To cite this article

Grantham, S. (2015). Power to the people: CL&P’s crisis communication response following the 2011 October nor’easter. Case Studies in Strategic Communication, 4, article 2. Available online: http://cssc.uscannenberg.org/cases/v4/v4art2

Access the PDF version of this article

Power to the People: CL&P’s Crisis Communication Response Following the 2011 October Nor’easter

Susan Grantham

University of Hartford

Abstract

This case highlights the need for strategic crisis communication planning when employing the public information model of communication following a natural disaster. In October 2011, a nor’easter hit the state of Connecticut and resulted in the majority of residents losing power for an extended period of time. Following the storm, stakeholders perceived messaging from Connecticut Light & Power (CL&P), the major utility company, about the restoration timeline as lacking credibility. Subsequent investigations revealed that the actual restoration work was indeed conducted in a timely and professional manner. However, the poor communication throughout the restoration timeline damaged CL&P’s reputation, resulted in CL&P’s CEO and President Jeffrey Butler resigning from his position, and subsequent changes in crisis communication planning within CL&P.

Keywords: crisis communication; credibility; strategic planning

Introduction

Before a crisis occurs, organizations need to have strategic plans in place in order to communicate effectively. The first priority for an organization following a crisis is to protect stakeholders from harm (Coombs, 2007c). Consideration of the organization’s reputation is secondary. However, research has shown that crises types, and response actions to those crises, will ultimately influence stakeholders’ opinions and attitudes toward an organization following a crisis event.

In October 2011, an early snowstorm hit much of the New England area resulting in massive power outages for an extended period of time. Over 800,000 homes and businesses lost power in Connecticut. This case study examines the effectiveness of Connecticut Light & Power’s (CL&P) crisis communication following the storm using Coombs’ (2007c) Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT). SCCT provides a framework for categorizing types of crises and the perceived level of responsibility for the crisis stakeholders attribute to the organization.

This case is based on information available from the National Weather Service, post-storm reports commissioned by the Governor’s office (McGee & Skiff, 2012; Witt Associates, 2011), CL&P’s own report (Davies Consulting, 2012), media archives, conversations with communication personnel at CL&P, and the author’s personal experience following the October storm in 2011.

The key finding from this research documents that CL&P’s technical response for assessing damage and restoring power was reasonable (Davies Consulting, 2012). However, the investigative reports specify that CL&P failed to educate and inform stakeholders about the damage assessment and restoration process resulting in a negative backlash against CL&P and its spokesperson, CEO and President, Jeffrey Butler.

Background

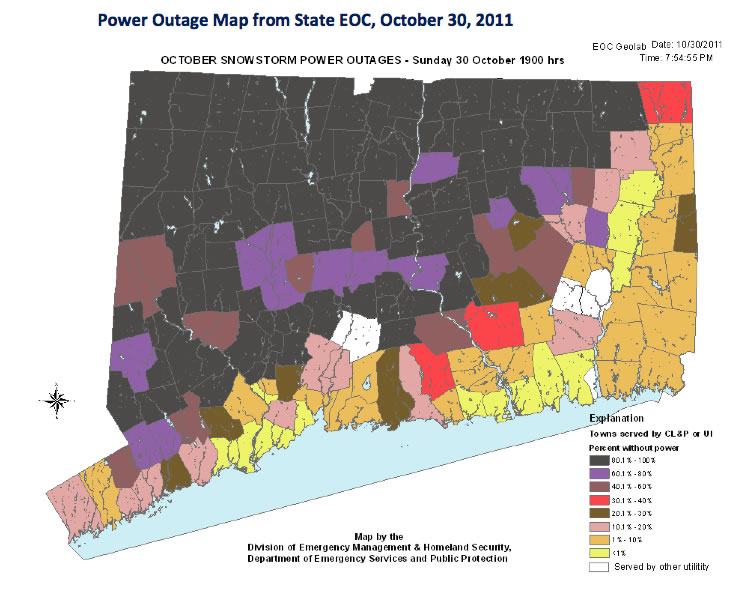

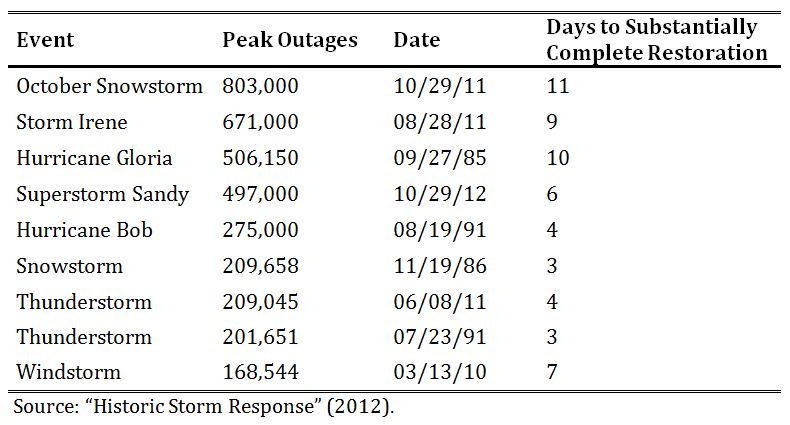

Two major weather events occurred in the state of Connecticut in 2011. Hurricane Irene came onshore on August 28, and the October Nor’easter hit on October 29. Both storms left a large portion of the state’s residents without power. The October Nor’easter caused the largest number of power outages to residents in the state’s history (see Figure 1 and Table 1).

