To cite this article

Sarmiento, K., Hoffman, R., Donnell, Z., & Bloodgood, B. (2016). A case study of lessons learned and the evolution of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s HEADS UP concussion in sports campaign. Case Studies in Strategic Communication, 5, article 15. Available online: http://cssc.uscannenberg.org/cases/v5/v5art15

Access the PDF version of this article

A Case Study of Lessons Learned and the Evolution of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s HEADS UP Concussion in Sports Campaign

Kelly Sarmiento

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Rosanne Hoffman

Zoe Donnell

Bonny Bloodgood

ICF International

Abstract

Traumatic brain injury (TBI), caused by a bump, blow, or jolt to the head or body, can change the way the brain normally works. Children aged 0 to 4 years and adolescents aged 15 to 19 years are at increased risk for sustaining TBI, including concussion. Since 2003, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) HEADS UP campaign has provided information to a range of audiences in an effort to help improve knowledge of how to recognize and respond to concussion or other serious TBIs. A national needs assessment and formative research identified the need for tailored resources on concussion to appeal to target audiences, and audience engagement and partner outreach served as the hallmark and guided the evolution of HEADS UP. Over the last 12 years, CDC obtained insights on strategies that helped grow HEADS UP, including understanding and listening to target audiences, investing in partnership development, and ensuring flexibility in the structure of the campaign to allow for unexpected growth and opportunities. CDC’s HEADS UP campaign provides a framework that can be used to inform other health communication campaigns focused on raising awareness and improving knowledge among multiple audiences to address important health issues.

Keywords: health communication; campaign; education; brain injuries; traumatic brain injury; pediatrics; sports; concussion

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI), caused by a bump, blow, or jolt to the head or body that can change the way the brain normally works, is a serious public health problem in the United States. TBI contributes to one-third of all injury-related deaths and costs the country an estimated $76.5 billion (Corso, Finkelstein, Miller, Fiebelkorn, & Zaloshnja, 2006; Faul, Xu, Wald, & Coronado, 2010). Children 0 to 4 years old and adolescents 15 to 19 years old are at an increased risk for sustaining a TBI (Faul et al., 2010).

Due to a wide range of short- or long-term potential health outcomes from a TBI, this injury can affect all aspects of an individual’s life, including relationships with family and friends, as well as the ability to work or be employed, do household tasks, drive, and/or participate in other activities of daily living (Thurman, Alverson, Dunn, Guerrero, & Sniezek, 1999). Some potential effects include problems with cognitive function (e.g., attention and memory); motor function (e.g., extremity weakness, impaired coordination and balance); sensation (e.g., hearing, vision, impaired perception, and touch); and emotion (e.g., depression, anxiety, aggression, impulse control, personality changes; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, 2016). While there are different types of TBI, an estimated two-thirds of TBIs are concussions or other forms of mild TBI (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control [CDC NCIPC], 2003). While a concussion is classified as a mild brain injury that is usually not life-threatening, the effects of a concussion can be serious.

More than a decade ago, awareness about TBI, including concussion, was low among the United States public. In fact, a national survey conducted in 2000 found that one in three Americans were unfamiliar with the term “brain injury” (Brain Injury Association of America, n.d.). This limited public awareness, coupled with the inability to visibly see the problems that result from a TBI, led to the labeling of TBIs as a “silent epidemic” (Faul et al., 2010).

To help address limited public awareness about TBI and its consequences, the Children’s Health Act (H.R. 4365; Children’s Health Act, 2000) charged the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (NCIPC) to, in part, implement a public information campaign to broaden public awareness of the health consequences of TBI. In response, CDC created the HEADS UP campaign, which is comprised of a series of educational initiatives designed to increase awareness about concussion and other TBIs. As of 2016, CDC’s HEADS UP campaign includes five educational initiatives:

- HEADS UP to Clinicians for health care professionals (CDC NCIPC, 2016);

- HEADS UP: Concussion in High School Sports for high school sports coaches (CDC NCIPC, 2015d);

- HEADS UP: Concussion in Youth Sports for youth sports coaches (CDC NCIPC, 2015c);

- HEADS UP to Schools: Know Your Concussion ABCs for school professionals (CDC NCIPC, 2015b); and

- HEADS UP to Parents for parents and guardians (CDC & CDC Foundation, 2016).

