 2014).

The full-page Authors United ad brought the Amazon and Hachette dispute out of the publishing world and into the hands of readers (Brown, 2014; “Over 900 Authors,” 2014; Streitfeld, 2014). The campaign elevated the dispute to a debate over whether Amazon had grown too powerful and was taking advantage of some of its stakeholders (Krugman, 2014). Amazon’s choice to engage in a contract negotiation with Hachette in an aggressive and perhaps even unethical fashion may have set the company up for a hit to its stellar reputation.

Amazon’s Choices: Policies and Strategic Communication

Amazon has generally approached strategic communication management from a command-and-control perspective (Miller, 2014). As described by Salon.com, “Amazon has long been a tight-lipped operation, refusing to release hard information to the press and communicating through the rather arcane medium of the forums of its own site” (Miller, 2014, para. 6). Amazon took a similar approach to its interactions with the news media and authors during the Hachette negotiations, driving home the point in a series of controlled messages that these negotiations were in the best interest of its customers.

In late May 2014, Amazon released its first detailed official statement about its negotiations with Hachette, choosing to release the statement via the public Kindle forum on Amazon.com. In a statement issued by “The Amazon Books Team,” the company acknowledged that the two sides had been “unable to reach a mutually-acceptable agreement on terms” and were “not optimistic that this will be resolved soon” (The Amazon Books Team, 2014a, para. 2). Amazon went on to say in its statement that “when we negotiate with suppliers, we are doing so on behalf of our customers” (The Amazon Books Team, 2014a, para. 3). Amazon concluded by adding: “we also take seriously the impact it has when, however infrequently, such a business interruption affects authors” (The Amazon Books Team, 2014a, para. 5). At the end of July 2014, Amazon provided another update and official statement, once again issued via the Kindle forum on Amazon.com (The Amazon Books Team, 2014b). In this statement, the Amazon Books Team (2014b) outlined why it believed lower e-book prices are important, including the customer paying less for books and lower prices resulting in potentially greater demand and more copies sold (“the total pie is bigger” in the words of Amazon) (para. 6).

Amazon’s most notable response outside of the forums came the same weekend in August that the Authors United ad that ran in The New York Times. Amazon mimicked the activist authors’ group by posting its own response, “A Message from the Amazon Books Team” (n.d.) to a new website it set up called ReadersUnited.com. In an open letter, Amazon explained that it had “made three separate offers to Hachette to take authors out of the middle” but that Hachette “quickly and repeatedly dismissed these offers” (“A Message,” n.d., para. 11). According to Amazon, it would “never give up [its] fight for reasonable e-book prices. We know making books affordable is good for book culture.” (“A Message” n.d., para. 12).

Amazon’s CSR Strategy After the Hachette Scandal

On October 20, 2014, Amazon and Simon & Schuster, another member of the Big Five, announced that a new compromise deal had been reached between the two sides. Amazon and Simon & Schuster’s negotiations had been far less public than Hachette, but the agreement with this publisher may have set the stage for Amazon and Hachette to find common ground. For a rare moment, Amazon’s devotion to its customers was eclipsed by its activist author stakeholder group, in addition to its publisher suppliers and, of course, its profit-driven investors. Amazon decided it was time to end the conflict. On November 13, 2014, after nearly a year of back-and-forth, Amazon and Hachette reached a confidential settlement, which is said to have kept e-book prices at a stable level in protection of publishers (McGee, 2014).

Evaluation

Did Amazon’s tangle with book publishers and suppliers contribute to a weakened view of the company? The assumption might be “yes,” but the numbers indicate otherwise. Given the negative media attention that Amazon received, some decline in Amazon’s reputation might have been expected (Carroll, 2011). In this regard, reputation studies show that Amazon was very successful in defending its standing with its U.S. consumer stakeholder group (Reputation Institute, 2014).

