To cite this article

Duhon, S., Ellison, K., & Ragas, M. W. (2016). A whale of a problem: A strategic communication analysis of SeaWorld Entertainment’s multi-year Blackfish crisis. Case Studies in Strategic Communication, 5, article 2. Available online: http://cssc.uscannenberg.org/cases/v5/v5art2

Access the PDF version of this article

A Whale of a Problem: A Strategic Communication Analysis of SeaWorld Entertainment’s Multi-Year Blackfish Crisis

Stefani Duhon

Kelli Ellison

Matthew W. Ragas

DePaul University

Abstract

The release of the controversial documentary Blackfish and its airings on CNN in the fall of 2013 sparked a widespread backlash against SeaWorld that thrust the theme park operator into a multi-year crisis. Blackfish places emphasis on the tragic death of SeaWorld trainer Dawn Brancheau by Tilikum, a killer whale. This case study covers the evolution and shift in SeaWorld’s communication strategy and tactics, from a defensive, advocacy posture immediately before and for several months after the release of Blackfish, to a blend of advocacy and accommodation backed by tangible business actions after the fallout persisted and intensified. This case is unique in that it focuses on a well-known brand in a multi-year crisis in which a key aspect of its business model—keeping and raising killer whales in captivity—is being called into question by stakeholders, including media-savvy animal rights activists, and some customers, business partners and government regulators. Strategic communication implications and takeaways from this case are provided.

Keywords: SeaWorld; Blackfish; CNN; crisis communication; corporate communication; corporate social responsibility; social media; activists and activism

Introduction

SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc. has spent the past few years dealing with a whale of a problem. For decades, the theme park operator’s star attraction at its SeaWorld amusement parks has been its choreographed, stadium-style Shamu water shows featuring orca whales, better known as killer whales. The company is so connected with the whales that its old logo featured the distinctive image of a big black and white whale jumping in the air. As recently as the initial public offering (IPO) of SeaWorld Entertainment shares in April 2013, SeaWorld senior executives rang the opening bell at the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) with a large model of a jumping killer whale behind them (Morton, 2013). An enormous banner with an image of the distinctive black and white marine mammal even hung outside the exterior of the NYSE building on Wall Street to commemorate the occasion (“SeaWorld Entertainment IPO,” 2013).

Animal welfare activist groups like People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) have long criticized the practices of zoos, theme parks and circus operators, arguing that animal captivity adversely affects the well-being of animals (Davis, 2015; “Ringling Bros. Says,” 2015). The tragic death in February 2010 of SeaWorld trainer Dawn Brancheau by Tilikum, a SeaWorld orca, generated new discussions about animal welfare in captivity and SeaWorld safety practices. The 2013 release of the anti-SeaWorld documentary Blackfish brought the death of Brancheau and the Tilikum story to a much broader audience (Eberi, 2013). The broadcasts of Blackfish by CNN in fall 2013 attracted large viewing audiences, serving as the triggering events for a tsunami of backlash against SeaWorld by the news media, activist groups and the company’s various stakeholders, including consumers, investors, business partners and government regulators.

Several years after Blackfish first premiered, SeaWorld as an organization is still trying to pick up the pieces and rebuild its battered reputation with the public and its stakeholders. Amid the swirl of controversy hanging over it, attendance at SeaWorld’s parks have declined, the company’s financial performance has weakened, some sponsors and entertainers have cancelled their partnerships, and the SeaWorld C-suite has been shaken up (“SeaWorld Credit Rating,” 2014). Throughout this tumultuous period, SeaWorld has vehemently defended its treatment of its killer whales, the safety of its trainers, and its commitment to killer whale research and conservation (SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc., 2015a, 2015b, 2015c, 2015d, 2015e, 2015f, 2015g).