Background

Developed using best available knowledge and practices, the primary goal of the HEADS UP campaign is to help protect children and adolescents from concussions and their potentially devastating effects. To achieve this goal, the HEADS UP initiatives focus on translating the latest concussion science into educational products tailored specifically for key audiences, and working with partner organizations to disseminate and integrate concussion educational materials and messages into their existing systems and programs. This approach has led to the development of an assortment of educational products under the HEADS UP initiatives, ranging from videos and fact sheets to public service announcements (PSAs) with professional athletes and a mobile application (app) for parents. The initiatives have reached millions of Americans and have brought together large and diverse organizations from the public and private sectors to disseminate consistent concussion information and messaging (CDC NCIPC, 2011).

In addition to the wide reach of the initiatives, the CDC HEADS UP campaign has helped to drive the development of innovative educational efforts and to further the science to meet information and research gaps in the field.

Thus, the objectives of this case study are to:

- Review the development and evolution of CDC’s HEADS UP campaign;

- Outline three main lessons learned from 12 years of implementing the HEADS UP campaign; and

- Discuss the expansion of CDC’s HEADS UP campaign to meet the emerging needs of the target audiences.

CDC’s first HEADS UP initiative launched in 2003 with a tool kit for health care professionals working in the primary care setting. The HEADS UP: Brain Injury in Your Practice tool kit was aimed at improving awareness and addressing the concern of under-diagnosis of concussion and other mild TBIs in the United States. Educational materials in the tool kit included a patient assessment tool, palm card, care plans, and fact sheets for patients.

Research

Following the release of this tool kit, CDC conducted a comprehensive literature review and needs assessment to discover remaining gaps related to concussion knowledge, awareness, and management and to reveal other key target audiences. Important groups in need of concussion information were identified—specifically, coaches, school nurses, teachers, other school professionals, and especially parents. These audiences were identified as people who are often in a position to recognize and respond to a concussion or related symptoms. They are also potentially able to help prevent long-term problems among children and adolescents by educating others about concussions and how to respond if a concussion is suspected. CDC conducted formative research to understand the needs of these audiences and began building additional materials and components of the HEADS UP initiatives.

Strategy

CDC followed a five-pronged approach based in communication best practices to develop the subsequent HEADS UP initiatives for the identified audiences. This included:

- Conducting background and formative research to inform the content and design of the materials;

- Engaging experts in the field to review the content;

- Launching and promoting the materials through various communication channels;

- Coordinating with strategic partners throughout development and dissemination of the materials; and

- Tracking the reach of the initiative and evaluating the effectiveness of the products.

Execution

High School Coaches

Using the approach above, CDC launched its second HEADS UP initiative focused on providing information on concussion prevention, recognition, and response to high school coaches. Launched in 2005, the HEADS UP: Concussion in High School Sports initiative was CDC’s first concussion education and awareness-building effort focusing on children and adolescents participating in sports and recreational activities. Designed for high school athletic coaches, this initiative focused on educating coaches about concussions and the role coaches play in preventing concussions, and limiting subsequent health effects and preparing coaches to educate athletes and their parents about these same issues. As part of this initiative, CDC developed a suite of materials for high school coaches, including fact sheets, posters, a video, a wallet card, and clipboard sticker. Each of these items included action steps for coaches on what to do if a concussion is suspected and a list of concussion signs and symptoms.

Youth Sports Coaches

With similar objectives in mind, CDC also developed a suite of materials for youth sports coaches and administrators. Unlike high school coaches, coaches in youth sports programs are primarily volunteers—either parents or other interested people—who may have minimal or no training in coaching or safety (Wiersma & Sherman, 2005). Launched in 2007, the HEADS UP: Concussion in Youth Sports initiative included fact sheets for youth sports coaches, parents, and athletes; a poster; a magnet; a clipboard; and online training released in 2010.