Consumers Maintain Support

Corporate reputation scholars would generally predict that Amazon’s reputation should decline due to the negative media attention it received, but this is not what the Harris RQ data indicates (Carroll, 2011). In the 2015 RQ rankings, Amazon’s reputation score remained sterling and virtually unchanged from the year before the Hachette dispute (83.72 in 2015 compared with 83.87 in 2014) (“Regional Grocer,” 2015). Amazon’s reputation score topped all of the 100 most visible U.S. companies in the 2015 RQ rankings, except for Wegmans Foods Markets (RQ score of 84.36) (“Regional Grocer,” 2015).

This lack of a dent in Amazon’s reputation could be a sign of the decline in the influence of traditional elite media on the public (does The New York Times pack the agenda-setting punch it once did?) or it could be a sign that the Hachette and Authors United argument did not resonate with the public (how sympathetic is the average American to the plight of the New York literary establishment?). This case may be an example of the public having intentions to support good corporate citizens on paper, but, all else being equal, are more drawn to convenience and habit.

In short, this case suggests that, while consumers may say that a firm’s treatment of all stakeholders and good CSR are important to them, many customers still privilege factors like price, convenience, and reliability when making purchase decisions. For example, Adam Lashinsky, a journalist and author who believes his own Hachette-published book was manipulated on Amazon’s website during the conflict, finds Amazon “icky.” (Lashinsky, 2014). Nonetheless, Lashinsky says he still buys from Amazon due to convenience and prices.

Investor Support Holds

On the other end of Amazon’s stakeholder spectrum, investors also seem to have cast a blind eye to the publisher and author disputes, as Amazon touted its continued growth and further expansion into other businesses. Amazon’s stock price surged in the first half of 2015 (see Figure 5), and by the end of the year, it was being called an “unstoppable” stock with the company’s share price more than doubling in 2015 (Dulaney, 2015; Reeves, 2015).

Figure 5. Amazon.com’s stock price performance, first half of 2015 (Source: MarketWatch).In short, there are no signs that Amazon’s tactics with book publishers and authors bothered major Amazon shareholders, as Amazon’s financial performance actually improved.

Book Publishers and Authors Continue Engagement

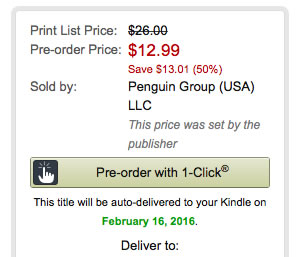

Book publishers and authors continue to peddle their wares to Amazon following the book disputes that touched the Big Five. In settling the disputes with its largest book suppliers, Amazon demonstrated that it wants (and needs) to work together with publishers and authors to bring its customers what they need at reasonable prices. Publishers, however, may be careful what they wish for. In the wake of its book battles, Amazon appears to have made changes to bring transparency into the fold and highlight suppliers’ influence on its prices (Posadas, 2016).

Now, Amazon.com indicates which publisher consumers are purchasing from (e.g. Penguin Group), and also notes when a price has been “set by the publisher.” In so doing, customers can see why an e-book is priced the way it is—per direction from the publisher (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Amazon.com indicates pricing is set by the publisher (Source: Amazon.com).

Analysis and Discussion

While Amazon seems to have escaped the conflict with Hachette and Authors United with its reputation unscathed, being the subject of headlines like “Amazon must be stopped” and “Inside Amazon: Wrestling big ideas in a bruising workplace” (Foer, 2014; Kantor & Streitfield, 2015) are hardly shining moments. There are signs that Amazon may be rethinking its approach to stakeholder relationship management and fairly opaque strategic communication efforts. In February 2015, the company announced the hiring of Jay Carney, the former White House press secretary and Time magazine journalist, as its senior vice president of global affairs, a new position responsible for Amazon’s public relations and public policy (Streitfeld, 2015a).

Amazon Hints that CSR Matters

According to at least one report, Bezos “has been unhappy with some of the negative storylines around Amazon.” (Del Rey, 2015, para. 4). Carney reports directly to Bezos, highlighting the importance of this newly-created chief communication officer position. While Carney’s Beltway connections undoubtedly help Amazon with lobbying, his hiring could indicate that Amazon intends to work more proactively and productively with its stakeholders, increasing disclosures and promoting greater dialogue (Del Rey, 2015; Streitfeld, 2015a).