The following case first provides background into SeaWorld’s history and the lead up to and release of Blackfish. The case then concentrates on the evolution and shift in SeaWorld’s communication strategy and tactics, from a defensive, advocacy posture immediately before and directly after the release of Blackfish, to a blend of advocacy and accommodation backed by tangible business actions after the fallout persisted and intensified. This case is unique in that it focuses on a well-known brand in a multi-year crisis in which a key aspect of its business model—the very concept of marine-mammal theme parks in which killer whales are kept in captivity—is being called into question by stakeholders, including media-savvy activist groups.

What role can and should strategic communication play in such a prolonged crisis? How should a corporation respond when some feel the very nature of its business is harmful and unjust? What actions has SeaWorld taken to try and alleviate the concerns of its critics? What future actions should it take? Will any of SeaWorld’s efforts be deemed acceptable by its critics short of ending all of its killer whale shows and no longer keeping these animals in captivity? The conclusion section of the case addresses these questions, while providing a range of implications and takeaways for discussion and reflection among current and aspiring strategic communication professionals.

Background

History of SeaWorld

SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc. (NYSE: SEAS) is comprised of Busch Gardens, SeaWorld, Aquatica, Discovery Cove, Adventure Island, Water Country USA and the Sesame Street-themed theme park Sesame Place. The theme park and entertainment company began in March 1959 with the opening of Busch Gardens in Tampa, Florida. A few years later, in 1964, the first SeaWorld opened in San Diego, California. SeaWorld was founded by George Millay, Milt Shedd, Ken Norris and David DeMott and was originally intended to be an underwater restaurant. The idea quickly expanded and eventually became a marine zoological park along the shore of Mission Bay, California (SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc., 2015e).

SeaWorld’s first year in business drew more than 400,000 visitors—a surprising number when considering that the company began with only 45 employees, two salt-water aquariums and a few sea lions and dolphins. Starting with a $1.5 million investment, SeaWorld has expanded to three SeaWorld parks in the United States. These parks can be found in San Diego, California, and San Antonio, Texas, as well as at its headquarters in Orlando, Florida. SeaWorld currently operates and maintains eleven theme parks throughout the United States with a collection of approximately 89,000 marine and terrestrial animals (SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc., 2015e).

In 2009, private equity firm The Blackstone Group (NYSE: BX) bought the company from Anheuser-Busch InBev (NYSE: BUD) for $2.7 billion. In December of 2011, after being a private company for 55 years, Blackstone-controlled SeaWorld filed for an IPO (Kirchfeld, 2012). The process of going public and meeting ongoing public company reporting requirements meant that SeaWorld would be more in the spotlight not just with investors, but with other stakeholder groups, including activists. In April 2013, SeaWorld raised $702 million in capital by offering 26 million shares at $27 each in its IPO on the NYSE (Spears, 2013).

According to SeaWorld’s fiscal year 2014 10-K filing (SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc., 2015a) with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), all parks combined generated 22.4 million visitors with 3.6 million of these visitors being international. There was also an average of 25,800 employees with 4,500 full-time, 7,300 part-time and 14,000 seasonal workers. In 2014, these guests helped SeaWorld generate $1.38 billion in total revenue and net income of $49.9 million (SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc., 2015a). According to Yahoo! Finance, as of early 2016, based on a stock price of approximately $19.00 per share and with 89.6 million shares outstanding, SeaWorld has a market capitalization or market value of around $1.7 billion (“SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc. (SEAS) – Key Statistics,” 2015).

Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability

SeaWorld’s 10-K filing also outlines the company’s commitment to corporate social responsibility (CSR) and sustainable business practices in its parks, in its communities and with its stakeholders. For example, SeaWorld’s community relations and philanthropic efforts include partnering with charities such as hospitals and organizations that serve children with disabilities. The company also supports animal shelter and rescue groups and provides financial support, resources and hands-on volunteer services to each group (SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc., 2015a).

By offering educational outreach visits to inner city schools as well as allowing “special wish” children to visit any of its theme parks, SeaWorld believes that it can “inspire and educate children and guests of all ages through the power of entertainment” (SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc., 2015a, p. 16). The 2014 10-K also mentions SeaWorld’s free admission program to active U.S. military personnel and their families.