School Professionals

Ongoing background research revealed a need for resources to support school professionals who are responsible for recognizing potential signs of concussions in students and providing academic accommodations to support their learning. According to a 2010 study, students with concussions and other TBIs continue to be underserved and under-identified for educational supports when they return to school (Glang, Todis, Sublette, Eagan Brown, & Vaccaro, 2010). School nurses in particular play a crucial role in concussion recognition at school, including initial assessment, as well as communication and reporting (Pennington, 2010). As such, school nurses need to be kept up to date on current concussion information to provide proper care at the time of injury and during the recovery process (Piebes, Gourley, & Valovich, 2009).

To meet this need, CDC launched the HEADS UP to Schools: Know Your Concussion ABCs initiative for school professionals (K-12) in 2010. Materials in this initiative include fact sheets for school nurses, parents, and other school professionals; a signs and symptoms checklist; a magnet; and a poster. These materials also include two fact sheets that contain strategies school professionals can use to help students return to school following a concussion, such as classroom strategies and assisting with making academic adjustments to a student’s workload or schedule.

Parents

The latest CDC HEADS UP initiative, launched in 2013, is the HEADS UP to Parents initiative, which was created in part through a grant to the CDC Foundation from the National Operating Committee on Standards for Athletic Equipment. The goal of this initiative is to provide broader access to concussion information and educational materials for parents through a website and mobile app. The initiative includes a variety of materials, including infographics, videos with concussion experts and professional athletes that parents can view and share with others, as well as fact sheets that parents can customize with their child’s or adolescent’s team or school logo and colors. Due to misinformation about the role helmets and other athletic equipment play in preventing concussion (Graham, Rivara, Ford, & Mason Spicer, 2014), the HEADS UP to Parents initiative also provides information on how to properly fit and care for helmets, ranging from football to snowboarding helmets.

Evaluation

Using innovative communication strategies grounded in concussion research; audience preferences for content, design, format; and distribution channels, CDC HEADS UP initiatives have reached millions of Americans with information on how to recognize and respond to concussion and other serious TBIs. Through this process, CDC has gained valuable insights and lessons learned regarding the framework and strategies used to maintain and grow these initiatives, including the importance of:

- Understanding and listening to the target audiences;

- Investing in partnership development and nurturing these relationships; and

- Establishing goals and a plan for the campaign, but allowing for flexibility and growth.

Understanding and Listening to the Target Audiences

With children and adolescents at the focus of every HEADS UP initiative, CDC conducted ongoing research of the target audiences to keep the HEADS UP campaign current and to identify opportunities for enhancement. Before developing each HEADS UP initiative, CDC conducted an environmental scan to assess the current research and formative testing to assess the content, format, and design of the materials. For example, CDC conducted in-depth interviews with a range of school professionals to test the HEADS UP to Schools materials. The findings indicated that the content was useful for school professionals, but that they preferred a more colorful, engaging design with clearly delineated sections. CDC used this insight to create a more effective design and conducted a second round of formative testing to ensure that the new design met the needs and preferences of school professionals. This second round of testing was also an opportunity to learn about preferred dissemination channels and how to best get HEADS UP materials to school professionals. As with each of the HEADS UP initiatives, formative testing made certain that the resource content, design, and outreach strategies were grounded in audiences’ preferences.

CDC also routinely engaged content experts and partner organizations to provide feedback on all content and materials to ensure accuracy and credibility. Expert reviewers brought a deep understanding of the target audiences, insights about the contexts in which they work and live, and an understanding of the barriers audiences face in addressing concussions.

Equally as important, CDC worked to stay connected with and listen to the target audiences by obtaining and communicating personal stories about concussion and the potential impact of this injury. As an example, the CDC HEADS UP Facebook community of more than 25,000 fans share resources and personal stories of concussion. This online conversation cultivates hope and support among caregivers and people living with concussions or other serious TBIs. In 2012, in recognition of Brain Injury Awareness Month, CDC launched the HEADS UP Film Festival that invited the public to share videos and personal stories and help create a national conversation on brain injury. Users tagged their videos on YouTube with “HEADS UP Film Festival,” and CDC selected several to post on the HEADS UP YouTube channel. Both of these activities provided an important platform for CDC to hear from the public and adapt the campaign’s messages to meet the needs of the audience. For instance, based on feedback from Facebook fans and stories posted through the HEADS UP Film Festival, CDC expanded social media messages on HEADS UP to include motor vehicle safety and support services for people and families living with TBI.