Figure 1. Screen shot of outage map on November 3, 2011, four days after the October Nor’easter (Witt Associates, 2011, p. 19). Table 1. Significant CL&P storm outages.In the days leading up to the October Nor’easter, weather forecasts for an extreme storm were the focus of many news broadcasts. The forecasts predicted between 6-7 inches of heavy and wet snow, which could cause major damage due to the foliage still on the trees. Connecticut’s Governor Dannel P. Malloy encouraged residents to be prepared to be without power for an extended period of time. The snowstorm, a natural disaster, caused damage resulting in power outages to the majority of Connecticut’s residents.

Following the October Nor’easter, CL&P, the state’s major utility company, along with the Governor’s office, was immediately in the hot seat as to when power would be restored. While the daytime temperatures were moderately cool in the mid-50’s, the night time temperatures were dropping to near freezing or freezing. Residents did not know how long to plan to be without lights and heat or whether to stay at home or go somewhere else. Customers were ‘aroused’ publics who had low knowledge about how soon the power would be restored and who were highly interested in when that would take place (Hallahan, 2001). Residents were information-seeking (Grunig, 1997) but information was basically limited to daily media briefings held at the emergency operation center. The primary channels of information were radio broadcasts and newspapers. In terms of external communications, CL&P’s website did not provide current information, even for those who had Internet access, nor did CL&P utilize their social media channels effectively.

Connecticut, like most states, has a plan for communicating with stakeholders during a time of emergency called a State Response Framework (SRF) (Department of Emergency Services and Public Protection [DESPP], 2011). The state government has the responsibility to coordinate with federal and local government entities, state agencies, private sector partners, the media and the public in “implementing emergency response and recovery functions in times of crisis” (DESPP, 2011, p.1). Under this plan, the state’s two utility companies worked with officials “to prepare and deliver coordinated and sustained messages to the public in response to emergencies within the State of Connecticut” (DESPP, 2011, p.33). Via the Emergency Operations Center, Governor Malloy and CL&P informed various stakeholders, including residents and local town managers, about the progress being made to restore power in twice-daily news briefings (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Governor Dannel Malloy (left) and Jeffrey Butler, CL&P CEO and President, at one of the twice-daily news briefings. Click the screen shot to view a sample of one of the news briefings from November 2, 2011.CL&P, a subsidiary of Northeast Utilities, has been a provider of electricity in Connecticut since 1917 (“CL&P History,” 2013). CL&P is Connecticut’s largest electric utility, serving more than 1.1 million customers. CL&P serves residential, municipal, commercial and industrial customers in 149 of Connecticut’s 169 cities and towns.

Stakeholders

Due to the massive damage caused by the storm, almost everyone was without power and therefore a stakeholder. Even if a homeowner had power, where they worked may have been without power or the local schools may have been closed.

CL&P employees needed information as they responded to residents’ inquiries and also in their role as liaisons to town managers. Town managers were in need of timely information in order to make decisions about establishing and keeping open emergency shelters and schools, as well as continuing to host other town activities (e.g., elections, Halloween festivities/events).

Emergency management teams at the state and local levels needed information to coordinate personnel to support at-risk facilities such as hospitals and nursing homes.

State agencies such as the Department of Transportation needed to be able to prioritize roadwork to clear major interstates and traffic arteries of debris and downed power poles and lines.

The media, as the primary conduit of information, needed current information as they broadcast the news briefings on the radio and television as well as reproduced maps and other relevant information in print.

Primary Communicators

Governor Dannel P. Malloy

Dannel P. Malloy was serving in his first year as Connecticut’s governor. On the day prior to the storm Governor Malloy set up the Emergency Operations Center in the State Armory. The governor’s office warned the state’s residents to be prepared to lose power.

News briefings began on Sunday, October 30, 2011, as the storm concluded and Governor Malloy declared a state of emergency (Forer, Tanglao & Schabner, 2011).

CL&P President and CEO – Jeffrey Butler

CL&P initially used a spokesperson whose typical responsibilities fell in the technical public relations role position (Broom & Dozier, 1986). However, within days, Jeffrey Butler, CL&P’s president and CEO, assumed the spokesperson duties as he could answer technical questions and his role was to supervise the overall restoration effort.

CL&P’s Town Liaison Personnel

Prior to the October Nor’easter CL&P assigned liaisons to each town. Unlike many parts of the country where there are countywide systems, Connecticut has 169 towns, each with its own council, mayor, town manager, emergency response departments, and school system. CL&P assigned 101 town liaisons to the 149 affected towns (some liaisons served two towns).

Town Managers and Selectmen/Mayors

Elected and appointed officials in each town had a responsibility to allocate resources and communicate with the residents in town. Eventually, some towns went to a phone system for those with a landline to update the residents about the progress in town, the location of emergency shelters, and areas of town to avoid due to remaining debris and downed wires.

Strategies and Tactics

Communication for this event is comprised of the pre- and post-storm stages.