SeaWorld says that it is committed to the safety and welfare of animals in the wild. For more than fifty years, SeaWorld has participated in rescuing animals in crisis in the wild. These animals are taken to SeaWorld facilities where they are rehabbed and released back into the wild. If the animals are unable to return to the wild, SeaWorld provides them with lifelong care. SeaWorld estimates that 24,000 animals have benefitted from this program (SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc., 2015a). In the words of SeaWorld: “Through our theme parks’ up-close animal encounters, educational exhibits and innovative entertainment, we strive to inspire each guest who visits one of our parks to care for and conserve the natural world” (SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc., 2015a, p. 15).

SeaWorld states in its 10-K that it maintains “strict safety procedures for the protection of our employees and guests” (SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc., 2015a, p. 24). SeaWorld discloses it has revised its safety protocols, specifically the protocols used by SeaWorld trainers in show performances, following the death of a trainer “while engaged in an interaction with a killer whale” (SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc., 2015a, p. 24).

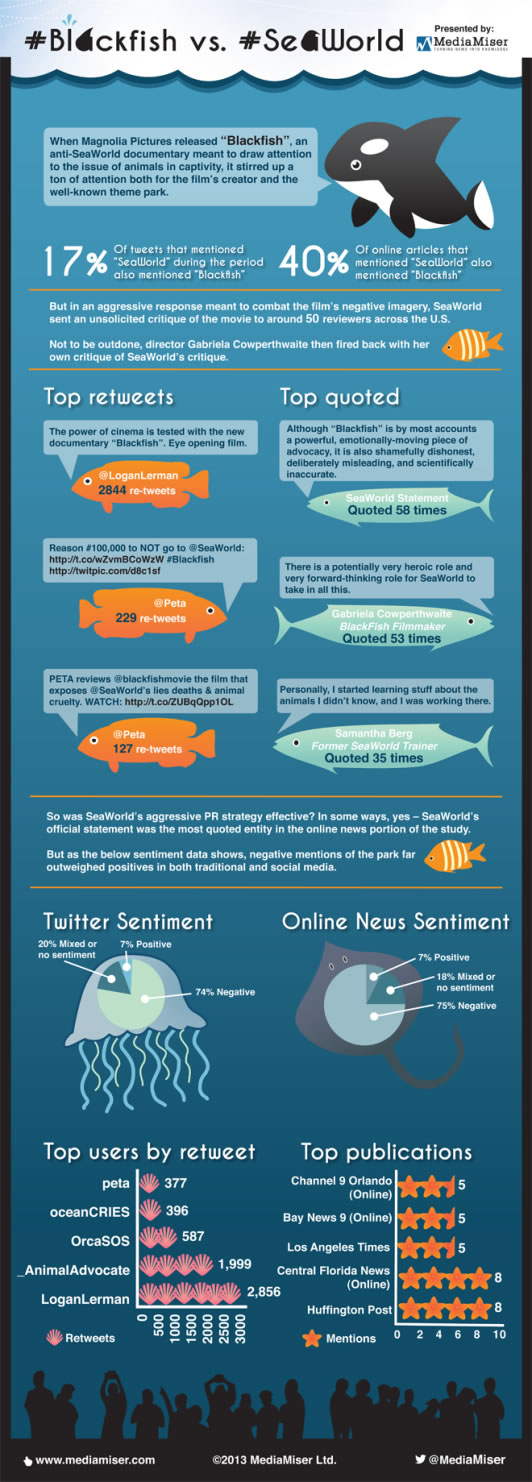

Dawn Brancheau and Tilikum Tragedy

On February 24, 2010, 12,000-pound orca Tilikum attacked female trainer, Dawn Brancheau, at SeaWorld in Orlando, which resulted in her tragic death. According to a statement issued by the U.S. Labor Department’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA): “Video footage shows the killer whale repeatedly striking and thrashing the trainer, and pulling her under water even as she attempted to escape. The autopsy report describes the cause of death as drowning and traumatic injuries” (“US Labor Department’s OSHA,” 2010, para. 3). This occurrence generated worldwide media coverage, prompting SeaWorld to cancel its killer whale shows in both Orlando and San Diego. SeaWorld progressively updated its blog regarding the incident and sent a tweet from the SeaWorld Shamu Twitter account, stating that they would not be active during this difficult time (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Tweet from @Shamu account following death of Dawn Brancheau (Source: @Shamu/SeaWorld).Following Dawn Brancheau’s death, OSHA conducted a six-month investigation. In 2012, two years after her death, SeaWorld was issued multiple citations for a total penalty of $75,000. According to the complaint, one citation was for failing to equip two of the stairways with proper stair railings on each side (Secretary of Labor v. SeaWorld, 2011). Another citation alleged violation of a general duty clause of OSHA by “exposing animal trainers to struck-by and drowning hazards when working with killer whales during performances” (Secretary of Labor v. SeaWorld, 2011, para. 4). A third citation was for failing to close outdoor electrical receptacles. SeaWorld vigorously denied OSHA’s claims (Secretary of Labor v. SeaWorld, 2011, para. 4).