CDC also interviews and captures personal stories to present the real-life experiences of parents and young athletes with concussion. These stories are presented as fact sheets and/or videos that weave together concussion research with personal stories. The first of these personal stories is the “Tracy’s Story” video (CDC, 2010). In this video, Tracy shares her experiences with concussions and how important it is for athletes to stay out of play when they have a concussion (see Figure 1). Creating relationships with TBI survivors and incorporating real stories into HEADS UP materials has not only helped CDC communicate information, but also build connections in local communities. To date, more than 65,000 viewers have watched this video on CDC’s YouTube channel. In Tracy’s home state, the video is also adapted for use in school presentations to students on concussions and aired on a loop in the state capitol building.

Figure 1. “Tracy’s Story” video featuring a personal story of concussion. Click the screen shot to view the video on YouTube.Investing in Partnership Development and Nurturing these Relationships

Many organizations contributed to the success of the HEADS UP campaign by offering important expertise and guidance, enhancing credibility among key audiences, supporting research and evaluation efforts, and providing cost-effective distribution channels. CDC has partnered with more than 85 organizations on HEADS UP initiatives to help expand their reach. Some examples of the organizations that participate in HEADS UP efforts, and the ways in which they offer their support and engagement, include:

- Health and medical organizations: Use HEADS UP information to enhance health education and ensure concussion messaging used by health care professionals to educate patients is based on the latest science.

- School organizations: Disseminate HEADS UP information to a large network of school professionals. Information provided to staff updates them on the latest concussion science to help students safely return to school after a concussion.

- Sports and youth-serving organizations: Use HEADS UP information to educate a large number of parents, coaches, and young athletes through their communication channels, as well as their associated state and local affiliates. Some of these organizations also use HEADS UP materials to assist with implementation of policies and/or state legislation on concussions in sports.

HEADS UP grew significantly through the support of partners who already had access to and credibility with the target audience. CDC invited its partners to co-brand the HEADS UP materials to include their organizations’ logos and colors. To date, CDC has co-branded more than 15 products with partner organizations. Examples include a poster and fact sheet for young athletes developed in partnership with the National Football League (NFL), NFL Players’ Association, and 16 governing bodies for sports (such as US Lacrosse and USA Hockey). These materials help present a cohesive message to young athletes across multiple sports on the importance of reporting injury and taking time to recover after a concussion. These fact sheets and posters now hang in school and sports locker rooms across the country. Additionally, some schools and organizations provide a copy of the fact sheet or other HEADS UP materials to parents as part of their child’s or adolescent’s sport registration packet.

Along with a cohesive and consistent message used across multiple sports, CDC also partnered with individual sports and youth organizations to provide tailored messages to appeal to specific audiences. For example, CDC worked with YMCA of the USA and Safe Kids USA to co-brand HEADS UP fact sheets for their local chapters, as well as with groups such as USA Cheer, to create sports-specific information. These co-branded items are integrated into the existing programs and health education efforts of these organizations. For example:

- CDC HEADS UP and Safe Kids USA materials became an integral part of the Safe Kids Sports Safety Program that reached thousands of coaches, parents, and young athletes through more than 60 concussion training sessions led by local certified athletic trainers.

- CDC HEADS UP, USA Cheer, and the American Association of Cheerleading Coaches and Administrators distribute co-branded materials every summer to coaches in cheerleading camps, reaching approximately 450,000 middle and high school cheerleaders each year.

Establishing Goals and a Plan for the Campaign, While Allowing for Flexibility and Growth

Over the last 12 years, the CDC’s HEADS UP campaign has maintained consistent goals and objectives while it expanded to new audiences and while concussion research quickly evolved. To help keep HEADS UP relevant, fresh, and accessible, the initiatives were built around a flexible approach that combined formative research findings with insights from partner organizations. Each initiative had shared goals and consistent messaging that was tailored to meet each key audience’s specific information needs. This approach allowed for necessary flexibility for the materials to be integrated into existing communication channels and programs at various types of organizations. For example, HEADS UP resources for coaches provide clear and concise information about recognizing the signs and symptoms of concussions and how to respond. This type of content can easily be repurposed by other coach-serving organizations and incorporated into their educational programs to expand the reach of HEADS UP messages.