Pre-storm Communication Objective – Storm Preparation by Connecticut Residents

Prior to the storm, the Governor authorized the opening of the Emergency Operations Center (EOC). The role of the EOC was to provide a central location to collect and distribute relevant information to stakeholders. Before the storm, CL&P began planning for post-storm damage assessment, allocation of restoration personnel and equipment, requests for assistance from other utilities, and they operationalized their town liaisons. Media outlets broadcasted and published the weather warnings from the National Weather Service.

Post-storm Communication Objective – Human Safety, Damage Assessment and Power Restoration

The storm deposited between 8-12 inches of snow and ice throughout the state, more than predicted, and the damage was excessive. At the conclusion of the storm the Governor declared a state of emergency and daily news briefings began from the Emergency Operations Center (EOC) located at the State Armory in Hartford, Connecticut. CL&P provided updated information at the news briefings about damage assessment, safety guidelines, responsibilities of homeowners, progress on obtaining assistance from outside utility companies, and other restoration information. CL&P’s employee town liaisons were operationalized and local media began relating information. Television and radio stations outlets broadcast the news briefings live.

Initially, CL&P provided a spokesperson to report on CL&P’s damage assessment progress and restoration timeline at the news briefings at the EMC. CL&P’s president and CEO Jeffrey Butler quickly replaced the initial spokesperson because he had more technical expertise and management knowledge of CL&P’s damage assessment and power restoration activities. Along with the live broadcasts of the briefings, newspapers printed articles detailing the content covered in the briefings along with human-interest stories. Neither social media nor the Internet where utilized very much by anyone.

CL&P and the Governor’s Office used the daily news briefings to update most stakeholders and ultimately relied on traditional media outlets to distribute the information (see Appendix for communication timeline and messages). Most residents did not have access to television but they could at least listen to the briefings with a battery-powered radio or in their cars. Newspapers provided more in-depth coverage and printed the maps provided by CL&P of the restoration efforts (see Figure 1).

Many residents had limited access to the Internet and finding information on line was onerous, slow going, nonexistent and not updated in a timely manner. The outage maps were not available on the CL&P website or through the state government’s emergency 211 website until several days had passed.

CL&P employees who served as liaisons to the town managers distributed information to town managers based on reports from the field. However, there was no system in place to transmit information in real time. The reports literally had to be taken back to CL&P’s headquarters and shared with the management team and town liaisons. Consequently, anything the town liaisons may have been communicating about could be outdated information by the time it was relayed to the town managers.

In the immediate aftermath of the storm, the Governor and CL&P spokesperson were speaking with ‘one voice’ (Coombs, 2007c) in terms of safety precautions and the extensive nature of the damage from the EOC. The ‘one voice’ method of communication allows for the distribution of accurate information across a range or organizations with a vested interest in the crisis (Coombs, 2007a). However, that soon changed and the Governor separated himself from CL&P’s CEO, Jeffrey Butler, resulting in CL&P becoming the scapegoat for the perceived mismanaged and delayed restoration of power to residents.

Evaluation

The occurrence of a crisis has the potential to damage an organization’s reputation. Consequently, post-crisis communication is pivotal in protecting an organization’s reputation (Coombs & Holladay, 2001). Just who is responsible for the crisis management is sometimes unclear and those who are impacted seek information to understand the crisis, its implications and to attribute blame (Brown & White, 2011). Subsequently, if an organization is unprepared to proactively communicate about the crisis, stakeholders may attribute more blame to the organization than they should and an organization’s reputation may become diminished.

Coombs’ (2007c) Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) provides a framework for practitioners to understand crises types and to prepare communication strategies that apply to these crises. Coombs (2007c) established crisis types by crisis clusters: victim, accidental and preventable (p. 168). Victim crises (natural disaster, rumor, workplace violence, product tampering) occur when an organization is also perceived to be a victim of the crisis. There is a weak attribution of crisis responsibility with a mild reputational threat. The accidental cluster (challenges, technical error accidents, technical error – product harm) indicates that the organization is responsible for the crisis but its actions were unintentional. This type of crisis results in a minimal attribution of responsibility and a moderate threat to reputation. The preventable cluster (human error accidents, human error-product harm, organizational misdeed with no injuries, organizational misdeed management misconduct, organizational misdeed with injuries) results in a strong attribution of responsibility and a severe threat to reputation.

CL&P entered the aftermath of the October Nor’easter crisis as a victim. The cause of the crisis was the weather: a natural disaster. CL&P was not responsible for the storm and warnings had gone out to be prepared to be without power for several days before the storm from the Governor’s office and through the local news and weather alerts. However, within days of the storm having hit the area, stakeholders became disillusioned with CL&P’s restoration efforts and perceived lack of communication about these efforts. Timely information was difficult to obtain and thus residents did not know how to plan or respond to their current situation because they really did not know how long the situation would last. CL&P’s crisis moved from the victim cluster (natural disaster) to the preventable cluster (organizational misdeed with injuries). What did CL&P do wrong? Nothing and everything.

Stakeholders recognized that CL&P was not responsible for the weather. However, the lack of information from CL&P following the storm about the damage assessment process and the amount of time and effort it takes to clear areas to ultimately restore power, along with the knowledge that there were on-going injuries and deaths from people improperly trying to heat their home using grills inside the home, generators without proper ventilation, and more, helped shift the public’s perception of how CL&P was handling the restoration.