SeaWorld continues to come under fire from government regulators regarding workplace safety. In May 2015, the California Division of Occupational Safety and Health issued $26,000 worth of citations to SeaWorld’s San Diego park (“SeaWorld Cited,” 2015). According to these citations, SeaWorld does not sufficiently protect its killer whale trainers at this park. SeaWorld denies the charges and says they reflect a misunderstanding of orca care and trainer safety (“SeaWorld Cited,” 2015).

PETA and Animal Welfare Activist Groups

SeaWorld has long been a target of animal welfare activist groups, such as PETA. These groups believe that animal captivity adversely affects the well-being and health of animals (Davis, 2015).

PETA filed a lawsuit against SeaWorld in October 2011 for violating orca whales’ constitutional rights. This was the first case of its kind and sought to apply the Thirteenth Amendment to “nonhuman animals” (PETA, 2011, para. 1). The lawsuit claimed that five wild-captured orcas were taken from their natural habitats and forced to perform at SeaWorld as “slaves” (PETA, 2011, para. 1). Tilikum was one of the five orcas included in the lawsuit. PETA President Ingrid E. Newkirk claimed,

all five of these orcas were violently seized from the ocean and taken from their families as babies. They are denied freedom and everything else that is natural and important to them while kept in small concrete tanks and reduced to performing stupid tricks. (PETA, 2011, para. 4)

In February 2012, the case was dismissed by U.S. District Judge Jeffrey Miller, who ruled that the Thirteenth Amendment applies only to persons and not non-persons, such as orcas (Zelman, 2012). In response to the ruling, SeaWorld provided a statement to the media in which it said the speed of the judge’s decision speaks to “the absurdity of PETA’s baseless lawsuit” (Zelman, 2012, para. 5).

Timeline of Events Before and After Blackfish

While PETA had struck out in the courts in its battle against SeaWorld, just a year later, in 2013, it was poised to gain substantial support for its cause in the “court of public opinion” thanks to the release of the Blackfish documentary. The following timeline outlines the key events surrounding SeaWorld leading up to the release of Blackfish and the major events that transpired in the two years after the release of the film:

| Timeline of Events Surrounding the Release of Blackfish |

|---|

|

The Blackfish Documentary

The Sundance Film Festival is considered the premier annual festival for independent filmmakers. Nearly 46,000 viewers attended the January 2013 edition of Sundance, where 193 films were screened, including Blackfish, which was one of the films to debut at that year’s festival (Sundance Institute, 2014). A documentary directed and produced by Gabriela Cowperthwaite, Blackfish focuses on the capture and training of killer whales, but emphasizes the story of Tilikum (or “Tilly”), an orca held in captivity at SeaWorld who has exhibited violent behavior. Prior to being housed at SeaWorld, Tilikum was one of three whales located at Sealand of the Pacific, a marine park in British Columbia (Cowperthwaite & Oteyza, 2013).