Amazon undoubtedly still values its customers, but there are indications that it is trying to listen more closely to other stakeholders as well, better balancing the interests of these different groups. For example, in June 2015, Amazon announced that it was changing the payment system for self-published authors who participate in its Kindle Owner’s Lending Library and Kindle Unlimited services due, it says, to author feedback (Hern, 2015). These authors are now paid based on the length of each book and the number of pages read (Hern, 2015).

The Hachette and Authors United experience, in which Amazon was framed as a monopolist with thuggish tendencies, may have shown Bezos and his colleagues the benefits of a kinder, gentler, and more transparent approach to stakeholder management. Amazon faces a variety of challenges that will likely put Amazon leadership to the test when it comes to CSR and corporate citizenship in the years to come. This includes harsh criticism of Amazon’s workplace culture and treatment of its employees (Kantor & Streitfield, 2015), and the Rev. Jesse Jackson pushing for greater diversity and inclusion within Amazon’s workforce (Demmitt, 2015; Greene, 2015).

Implications for Strategic Communicators

For the time being, Amazon’s customers, suppliers, and investors are “standing by their man.” One would think the actions taken by Amazon against book publishers and authors would cause the company’s stakeholders to question their allegiance, but over time it seems that the scuffle with Hachette has had little to no impact on the company’s reputation. What does this fact tell practitioners about CSR if Amazon can face such unflattering media attention and still succeed? Does good CSR really matter, and does it depend on the stakeholder and/or issue?

According to much of the research on the subject, the answer would be “yes.” In this case, however, Amazon played hardball at best with some stakeholders and acted unethically at worst—yet it remains stronger than ever. Consumers still shop the site at a rate of 188 million visits per month, pushing its revenue higher and higher (Flynn, 2016; Statista.com, 2016).

Why does the Amazon/Hachette case present a different ending than what would be expected by CSR advocates? The answer might be because, like it or not, CSR efforts are simply not always given a heavy weighting in consumer decision making. For example, a recent study showed that only a quarter of consumers were willing to pay $0.50 more for a pair of socks that were made in “good working conditions,” and only half of consumers bought the socially-responsible socks when they were the same price as the alternative. (Bader, 2014).

What this case demonstrates is that, contrary to the views of CSR advocates, consumers are not always turned off by “bad” corporate behavior, especially if the behavior benefits their wallets. Practitioners should consider that, while consumers’ mindsets have shifted to become more cognizant of good CSR, it might, in reality, not always be as essential as assumed. Further, a customer-first approach to stakeholder management when stakeholder positions are in conflict can work (Plowman & Rawlins, 2010; Rawlins, 2006), even when aspects of such behavior might make business ethicists cringe (Freeman, 2010). Given Amazon’s strong reputation and the years of goodwill it has built up with consumers, it will likely take an even more controversial business decision (e.g., involving the environment, workers, or a social issue) for consumers and other stakeholders to more strongly react to Amazon’s actions, and to penalize it meaningfully with their wallets (Christ & Sandor, 2015). The sheer market dominance and growth of Amazon is likely to place its business practices under a more skeptical spotlight in the years ahead, just as happened to rivals Wal-Mart and others in years past (Hanauer, 2015).

Conclusion

As Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos has said, “in the end, we are our choices” (Solomon, 2012, para. 1). For Amazon, it has traditionally chosen to focus on satisfying its customers, driving down prices for its customers at almost any cost. In the case of its dispute with Hachette and the activist authors, Amazon appeared to engage in non-socially responsible behavior, but its reputation and business performance were not punished by its customers. As such, this case provides an important exception to the rule. Good CSR clearly matters and organizations should try to treat all stakeholders fairly and respectfully, but this case reveals that consumers, at least sometimes, are still willing to very much look the other way if their own direct interactions with the organization in question remain favorable and rewarding.

Discussion Questions

- Do you believe Amazon behaved appropriately in its negotiations with Hachette Book Group and in the public statements it made about these negotiations? Would you have done anything differently from a business strategy and strategic communication perspective if you were Amazon’s CCO or CSR chief? If so, what?