By the third day following the storm the town managers were vocally dissatisfied with their ability to obtain realistic information from their CL&P designated town liaison. The negative perceptions were further perpetuated by the change in the Governor’s behavior at the daily news briefings on the fourth day following the storm (see Appendix). Until that point, the media briefings had an established pattern where Governor Malloy typically provided an overview of the situation, pertinent phone numbers, and other basic information, and then turned the briefing over to Jeffrey Butler. Following Butler’s report, the Governor then spoke again and he always remained while Butler spoke. On the fourth day following the storm, Governor Malloy gave his usual overview and then left the room. The media and others interpreted this behavior as a loss of faith in Butler and CL&P and they reported the behavior as such. Six days after the storm the Governor begins openly challenging Butler and dismissing Butler’s reports about the restoration work as being unrealistic. The media began focusing on the negative perceptions and attitudes by the town managers and the governor as residents and other stakeholders remained uninformed about the restoration timeline. In this situation, information-seeking individuals (Grunig, 1997) lacked their usual resources in obtaining any information and relied heavily on the media. As noted previously, none of the primary communicators utilized social media or the Internet effectively.

Analysis and Discussion

The public information model of communication was used to communicate about assessment and restoration efforts to the general public (Grunig & Hunt, 1984). The public information model is a one-way communication model used to distribute factual content to the public and is often used in emergency management systems.

Of the impacted publics, CL&P’s customers comprised the vast majority of residents and business owners who lost their power. Simply put, the loss of power complicated the ability of CL&P to assess the damage, collect and report information in real time, and subsequently communicate about restoration efforts to the various stakeholder groups. Government officials and residents had little access to information beyond the media briefings that they could listen to in the form of radio broadcasts or read about in the newspapers. During the briefings, those listening to the radio (because they could not watch the briefings on TV) had no way to see the maps that were being referred to and the newspapers content containing the maps was outdated information by the time it was published. Neither the EOC nor CL&P utilized social media or the Internet effectively in first the days following the storm.

Within a week, public opinion had crystallized (Van Leuven & Slater, 1991), and CL&P’s restoration efforts were perceived as being insufficient and ineffective. It is at this stage that stakeholders are aware of the issue, have processed their thoughts on the issue and reached a decision. It is also at this stage that the media plays a pivotal role by providing the feedback to the various stakeholders and primary participants how the public is siding on an issue (Van Leuven & Slater, 1991, p. 174). In this case, the media was focusing on how dissatisfied residents and town managers were about the restoration efforts.

A primary issue is that Connecticut’s residents had no prior experience with this type of storm. There was no framework or historical experience against which stakeholders could assess CL&P’s activities. While everyone had been pre-warned to be without power for some time, the vagueness of the restoration timeline was disconcerting. The perception that the flow of information from CL&P was delayed and erroneous grew. The Governor and the media quickly targeted CL&P as inefficient and ineffective. This case highlights how to communicate about this type of crisis.

First, as the president, Butler should have been overseeing the damage assessment and restoration efforts instead of spending hours each day traveling to the EOC to provide updates at the news briefings. The spokesperson responsibility should have been assigned to someone else who could cogently communicate the desired information to the various stakeholders.

Soon after the storm passed CL&P and Governor Malloy were not viewed as speaking with ‘one voice’. The lack of the ‘one voice’ perspective was brought up in all three summary reports following the October Nor’easter (Davies Consulting, 2012; McGee & Skiff, 2012; Witt Associates, 2011). A specific recommendation stated, “CL&P corporate communications and emergency preparedness and response should designate qualified and trained individuals, who have an understanding of but do not have other immediate operational roles, to serve as public spokespersons for the company in power restoration and other emergency incidents” (Witt Associates, 2011, p. 23). The Davies Consulting (2012) report stated, ‘The communications group worked hard to keep the public informed; however, CL&P failed to utilize a “one voice” approach” (p. 56).

Second, Butler failed to communicate what was a reasonable time frame for damage assessment to the stakeholders groups before specific plans could be made to restore power. Stakeholders simply did not understand the process involved. During the initial stages of recovery, CL&P appeared to be reactive instead of proactive. Residents, and even government officials, are not schooled in utility technology. Much like running water, it is just there until it is not. As a state, Connecticut does not suffer from many adverse weather issues and therefore most residents lack a history or experience in dealing with the fall-out from such weather events. Delays in getting extra utility assistance to the state and in calling out the National Guard to assist in debris removal should have been planned and communicated about much earlier than what actually took place.

Clearly safety was the priority issue for all stakeholder groups but the idea of just what safety constituted varied. For CL&P, it was important to assess the damage, remove live wires, prevent fires, keep their personnel from being shocked from power surges by improperly installed whole-house generators, and so on. Town managers, emergency staff, and hospitals needed to know how long they would need to rely on generators and if they needed to move patients. Residents wanted to know if they could get out of their homes and neighborhoods (many could not) and if they should stay or go due to the low overnight temperatures and the potential of pipes freezing and bursting. Restoration efforts were well underway before location specific information was available.