The first incident involving Tilikum was at Sealand on February 20, 1991, where a trainer tripped and was then pulled into the water by a whale. According to the documentary, reports and eyewitnesses could not identify which whale pulled the trainer under, as there were three in the exhibit at the time. Two witnesses who were in attendance at the park that day charge in the documentary that it was Tilikum. The second incident occurred on July 7, 1999, when a visitor to SeaWorld hid after a show and the park had closed. This individual entered into the tank with Tilikum and was found dead in the orca pool the next morning. The third and most recent incident was the highly publicized death of SeaWorld trainer Dawn Brancheau. On February 24, 2010, Tilikum was participating in a show with Brancheau, an experienced trainer, when the orca violently thrashed her around and drowned her (Cowperthwaite & Oteyza, 2013).

The Blackfish documentary highlights these incidents and focuses on the psychology and research behind the captivity of orca whales for entertainment (Cowperthwaite & Oteyza, 2013). The documentary makes a strong case against keeping highly social animals such as orcas in captivity, arguing that placing orcas in confined environments and altering their family structures is harmful to the orcas and can lead to aggressive and even deadly behaviors (Cowperthwaite & Oteyza, 2013).

Following the initial buzz over Blackfish at Sundance, global news organization CNN, a unit of Time Warner, secured the rights to air the documentary on its CNN cable news channel. Blackfish premiered on October 24, 2013, with an encore broadcast on November 2, 2013 (Hare, 2013). The airings of Blackfish on CNN reached an audience many times the size the documentary had received at Sundance and in theaters. CNN estimates an audience of nearly 21 million for Blackfish (Kuo & Savidge, 2014).

In addition to the widespread audience that CNN was able to capture, the changing technology landscape also makes it difficult for the momentum of Blackfish to fully diminish over time. The rise of online streaming platforms such as Netflix has allowed for more members of the public to easily watch the documentary far after its initial airings on CNN and at Sundance. Because of the rise of on-demand streaming services, the visibility of a controversial documentary no longer fully goes away. For example, as of December 2015, Blackfish was still one of the ten highest rated science and nature documentaries among U.S. Netflix users of the popular streaming service.

Strategy

SeaWorld’s initial communication strategy before and directly after the release of Blackfish appears to have been one of pure advocacy with a defensive posture (DiPietro, 2015; Greenfeld, 2014). Only after the fallout from Blackfish persisted, including business partners and entertainers canceling agreements and attendance declining, did SeaWorld publicly shift to more of a blend of both advocacy and accommodation. Further, SeaWorld’s strategy evolved into communication backed by tangible business actions (i.e., “word and deeds”) that showed efforts to at least partially listen to and address stakeholder concerns, rather than an initial approach that largely seemed to focus on advocacy messages (but with limited new actions).

Execution and Tactics

Initial SeaWorld Response to Blackfish

Prior to the debut of Blackfish in theaters in New York and Los Angeles in July 2013, SeaWorld created and posted a highly detailed critique of the documentary on its website. This analysis was sent to film critics prior to the debut. In this detailed rebuttal, SeaWorld provides details on the former trainers interviewed, the clips shown, and how the information presented is misleading (Ebiri, 2013). For example, according to this analysis, many of the trainers interviewed had not worked at SeaWorld for many years, and when they did, they were either not interacting with orcas at the time or were doing so under head trainer supervision (SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc., n.d.-a).