- How could Amazon have more effectively used strategic communication to make its case to consumers and other stakeholders that it was taking the right stance with Hachette and Authors United? What did you think of Amazon’s messages posted to its online forums?

- What did you think of the use of strategic communication by Authors United to make its case to consumers and other stakeholders? How would you judge the performance of this grassroots activist group? Would you recommend changes to its strategy and/or tactics?

- Were you surprised that Amazon’s reputation among the U.S. public did not decline based on Harris RQ data? Why do you think Amazon’s reputation among the public did not decline in the face of the significant negative attention? Do you think Amazon’s reputation among suppliers and other partners was hurt?

- Given the evolving consumer mindset and the expectation for greater corporate social responsibility, do you think Amazon will need to change its business practices and/or strategic communication style and substance regarding such practices in the years ahead? Or will Amazon succeed by continuing to prioritize its customers over other groups? Why or why not?

References

About us. (2016, June). Hachette Book Group. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.hachettebookgroup.com/about

The Amazon Books Team. (2014a, May 27). Hachette/Amazon business interruption. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from https://www.amazon.com/forum/kindle/ref=cm_cd_search_res_ti?_encoding=UTF8&cdForum=Fx1D7SY3BVSESG&cdPage=1&cdSort=oldest&cdThread=Tx1UO5T446WM5YY#MxVV8B80GZQLRM

The Amazon Books Team. (2014b, July 29). Update re: Amazon/Hachette business interruption. Amazon.com Kindle forum. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from https://www.amazon.com/forum/kindle/ref=cm_cd_rvt_np?_encoding=UTF8&cdForum%20=Fx1D7SY3BVSESG&cdPage=1&cdThread=Tx3J0JKSSUIRCMT#CustomerDiscussionsNew

Amazon.com. (2015). FORTUNE.com. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://fortune.com/fortune500/amazon-com-29

Amazon.com announces fourth quarter sales up 22% to $35.7 billion [Press release]. (2016, January 28). Amazon.com Investor Relations. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://phx.corporate-ir.net/phoenix.zhtml?c=97664&p=irol-newsArticle&ID=2133281

Amazon.com retains highest reputation ranking in 15th annual Harris Poll Reputation Quotient study [Press release]. (2014, April 29). PR Newswire. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/amazoncom-retains-highest-reputation-ranking-in-15th-annual-harris-poll-reputation-quotient-study-257149631.html

Anders, G. (2012, April 4). Inside Amazon’s idea machine: How Bezos decodes customers. Forbes.com. Retrieved on August 18, 2016, from http://www.forbes.com/sites/georgeanders/2012/04/04/inside-amazon/#69d629207ae2

Anderson, N. (2011, May 25). France attempts to impose e-book prices on Apple, others. ArsTechnica.com. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2011/05/france-attempts-to-impose-e-book-prices-on-apple-others

Bader, C. (2014, April 21). Why corporations fail to do the right thing. TheAtlantic.com. Retrieved on August 18, 2016, from http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/04/why-making-corporations-socially-responsible-is-so-darn-hard/360984

Bercovici, J. (2014, February 10). Amazon vs. book publishers, by the numbers. Forbes.com. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.forbes.com/sites/jeffbercovici/2014/02/10/amazon-vs-book-publishers-by-the-numbers/#544b6d2465a3

Bertrand, N. (2014, October 7). How Amazon’s ugly fight with a publisher actually started. BusinessInsider.com. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.businessinsider.com/how-did-the-amazon-feud-with-hachette-start-2014-10

Blodget, H. (2013, April 14). Amazon’s letter to shareholders should inspire every company in America. Business Insider. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.businessinsider.com/amazons-letter-to-shareholders-2013-4

Brown, M. (2014, July 25). Writers unite in campaign against ‘thuggish’ Amazon. The Guardian. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/jul/25/writers-campaign-amazon-ebook-dispute-us-hachette

Carroll, C. E. (Ed.). (2011). Corporate reputation and the news media: Agenda-setting within business news coverage in developed, emerging, and frontier markets. New York: Routledge.