Third, Butler made some comments that the Governor, and media, focused on that detracted from his credibility. For example, Butler said on November 3, 2011, that the severity of the storm came as a surprise. Weather forecasters immediately pushed back claiming that they had predicted the storms arrival time, potential snowfall and potential damage throughout the week leading up to the storm. Later that day Butler recanted his earlier assertion, “I misspoke, he said referring to his comments earlier in the day. The days have been running together” (Green, 2011, para. 4). Butler’s prediction that 99 percent of residents would have their power restored by November 6, 2011 was not vetted internally and while fairly accurate, this information did not have the support of CL&P’s employees, especially among the employees serving as town liaisons, because they too lacked information.

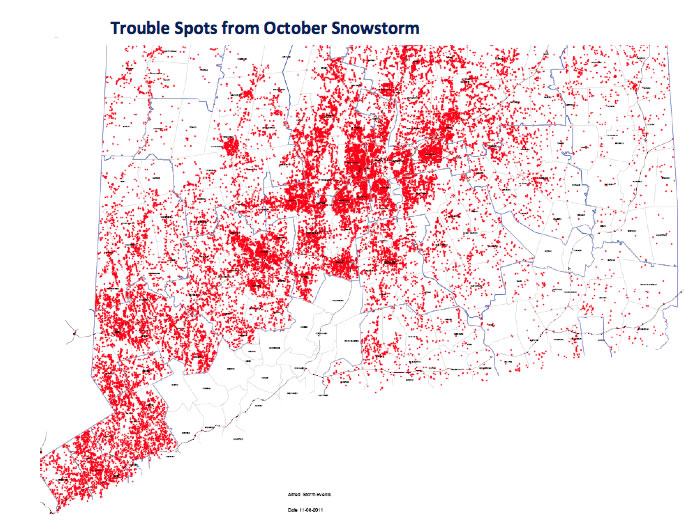

Fourth, Butler did not do a good job describing which 99 percent of the residents would have power by Sunday, November 6, 2011. Butler failed to explain that CL&P was strategically restoring power to the largest contingency of residents first. Residents living in the towns with the worst damage would likely have their power restored last as this is where the majority of trouble spots dealing with transmissions lines were located (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Screen shot taken from Witt Associates report (2011, p. 9) of the ‘trouble spots’ that are centralized in the north central part of the state and from where most of the complaints from town managers came.Fifth, no person in CL&P appeared to have the technical expertise and sufficient media training to deal with the required communication demands. Butler was not prepared to take over these duties and he seemed to lack confidence in providing explanations and was unable to push back against unreasonable demands for specific deadlines and other information. Butler’s methodical delivery of information, and defense of what CL&P was doing at any given time, led to the Governor, media and affected residents in losing faith in CL&P’s message.

Following the storm, various town managers, selectmen and mayors were frustrated by the lack of information they received from CL&P even though each town had been assigned a liaison (Falcone, 2011). Town managers were not educated about the two types of assessment CL&P conducted. The first type of damage assessment provides information about how many residents and businesses are without power – or the ‘what’ of the situation. The second type of assessment focuses on the reasons for the power outages – or the ‘why.’ The ‘why’ part of the situation drives restoration planning, whether it be from blown transformers, transmission lines, or downed wires. It takes time to compile this information and subsequently develop restoration plans. Thus, a reasonable timeline for restoration can seem to take longer than necessary if you don’t understand the process. Additionally, information about securing outside utility restoration help and where these resources would be deployed is a fluid situation and can be difficult to communicate about accurately.

Due to the lack of any real new information during the twice-daily news briefings, the media soon began focusing on peripheral issues. By November 7, nine days after the storm, Governor Malloy, ordered an investigation into CL&P’s readiness practices, declaring that there was possible malfeasance by the company (Lender, 2011). CL&P’s messenger, in the form of Butler, had become the scapegoat.

Jeffrey Butler had been CL&P’s President for just over two years when the October Nor’easter hit the state. With over 30 years experience in the energy business, Butler’s engineering knowledge and exposure to a broad range of energy related issues and management experience made him a logical choice to head up CL&P and serve as its president. However, Butler lacked expertise in dealing with the media in a crisis. “Twice a day, Butler walks to the podium in the Emergency Operations Center at the State Armory in Hartford and grimly faces skeptical reporters who out-shout each other for the chance to challenge the company’s restoration projections” (Kauffman, 2011 para.7). Ultimately, Butler resigned from his position on November 17, 2011, less than three weeks after the storm, but not before everyone’s power had been restored. While there was no specific call for Butler to resign, he thought if he remained as the CEO and president of CL&P it would be a challenge for the company (Lender & Keating, 2011, para.7).

Following the October Nor’easter, three investigative reports were generated assessing, in part, CL&P’s performance. The investigative report initiated by Governor Malloy was released on December 1, 2011 (Witt Associates, 2011). Another of the reports, the Two Storm Panel Report, was already underway to assess the response to Hurricane Irene and was released on January 29, 2012. The third report, an internal investigation by CL&P, was submitted on February 27, 2012 (Davies Consulting, 2012).

All three reports emphasized a need for better planning (staffing to scale of event), improved internal and external communications, and the need to speak with ‘one voice’ across agencies. In response to the December 1, 2011 Witt Associates report, Northeast Utilities (CL&P’s parent company) stated, “We know we let our customers down and especially the towns down by not being able to give them enough information to prepare for their shelters to prepare for their own services” (Stuart & McQuaid, 2011, para. 36).