In advance of CNN’s airing of Blackfish, SeaWorld once again defended its record using controlled communication. To begin, SeaWorld released a statement to CNN prior to the network’s airing of the documentary in October 2013. In this statement, SeaWorld countered that

Blackfish is billed as a documentary, but instead of a fair and balanced treatment of a complex subject, the film is inaccurate and misleading…the film paints a distorted picture that withholds from views key facts about SeaWorld…the film fails to mention SeaWorld’s commitment to the safety of its team members and guests and to the care and welfare of its animals. (“SeaWorld Responds,” 2013, para. 2)

Then, in December 2013, SeaWorld published an open letter in major national newspapers, which placed direct emphasis on explaining its care of killer whales in the SeaWorld parks (see Appendix A). Additionally, this letter was launched on a new portion of its website under the killer whale section titled, “Truth About Blackfish.” A link to this section of the website was posted on SeaWorld’s Facebook page to reach a wider audience. In this letter, SeaWorld makes six statements about the killer whales under its care (SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc., n.d.-b):

- SeaWorld does not capture killer whales in the wild

- We do not separate killer whale mom and calves

- SeaWorld invests millions of dollars in the care of our killer whales

- SeaWorld’s killer whales’ life spans are equivalent with those in the wild

- The killer whales in our care benefit those in the wild

- SeaWorld is a world leader in animal rescue. (para. 9)

Social Media Response to Blackfish

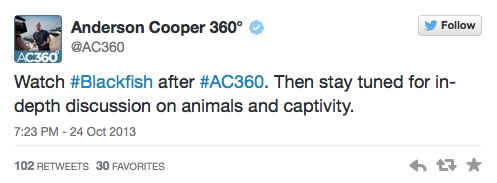

Blackfish garnered an astonishing amount of traditional and social media attention. This wave of negative attention towards SeaWorld seemed to drown out SeaWorld’s aforementioned communication efforts prior to the airings of Blackfish.

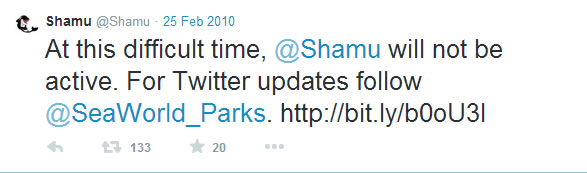

MediaMiser, a market research firm, created an infographic demonstrating the response to the film’s Sundance premier and the increasing anticipation for its CNN release (see Appendix B). According to MediaMiser (2015), between July 12 and August 16, 2013, the overall Twitter sentiment regarding SeaWorld was 74% negative (see Appendix B). Once CNN secured the broadcast rights to Blackfish, it began to brainstorm ways to leverage the growth of the conversation on Twitter, especially nearing the show’s premiere date. CNN invited users to join in on the conversation using the hashtag #Blackfish for the premiere broadcast.