Christ, M., & Sandor, R. (2015, July 23). Advice from two millennials on how business can do good. PRWeek. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.prweek.com/article/1357396/advice-two-millennials-businesses-good

Clark, M., & Young, A. (2013, December 18). Amazon: Nearly 20 years in business and it still doesn’t make money, but investors don’t seem to care. International Business Times. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.ibtimes.com/amazon-nearly-20-years-business-it-still-doesnt-make-money-investors-dont-seem-care-1513368

Cone Communications, & Echo Research. (2013). Cone Communications/Echo global CSR study. Boston, MA: Authors.

Del Rey, J. (2015, February 26). What Amazon’s hire of former Obama spokesman says about its PR machine. Re/code. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.recode.net/2015/2/26/11559480/what-amazons-hire-of-former-obama-spokesman-says-about-its-pr-machine

Demmitt, J. (2015, June 10). ‘Inclusion leads to growth’: Rev. Jesse Jackson calls on Amazon to work harder to improve diversity. Puget Sound Business Journal. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.bizjournals.com/seattle/blog/techflash/2015/06/inclusion-leads-to-growth-rev-jesse-jackson-calls.html

Dulaney, C. (2015, December 31). 5 best performers in the S&P 500 in 2015. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://blogs.wsj.com/briefly/2015/12/31/5-best-performers-in-the-sp-500-in-2015/

Feldman, G. (2014, May 30). BEA: Hachette/Amazon dispute ‘will change publishing.’ TheBookseller.com. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.thebookseller.com/news/bea-hachetteamazon-dispute-will-change-publishing

Flynn, K. (2015, October 22). Amazon (AMZN) Q3 2015 earnings: $25.4 billion revenue beats estimates, Jeff Bezos touts Amazon Fire. International Business Times. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.ibtimes.com/amazon-amzn-q3-2015-earnings-254-billion-revenue-beats-estimates-jeff-bezos-touts-2152854

Foer, F. (2014, October 9). Amazon must be stopped. The New Republic. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from https://newrepublic.com/article/119769/amazons-monopoly-must-be-broken-radical-plan-tech-giant

Freeman, R. E. (2010). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Freeman, R. E., Harrison, J. S., & Wicks, A. C. (2007). Managing for stakeholders: Survival, reputation, and success. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Global consumers are willing to put their money where their heart is when it comes to goods and services from companies committed to social responsibility [Press release]. (2014, June 17). Nielsen. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.nielsen.com/content/corporate/us/en/press-room/2014/global-consumers-are-willing-to-put-their-money-where-their-heart-is.html

Global publishing leaders 2015: Hachette Livre. (2015, June 26). Publishers Weekly. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/publisher-news/article/66975-global-publishing-leaders-2015-hachette-livre.html

Greene, J. (2015, June 9). Jesse Jackson to press for more inclusion in Amazon workplace. Seattle Times. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.seattletimes.com/business/amazon/jesse-jackson-to-press-for-inclusion-in-amazon-workplace

Greenfield, J. (2014a, January 31). Amazon revenues huge, profits tiny in 2013. DigitalBookWorld.com. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.digitalbookworld.com/2014/amazon-revenues-huge-profits-tiny-in-2013

Greenfield, J. (2014b, May 28). How the Amazon-Hachette fight could shape the future of ideas. The Atlantic. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/05/how-the-amazon-hachette-fight-could-shape-the-future-of-ideas/371756

Hachette rebuffs Amazon bid. (2014, May 28). Investor’s Business Daily. Retrieved July 21, 2015, from http://news.investors.com/052814-702507-hachette-rebuffs-amazon-bid.htm

Hanauer, N. (2015, November 25). The real reason Wal-Mart’s profits are hurting. U.S. News and World Report, online. Retrieved on August 18, 2016 at http://www.usnews.com/opinion/economic-intelligence/2015/11/25/the-real-reason-wal-marts-profits-are-hurting

Hern, A. (2015, June 22). Pay-per-page: Amazon to align payment with how much customers read. The Guardian. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2015/jun/22/amazon-kindle-payment-how-much-customers-read

Hof, R. (2004, August 1). Online extra: Jeff Bezos on word-of-mouth power. Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2004-08-01/online-extra-jeff-bezos-on-word-of-mouth-power