Many local organizations have also leveraged CDC HEADS UP content and materials to launch local city- and state-specific HEADS UP efforts, including HEADS UP Pittsburgh, HEADS UP Michigan, HEADS UP Washington, HEADS UP Nebraska, and HEADS UP Northern California. These city and state HEADS UP efforts have led to innovative local initiatives that resulted in PSAs and social media campaigns, as well as integration of HEADS UP information into medical care settings.

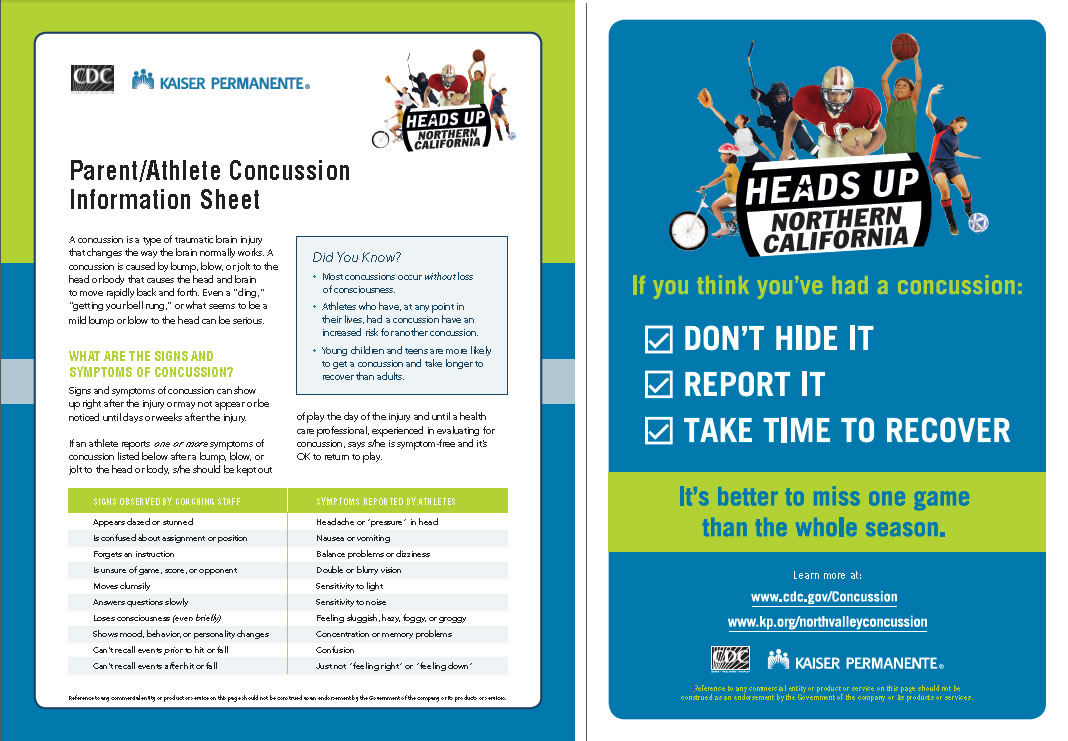

These activities greatly enhanced the reach of the HEADS UP materials and helped grow the initiatives in unique ways that could not otherwise have been achieved. For example, HEADS UP Washington, which was the first local HEADS UP effort, resulted in the development of a PSA created in partnership with the Seattle Seahawks and aired during their games (see Figure 2). Additionally, the HEADS UP Northern California effort resulted in the integration of HEADS UP fact sheets in all local Kaiser Permanente pediatric and emergency care clinics. The materials were also distributed through the local school systems, reaching thousands of coaches, parents, and students (see Figure 3).

Figure 2. Seattle Seahawks PSA on the HEADS UP program. Click the screen shot to view the video on YouTube. Figure 3. HEADS UP Northern California concussion resources.The flexibility and adaptable nature of the CDC HEADS UP materials also allowed for opportunities to help address emerging needs in the field. As an example, when HEADS UP started, it predominately developed print resources and tool kits for the target audiences. However, with the passage of sports concussion laws in all 50 states and the District of Columbia over a four-year period, a significant need arose to provide streamlined information that could be used on a large scale. In response, CDC created online trainings based on content in the HEADS UP print materials. These trainings are used by states to implement components in many of the laws that require education for coaches and/or health care providers on concussion in a cost-effective manner using easy-to-access formats (Harvey, 2013). More than 2 million people have completed one of these online trainings created through CDC HEADS UP over the last few years.