The three reports also had positive things to say about the CL&P performance. There were no injuries or deaths related to repairing the power grid and lines.

Lessons Learned

This case highlights the need for strategic planning and communication prior to a crisis. First, when using the public information model of communication following a natural disaster, it is necessary to have had two-way communication with stakeholders prior to the event in order to establish understanding about the post-crisis process. This prior communication will lead key participants to speak with ‘one voice’ and create a collaborative problem-solving approach. CL&P’s restoration predictions were accurate but they lacked of credibility because Butler did not handle the media well which is crucial (Coombs, 2007b). The apparent loss of confidence by Governor Malloy in Butler’s reports compounded the credibility issue and became a focus of media attention.

Following this event CL&P appointed a Vice President to speak on behalf of the company, which serves two purposes. First, this person is media trained and technically informed so that the information that s/he shares is provided in a way that is useful to emergency management personnel and the public. Second, having an appointed spokesperson to deal with large power outage events frees the CEO to oversee restoration efforts more effectively as s/he is now not distracted by having to attend news briefings.

Second, CL&P’s town liaisons need to be prepared to communicate effectively with the town managers. This requires internal and external communication training. A central plan needs to be in place to update liaisons who communicate with the town managers who can then communicate with the town’s residents. Additionally, liaisons need to be familiar with the needs of their assigned towns.

CL&P has developed a community relations’ team that now works full-time with the 149 towns CL&P has responsibility for. The teams have been trained to communicate relevant information and the utility has upgraded its technology to relay reports from the field about assessment and repair work so that the community relations’ personnel have the information in real time; something that was missing during the October Nor’easter.

Third, direct-to-consumer information channels need to be established. Since the October Nor’easter, CL&P has upgraded its field systems and can now cut damage assessment time by one-third (Turmelle, 2013). This information can be communicated to residents who sign up for text alerts. Residents can sign up for information for more than one town, which may help residents seeking information for others such as older parents who live nearby but who may not use text messaging. Additionally, CL&P has expanded its social media presences, and interaction, on Facebook and Twitter so that customers can use these networks to communicate with the utility and get information.

CL&P has also taken the additional step of providing ‘events in the field’ following major power outages where media personnel can go to the site and get local information to share with viewers, listeners and readers. This strategy also allows CL&P to have a spokesperson to address local issues instead of the statewide approach that was used following the October Nor’easter.

Additionally, in conjunction with other utility entities through the mutual aid systems, CL&P has realigned its access to resources and its ability to pull assistance in from other areas regionally as well as provide assistance to other impacted areas.

Furthermore, CL&P, in conjunction with other community partners in the Connecticut Conference of Municipalities, has undertaken a program to educate the community partners about what CL&P does before, during and after a storm and the steps that are involved at each stage so that the community partners have a clearer idea of what to expect. CL&P has also worked to provide a better-coordinated response with emergency responders, state emergency personnel and Homeland Security by participating in drills and reviews.

Conclusion

CL&P became the target of scorn and disillusionment following the October Nor’easter resulting in a diminished organizational reputation. The Governor requested an investigation of CL&P’s preparation for the storm and actions following the storm. CL&P also commissioned its own investigation. Overwhelmingly the reports absolved CL&P of any wrongdoing or unprofessional behavior. However, all the reports indicated that CL&P had not communicated well during this time. Subsequently, CL&P initiated specific policies and practices to improve their ability to communicate with and inform key stakeholders from the Governor, to town managers to the public. These policies included educating key stakeholders about the process so there is now a greater understanding by everyone about what is actually involved.

CL&P had an opportunity to test these changes the following year in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, which prompted another partial activation of state’s Emergency Operation Center on October 26, 2012. The State of Connecticut’s Public Utility Regulation Authority report (Caron, House & Betkoski, III, 2013) states “the utilities performed their storm-related activities in a timely and effective manner” (p. 54) and, “the Authority concludes that CL&P has made significant improvements in communications both pre-storm and during restoration” (p. 7).

This case study demonstrates that being unprepared to communicate about a crisis can be just as bad as being unprepared to handle the physical crisis in terms of reputation management. In the months following the October Nor’easter, CL&P was exonerated regarding their technical execution of restoring power and CL&P has worked hard to improve their crisis communication abilities. In less than a year, based on its proactive approach to identifying and addressing crisis communication issues, CL&P had progressed from being the brunt of criticism from the government, the media and customers following the October Nor’easter to being reviewed as having made significant progress in its ability to manage relationships and information before, during and after a natural disaster following Hurricane Sandy which has lead to greater confidence in CL&P’s abilities by its stakeholders.

Activities

- Campuses are always vulnerable to a potential crisis situation. Go to http://ope.ed.gov/security and search for your institution.

- Pick one or two crimes the report provides statistics for.

- Determine which of Coombs’ (2007c) crisis categories (victim, accident, preventable) applies to the crimes you have selected.

- Specify key stakeholders who should know about this information in the event of an incident.

- Specify who should speak on behalf of your institution?

- Determine which channels should be used for this communication.