Kantor, J., & Streitfeld, D. (2015, August 15). Inside Amazon.com: Wrestling big ideas in a bruising workplace. New York Times. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/16/technology/inside-amazon-wrestling-big-ideas-in-a-bruising-workplace.html?_r=0

Kozlowski, M. (2014, June 12). Hachette derives 60% of ebook revenue from Amazon. GoodeReader.com. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://goodereader.com/blog/e-book-news/hachette-derives-60-of-ebook-revenue-from-amazon

Krugman, P. (2014, October 19). Amazon’s monopsony is not o.k. The New York Times. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/20/opinion/paul-krugman-amazons-monopsony-is-not-ok.html?smid=tw-share&_r=0

Lashinsky, A. (2014, May 27). In the standoff between Amazon and Hachette, the customer comes last. FORTUNE. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://fortune.com/2014/05/27/in-the-standoff-between-amazon-and-hachette-the-customer-comes-last

Leadership principles. (n.d.). Amazon.com. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.amazon.jobs/principles

Letter to Amazon.com, Inc. board of directors. (2014, September 19). AuthorsUnited.net. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://authorsunited.net

Mahler, J. (2014, November 9). Cubicles rise in a brave new world of publishing. The New York Times. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/10/business/cubicles-rise-in-brave-new-world-of-publishing.html?_r=1

McGee, S. (2014, November 16). Amazon vs. Hachette: The battle is over, the war isn’t. The Fiscal Times. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.thefiscaltimes.com/Columns/2014/11/16/Amazon-vs-Hachette-Battle-Over-War-Isn-t

A message from the Amazon books team. (n.d.). ReadersUnited.com. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.readersunited.com

Miller, L. (2014, August 20). Amazon’s awful war of words: How an iron-fisted PR strategy went off the rails. Salon.com. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.salon.com/2014/08/20/amazons_awful_war_of_words_how_an_iron_fisted_pr_strategy_went_off_the_rails

Milliot, J. (2014, May 28). BEA 2014: Can anyone compete with Amazon? Publishers Weekly. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/bea/article/62520-bea-2014-can-anyone-compete-with-amazon.html

Musil, S. (2012, April 11). DOJ files e-book price-fixing suit against Apple. CBS News. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.cbsnews.com/news/doj-files-e-book-price-fixing-suit-against-apple

Over 900 authors sign open letter to Amazon. (2014, August 6). Publishers Weekly. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/digital/retailing/article/63591-over-900-authors-sign-open-letter-to-amazon.html

Overview. (n.d.). Amazon.com. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://phx.corporate-ir.net/phoenix.zhtml?c=176060&p=irol-mediaKit

Plowman, K. L., & Rawlins, B. L. (2010). Prioritizing stakeholders for public relations: A case study of evidence. In T. McCorkindale (Ed.), Proceedings of the Public Relations Society of America Educators Academy (pp. 195-212). Washington, DC: Public Relations Society of America.

Posadas, D. (2016, January 25). How Amazon is changing the book publishing business. EJInsight.com. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.ejinsight.com/20160122-how-amazon-is-changing-the-book-publishing-business

PricewaterhouseCoopers. (2015). Global top 100 companies by market capitalisation: 31 March update. London: Author.

Quinn, A. (2014, July 21). Book news: ‘Big 5’ publishers absent from Amazon’s new e-book service. NPR.org. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2014/07/21/333549534/book-news-big-5-publishers-absent-from-amazon-s-new-e-book-service

Ragas, M. W., & Culp, R. (2014). Business essentials for strategic communicators: Creating shared value for the organization and its stakeholders. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Rawlins, B. L. (2006). Prioritizing stakeholders for public relations. Gainesville, FL: Institute for Public Relations.

Reeves, J. (2015, October 26). Amazon is now an unstoppable stock. MarketWatch.com. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.marketwatch.com/story/amazon-is-now-an-unstoppable-stock-2015-10-26

Regional grocer Wegmans unseats Amazon to claim top corporate reputation ranking. (2015, February 4). The Harris Poll. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.theharrispoll.com/business/Regional-Grocer-Wegmans-Unseats-Amazon.html

Reputation Institute. (2014). Global RepTrak 100: The world’s most reputable companies: A reputation study with consumers in 15 countries. New York: Author.