Analysis and Discussion

CDC HEADS UP has grown from a small-scale effort targeting health care professionals, into a series of initiatives for diverse audiences with broad partnerships that help the initiatives reach out to people across the country (see Figure 4). While CDC did not start out with the intention of creating these wide-reaching initiatives, HEADS UP continued to grow in unanticipated directions by adapting to new technologies and continuing to fill information gaps identified through research and evaluation. The CDC HEADS UP campaign has made a concerted effort to listen to its key audiences, experts in the field, and partners who work directly with intended audiences. These groups guided each step of the process, expressing their needs, identifying barriers, exploring solutions, and providing feedback on new resources to meet their needs, as well as those that missed the mark. Audience engagement and partnership outreach has served as the foundation of HEADS UP and led to the evolution of the initiatives.

Figure 4. Sample HEADS UP materials by initiative, including a) HEADS UP Youth Sports, b) HEADS UP to Schools, c) HEADS UP High School Sports, d) HEADS UP to Healthcare Providers, and e) HEADS UP to Parents.Since HEADS UP launched 12 years ago, growing research, media coverage, and educational initiatives on TBI, especially concussion, have helped raise awareness about this public health problem and given a voice to a once “silent epidemic.” This increasing awareness is specifically evident among the sports community. In fact, research suggests that the majority of youth athletes and parents have heard about concussions (Bloodgood et al., 2013), and an online survey of parents and youth athletes found that more than four out of five youth athletes and parents reported that they had heard about concussions (Bloodgood et al., 2013).

Coupled with this growing awareness is the growth of policies and laws around concussion. As of 2013, nearly every state had legislation on concussions in sports among young athletes (“Concussion Laws by State,” 2014). Similarly, many schools and sport organizations have created policies or action plans on concussion in youth and high school sports.

However, more needs to be done, as many young athletes do not report their concussion (Chrisman, Quitiquit, & Rivara, 2013), are not removed from play and continue playing with concussion symptoms (O’Kane et al., 2014; Register-Mihalik, Guskiewicz, et al., 2013; Rivara et al., 2014; Valovich McLeod, Schwartz, & Bay, 2007), and/or return to play too soon (Hwang et al., 2014; Yard & Comstock, 2009).

Research suggests that reporting of concussion among young athletes may be more connected to the overall culture and environment in which athletes play versus their knowledge of this injury (Register-Mihalik, Linnan, et al., 2013). Some reasons why concussions are still often underreported among youth athletes may include a fear of being removed from the game and a lack of perceived seriousness of the injury (McCrea, Hammeke, Olsen, Leo, & Guskiewicz, 2004; Williamson & Goodman, 2006). These findings indicate that the needs of the target audiences have evolved. No longer is there a need for general awareness and knowledge of concussion, but rather a need for guidance on changing behaviors and social norms, especially among children and adolescents. In 2015, CDC released Concussion at Play: Opportunities to Reshape the Culture Around Concussion in Sports, a report that provides a snapshot of current research on concussion knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors (see Figure 5). The report offers strategies based on existing research to keep athletes safe and help create a safe sport culture (CDC NCIPC, 2015a).

Figure 5. Concussion at Play: Opportunities to Reshape the Culture Around Concussion, a report of current research on concussion from the CDC.Over the next decade, CDC HEADS UP will continue to adapt and enhance its products, messaging, and dissemination strategies, to reach out to children and adolescents on issues related to social norms and the culture of concussions in sports. This evolution will necessitate evaluating current social norms among children and adolescents and developing innovative strategies and resources to help meet this information gap. An example of one such resource is a new HEADS UP video titled, “Thank You, Coach,” which recognizes sports coaches for their hard work to protect young athletes from concussion (see Figure 6). As with the other HEADS UP initiatives, this next phase will require the continued engagement of experts in the field and partner organizations that can provide insights and direct communication with this audience, as well as a strong grounding in research and a focus on developing creative educational materials.