- Conduct a mock media interview session for the spokesperson identified as the key spokesperson in the activity one. Have one or two students function as the spokesperson who is responding to the media. Students should develop questions and act in the role of the media in a news briefing related to the crisis. Ask some questions that are off point.

- Conduct a debriefing about the spokesperson’s credibility, their knowledge of the incident and plans to safeguard against repeat incidents, and related factors.

- Name three things a spokesperson needs to have or know following a crisis in order to be an effective spokesperson.

References

Altimari, D. (2011, November 2). CL&P’s Butler said company prepared for outages, but the storm was ‘far more significant than what had been forecast.’ Hartford Courant. Retrieved July 1, 2015, from http://articles.courant.com/2011-11-02/news/hc-clpps-butler-said-company-prepared-for-outages-but-the-storm-was-far-more-significant-than-what-had-been-forecast-20111102_1_power-outages-weather-forecast-snow-storm

Broom, G. M., & Dozier, D. M. (1986). Advancement for public relations role models. Public Relations Review, 12(1), 37-56.

Brown, K. A. & White, C. L. (2011). Organization-public relationships and crisis response strategies: Impact on attribution of responsibility. Journal of Public Relations Research, 23(1), 75-92.

Caron, M. A., House, A. H., & Betkoski, J. W., III. (2013, August 21). PURA investigation into the performance of Connecticut’s electric distribution companies and gas companies in restoring service following storm Sandy – Decision (Docket no. 12-11-07). New Britain, CT: Public Utilities Regulatory Authority of Connecticut.

CL&P History: Beginnings of the Connecticut Light & Power Company. (2013). Connecticut Light & Power. Retrieved October 16, 2014, from http://www.cl-p.com/Home/AboutCLP/CLPHistory/CL_P_History/?MenuID=4294984959

Coombs, W. T. (2007a, October 30). Crisis management and communications. Institute for Public Relations. Retrieved July 1, 2015, from http://www.instituteforpr.org/topics/crisis-management-and-communications

Coombs, W. T. (2007b). Ongoing crisis communication: Planning, managing, and responding (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Coombs, W. T. (2007c). Protecting organization reputations during a crisis: The development and application of situational crisis communication theory. Corporate Reputation Review, 10(3), 163-176.

Coombs, W. T., & Holladay, S. J. (2001). An extended examination of the crisis situation: A fusion of the relational management and symbolic approaches. Journal of Public Relations Research, 13(4), 321-340.

Davies Consulting. (2012, February 27). Final report: Connecticut Light and Power’s emergency preparedness and response to Storm Irene and the October Nor’easter. Retrieved July 1, 2015, from http://daviescon.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/2012-02-NU-CLP-Irene-Oct-Nor’easter-Response.pdf

Department of Emergency Services and Public Protection (DESPP). (2011, August). State of Connecticut: State response framework (SRF). Retrieved July 1, 2015, from http://www.ct.gov/demhs/lib/demhs/ct_srf_aug_2011.pdf

Falcone, A. (2011, November 2). Municipal leaders’ frustrations rise as power lags. Hartford Courant. Retrieved from http://articles.courant.com/2011-11-02/news/hc-angry-municipal-leaders-1103-20111102_1_cl-p-van-winkle-town-officials

Forer, B., Tanglao, L., & Schabner, D. (2011, October 30). Snowstorm: Northeast cleans up after deadly nor’easter. ABC News: Good Morning America. Retrieved July 1, 2015, from http://abcnews.go.com/US/winter-storm-northeast-cleans-deadly-noreaster/story?id=14842621

Freak nor’easter storm blamed for 11 deaths. (2011, October 30). CBS News. Retrieved July 1, 2015, from http://www.cbsnews.com/news/freak-noreaster-storm-blamed-for-11-deaths

Gov. Malloy warns residents to prepare for power outages, emergency center to open on Saturday. (2011, October 29). The Independent. Retrieved October 16, 2014, from http://newhartfordplus.com/2011/10/29/winter-storm-warning-malloy-warns-residents-to-prepare-for-power-outages-opens-emergency-operations-center-saturday-afternoon

Governor calls in CT National Guard to help with storm recovery. (2011, November 3). Windham Today. Retrieved October 16, 2014, from http://windham.htnp.com/2011/11/03/governor-calls-in-ct-national-guard-to-help-with-storm-recovery/#sthash.onGVQTpY.dpuf(http://windham.htnp.com/2011/11/03/governor-calls-in-ct-national-guard-to-help-with-storm-recovery

Green, R. (2011, November 3). How could CL&P not know what we were in for? Hartford Courant. Retrieved July 1, 2015, from http://articles.courant.com/2011-11-03/news/hc-green-clp-weather-1103-20111102_1_wet-snow-national-weather-service-forecast

Grunig, J. E. (1997). A situational theory of publics: Conceptual history, recent challenges, and new research. In D. Moss, T. MacManus & D. Verčič (Eds.), Public relations research: An international perspective (pp. 3-48). London: International Thomson Business Press.

Grunig, J. E., & Hunt, T. (1984). Managing public relations. Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers.

Haigh, S. (2011, November 2). Power restoration continues, Malloy says not fast enough. CBS Connecticut. Retrieved July 1, 2015, from http://connecticut.cbslocal.com/2011/11/02/power-restoration-continues-malloy-says-not-fast-enough

Hallahan, K. (2001). The dynamics of issue activation and response: An issues process model. Journal of Public Relations Research, 13(1), 27-59.