Solomon, B. (2012, May 9). Billionaires’ tips for new grads: Advice from Jobs, Oprah, Zuckerberg and more. Forbes.com. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.forbes.com/sites/briansolomon/2012/05/09/billionaires-advice-for-new-college-graduates-jobs-oprah-zuckerberg-and-more/2/#620e67ae2a4f

Spiro, J. (2009, October 23). The great leaders series: Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon.com. Inc. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.inc.com/30years/articles/jeff-bezos.html

Statista.com (2016, January). Monthly unique visitors to U.S. retail websites. Retrieved on August 18, 2016, from http://www.statista.com/statistics/271450/monthly-unique-visitors-to-us-retail-websites

Stone, B. (2011, September 28). Amazon, the company that ate the world. Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2011-09-28/amazon-the-company-that-ate-the-world

Stone, B. (2013). The everything store: Jeff Bezos and the age of Amazon. New York: Little Brown & Company.

Stone, B., & Rich, M. (2010, January 30). Amazon removes Macmillan books. The New York Times. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/30/technology/30amazon.html

Streitfeld, D. (2014, 7 August). Plot thickens as 900 writers battle Amazon. The New York Times. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/08/business/media/plot-thickens-as-900-writers-battle-amazon.html

Streitfeld, D. (2015a, February 26). Amazon hires Jay Carney, former Obama press secretary. The New York Times. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from www.nytimes.com/2015/02/27/technology/amazon-hires-jay-carney-former-obama-press-secretary.html

Streitfeld, D. (2015b, July 13). Accusing Amazon of antitrust violations, authors and booksellers demand inquiry. The New York Times. Retrieved August 8, 2016, from www.nytimes.com/2015/07/14/technology/accusing-amazon-of-antitrust-violations-authors-and-booksellers-demand-us-inquiry.html

Streitfield, D., & Scott, M. (2015c, June 11). Amazon’s e-books business investigated by European antitrust regulators. The New York Times. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from www.nytimes.com/2015/06/12/business/international/european-union-amazon-ebooks-antitrust-investigation.html

Trachtenberg, J. (2014, July 29). Amazon calls for Hachette to cut e-brook prices. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.wsj.com/articles/amazon-calls-for-hachette-to-cut-e-book-prices-1406675179

Trachtenberg, J. (2015, June 22). Amazon, Penguin Random House agree to new deal on book sales. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.wsj.com/articles/amazon-penguin-random-house-agree-to-new-deal-on-book-sales-1434644767

Wulfraat, M. (n.d.). Amazon global fulfillment center network. MWPVL International. Retrieved August 18, 2016, from http://www.mwpvl.com/html/amazon_com.html

YCharts.com. (2016, February 29). Amazon.com market cap. Retrieved February 29, 2016, from http://ycharts.com/companies/AMZN/market_cap

KELSEY DIMAR, M.A., is a marketing content strategist at Liquor Stores N.A. She graduated from DePaul University in 2015 with an M.A. in public relations and advertising.

RACHEL ANN KUCHAR wrote and published this paper as part of her studies at DePaul University while receiving her Master of Arts in public relations and advertising. She works for Weber Shandwick’s healthcare practice in Chicago. Email: RKuchar[at]webershandwick.com.

MATTHEW W. RAGAS, Ph.D., is an associate professor and academic director of the public relations and advertising graduate program in the College of Communication at DePaul University. He earned his Ph.D. from the University of Florida. Email: mragas[at]depaul.edu.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the dedication, enthusiasm, and spirit of inquiry among the students in the Fall 2014-2015 Corporate Communication graduate seminar at DePaul University. This course inspired the initial development of this case study, as well as several winning entries into the 2015 Arthur W. Page Society case study competition in corporate communication.

Editorial history

Received August 5, 2015

Revised March 10, 2016

Accepted May 17, 2016

Published August 26, 2016

Handled by editor; no conflicts of interest