Figure 6. HEADS UP “Thank You, Coach” video. Click the screen shot to view the video on YouTube.Over the past 12 years, CDC’s HEADS UP initiatives have evolved into an ongoing effort to provide needed resources to health care professionals, coaches, school professionals, and parents. Using an approach that is grounded in the latest science on concussion research, formative research with key audiences, partnership development, and the use of a flexible framework, CDC’s HEADS UP initiatives have achieved numerous accomplishments. In particular, this approach has advanced public awareness of concussion recognition, response, and prevention throughout the United States.

Discussion Questions

- How can CDC strategically engage new stakeholders (partner organizations) to help in disseminating CDC HEADS UP materials and educating people in the future?

- What strategies would you recommend to help CDC’s HEADS UP spread more widely at the local level? What role could national partners play in this expansion?

- How could the CDC build out a more comprehensive social media plan for its HEADS UP program? What elements should a social media plan include to allow for broad consumption? Consider the evolving nature of social media and the needs and preferences of HEADS UP audiences.

- Identify practical ways the CDC can continue to use HEADS UP resources to change the culture around concussions among key audiences, including athletes, coaches, parents, health care professionals and school professionals.

References

Bloodgood, B., Inokuchi, D., Shawver, W., Olson, K., Hoffman, R., Cohen, E., Sarmiento, K., Muthuswamy, K. (2013). Exploration of awareness, knowledge, and perceptions of traumatic brain injury among American youth athletes and their parents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(1), 34-39.

Brain Injury Association of America. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.biausa.org/Default.aspx?PageID=4443913&A=SearchResult&SearchID=9497972&ObjectID=4443913&ObjectType=1

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010). Survivor stories. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/headsup/resources/stories.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. (2003, September). Report to Congress on mild traumatic brain injury in the United States: Steps to prevent a serious public health problem. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/pdf/mtbireport-a.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. (2011). Addressing concussion among kids and teens: On and off the playing field. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/headsup/pdfs/youthsports/activity_report2011-a.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. (2015a). Concussion at play: Opportunities to reshape the culture around concussion. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/headsup/pdfs/resources/concussion_at_play_playbook-a.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. (2015b, February 16). HEADS UP to schools: Know your concussion ABCs. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/headsup/schools/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. (2015c, August 19). HEADS UP: Concussion in youth sports. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/headsup/youthsports/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. (2015d, December 22). HEADS UP: Concussion in high school sports. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/headsup/highschoolsports/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. (2016). HEADS UP: Brain injury in your practice. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/headsup/providers/tools.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention & CDC Foundation. (2016). HEADS UP to parents. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/headsup/parents/index.html

Children’s Health Act of 2000, Pub.L. 106-310, 114 Stat. 1101 (2000).

Chrisman, S. P., Quitiquit, C., & Rivara, F. P. (2013). Qualitative study of barriers to concussive symptom reporting in high school athletics. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 52(3), 330-335.

Concussion laws by state. (2014, April 17). Education Week. Retrieved from http://www.edweek.org/ew/section/infographics/37concussion_map.html

Corso, P., Finkelstein, E., Miller, T., Fiebelkorn, I., & Zaloshnja, E. (2006). The incidence and economic burden of injuries in the United States. Injury Prevention, 12(4), 212-218.

Faul, M., Xu, L., Wald, M. M., & Coronado, V. G. (2010). Traumatic brain injury in the United States: Emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths 2002-2006. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/pdf/blue_book.pdf

Glang, A., Todis, B., Sublette, P., Eagan Brown, B., & Vaccaro, M. (2010). Professional development in TBI for educators: The importance of context. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 25(6), 426-432.

Graham, R., Rivara, F. P., Ford, M. A., & Mason Spicer, C. (Eds.). (2014). Sports-related concussions in youth: Improving the science, changing the culture. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Harvey, H. H. (2013). Reducing traumatic brain injuries in youth sports: Youth sports traumatic brain injury state laws, January 2009-December 2012. American Journal of Public Health, 103(7), 1249-1254.