Historic storm response. (2012). Connecticut Light & Power. Retrieved October 16, 2014, from http://www.cl-p.com/stormcenter/stormresponse.aspx

Kauffman, M. (2011, November 5). CL&P’s Butler a lightning rod for anger, frustration: No-nonsense engineer seems weary, uncomfortable in face of storm of criticism. Hartford Courant. Retrieved July 1, 2015, from http://articles.courant.com/2011-11-05/news/hc-jeff-butler-1106-20111105_1_cl-p-engineer-electric

Keating, C., & Altimari, D. (2011, November 5). Malloy orders independent review of storm response as towns’ anger grows. Hartford Courant. Retrieved July 1, 2015, from http://articles.courant.com/2011-11-05/news/hc-october-snowstorm-20111101-463_1_number-of-line-crews-emergency-crews-dannel-p-malloy

Lender, J. (2011, November 7). Malloy talks tougher about CL&P, mentions possible ‘malfeasance.’ Hartford Courant. Retrieved July 1, 2015, from http://articles.courant.com/2011-11-07/news/hc-malloy-talks-tougher-about-clp-20111107_1_dannel-p-malloy-consulting-firm-cl-p

Lender, J., & Keating, C. (2011, November 17). CL&P Chief Jeffrey Butler resigns after storm of controversy. Hartford Courant. Retrieved July 1, 2015, from http://articles.courant.com/2011-11-17/news/hc-clp-butler-1118-20111117_1_storm-response-cl-p-dannel-p-malloy

Melia, M. (2011, October 31). Snow belts East Coast: Officials expect ‘extensive and long-term’ outages. The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved July 1, 2015, from http://www.spokesman.com/stories/2011/oct/31/snow-belts-east-coast

McGee, J., & Skiff, J. (co-chairs). (2012, January 9). Report of the Two Storm Panel. Retrieved July 1, 2015, from http://www.ctsprague.org/resources/two_storm_panel_final_report.pdf

Stuart, C., & McQuaid, H. (2011, December 2). Witt Report finds CL&P was not prepared for October storm. CT News Junkie. Retrieved July 1, 2015, from http://www.ctnewsjunkie.com/archives/entry/witt_report_finds_clp_was_not_prepared

Thousands in dark week after nor’easter. (2011, November 5). NBC News. Retrieved July 1, 2015, from http://www.nbcnews.com/id/45177254/ns/weather/t/thousands-dark-week-after-noreaster/#.UsB0K2RDt4V

Turmelle, L. (2013, October 25). CL&P says new software helps restore power faster: Program can cut damage assessment time by one-third, CL&P officials say. New Haven Register. Retrieved July 1, 2015, from http://www.nhregister.com/business/20131025/clp-says-new-software-helps-restore-power-faster

Van Leuven, J. K., & Slater, M. D. (1991). How publics, public relations, and the media shape the public opinion process. Public Relations Research Annual, 3, 165-178.

Witt Associates. (2011, December 1). Connecticut October 2011 snowstorm power restoration report. Retrieved July 1, 2015, from http://www.wittobriens.com/external/content/document/2000/1883982/1/CT-Power-Restoration-Report-20111201-FINAL.pdf

SUSAN GRANTHAM, Ph.D., is an associate professor in the School of Communication at the University of Hartford. Email: grantham[at]hartford.edu.

Editorial history

Received January 10, 2014

Revised October 16, 2014

Accepted January 7, 2015

Published July 1, 2015

Handled by editor; no conflicts of interest

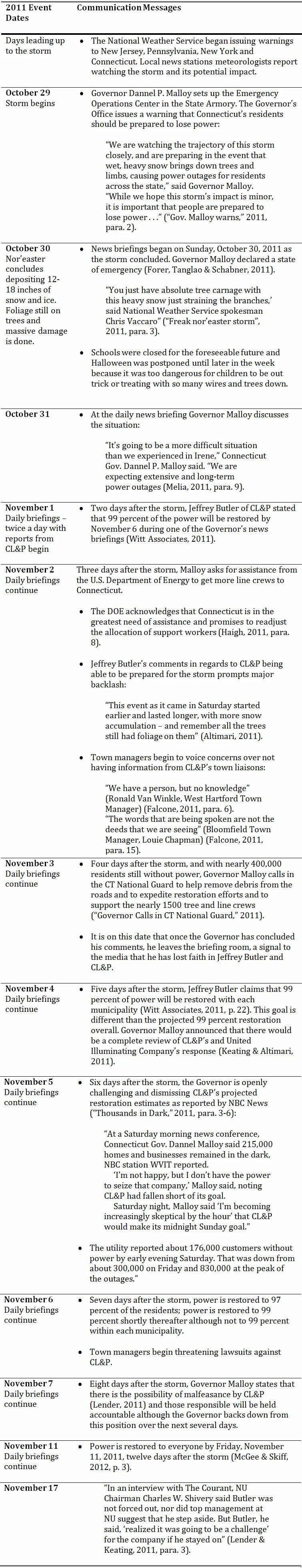

Appendix. Communication timeline and messages.