Hwang, V., Trickey, A. W., Lormel, C., Bradford, A. N., Griffen, M. M., Lawrence, C. P., Sturek, C., Stacey, E., & Howell, J. M. (2014). Are pediatric concussion patients compliant with discharge instructions? The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 77(1), 117-122.

McCrea, M., Hammeke, T., Olsen, G., Leo, P., & Guskiewicz, K. (2004). Unreported concussion in high school football players: Implications for prevention. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine: Official Journal of the Canadian Academy of Sport Medicine, 14(1), 13-17.

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (2016, September 8). Traumatic brain injury: Hope through research. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health. Retrieved from http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/tbi/detail_tbi.htm

O’Kane, J. W., Spieker, A., Levy, M. R., Neradilek, M., Polissar, N. L., & Schiff, M. A. (2014). Concussion among female middle-school soccer players. JAMA Pediatrics, 168(3), 258-264.

Pennington, N. (2010). Head injuries in children. The Journal of School Nursing: The Official Publication of the National Association of School Nurses, 26(1), 26-32.

Piebes, S. K., Gourley, M., & Valovich, T. C. (2009). Caring for student-athletes following a concussion. The Journal of School Nursing: The Official Publication of the National Association of School Nurses, 25(4), 270-281.

Register-Mihalik, J. K., Guskiewicz, K. M., McLeod, T. C., Linnan, L. A., Mueller, F. O., & Marshall, S. W. (2013). Knowledge, attitude, and concussion-reporting behaviors among high school athletes: A preliminary study. Journal of Athletic Training, 48(5), 645-653.

Register-Mihalik, J. K., Linnan, L. A., Marshall, S. W., Valovich McLeod, T. C., Mueller, F. O., & Guskiewicz, K. M. (2013). Using theory to understand high school aged athletes’ intentions to report sport-related concussion: Implications for concussion education initiatives. Brain Injury, 27(7-8), 878-886.

Rivara, F. P., Schiff, M. A., Chrisman, S. P., Chung, S. K., Ellenbogen, R. G., & Herring, S. A. (2014). The effect of coach education on reporting of concussions among high school athletes after passage of a concussion law. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 42(5), 1197-1203.

Thurman, D. J., Alverson, C., Dunn, K. A., Guerrero, J., & Sniezek, J. E. (1999). Traumatic brain injury in the United States: A public health perspective. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 14(6), 602-615.

Valovich McLeod, T. C., Schwartz, C., & Bay, R. C. (2007). Sport-related concussion misunderstandings among youth coaches. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine: Official Journal of the Canadian Academy of Sport Medicine, 17(2), 140-142.

Wiersma, L. D., & Sherman, C. P. (2005). Volunteer youth sports coaches’ perspectives of coaching education/certification and parental codes of conduct. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 76(3), 324-338.

Williamson, I. J., & Goodman, D. (2006). Converging evidence for the under-reporting of concussions in youth ice hockey. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 40(2), 128-132.

Yard, E. E., & Comstock, R. D. (2009). Compliance with return to play guidelines following concussion in US high school athletes, 2005-2008. Brain Injury, 23(11), 888-898.

KELLY SARMIENTO, M.P.H., is a health communications specialist in the Division of Unintentional Head Injury Prevention at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. She leads the HEADS UP program.

ROSANNE HOFFMAN, M.P.H., is a senior manager at ICF International and manages the HEADS UP project to support CDC’s work. Email: rosanne.hoffman[at]icfi.com.

ZOE DONNELL is an associate at ICF International and works on HEADS UP and other health communication efforts.

BONNY BLOODGOOD, M.A., is a senior associate at ICF International and has led the formative research for the HEADS UP campaign.

Acknowledgment

The HEADS UP campaign is a program of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Declarations

A version of the contents of this paper was previously presented by the author in 2013 at the National Conference on Health Communication Marketing and Media, which can be found here: http://www.cdc.gov/NCHCMM/registration.html. In addition, the company ICF International has a contract with CDC to support its work on HEADS UP.

The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and shall not be used for advertising or product endorsement purposes. Reference herein to any specific commercial products, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Editorial history

Received July 20, 2016

Revised December 1, 2016

Accepted December 1, 2016

Published December 6, 2016

Handled by editor; no conflicts of interest