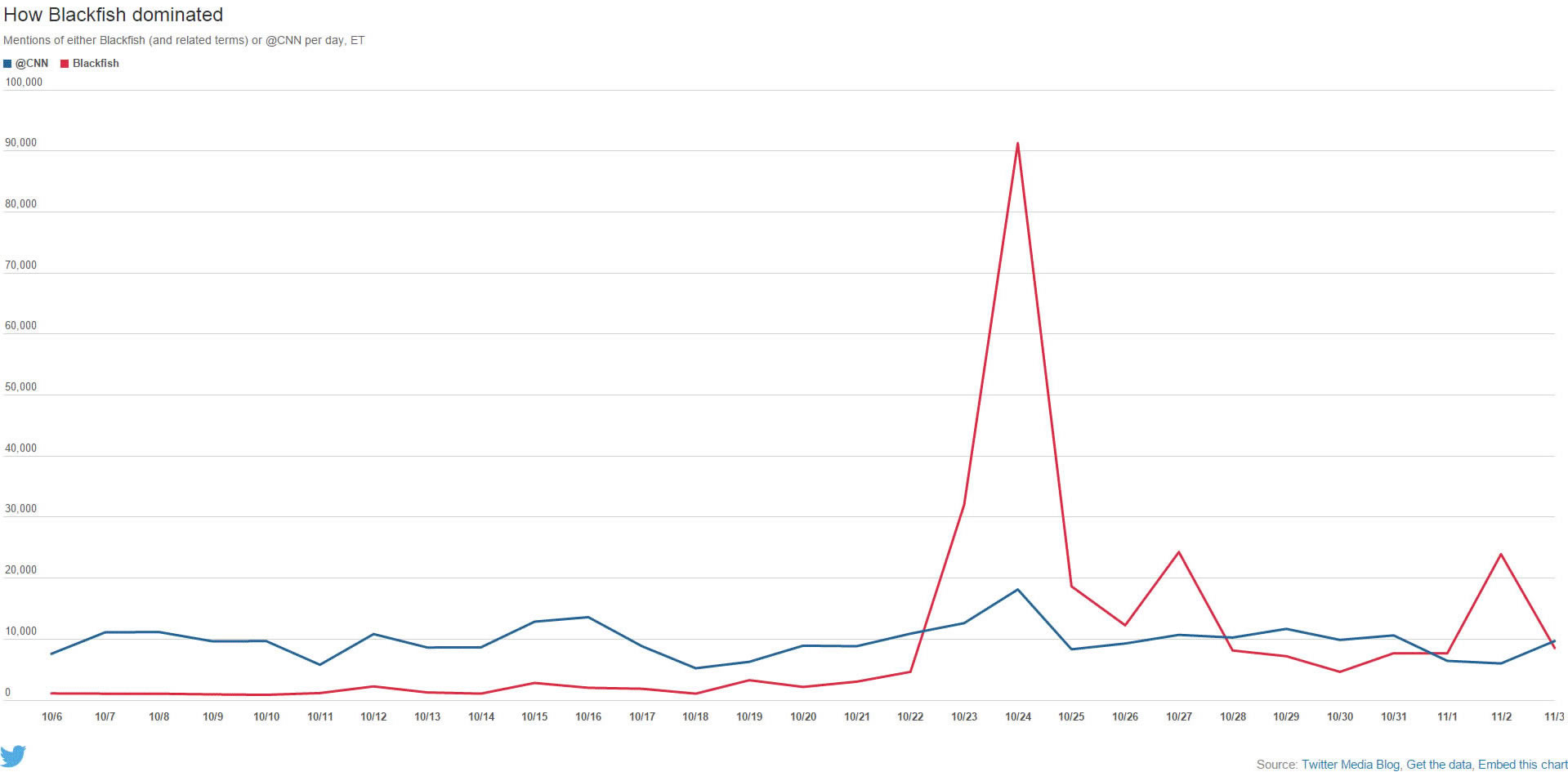

According to Twitter, there were 67,673 Tweets about Blackfish seen by 7.3 million people the night the film aired, making it the most talked about show on CNN in October 2013. Blackfish was also tweeted about more than any other non-sports program on TV except for the political thriller Scandal. CNN also integrated Twitter into the broadcast by displaying the #Blackfish hashtag on the screen throughout the broadcast and curating the unfolding Twitter conversation in a live CNN.com blog.

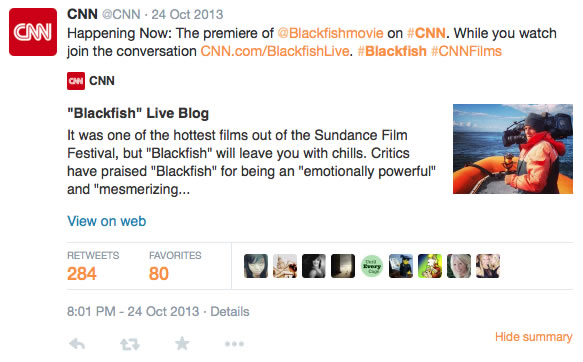

Leveraging CNN’s regular show Twitter accounts (see Figure 2) and a live post-show debate by CNN’s Anderson Cooper (see Figure 3) also expanded the conversation on social media (Rogers, 2013).

Figure 2. Tweet from @CNN account encouraging conversation on social media (Source: @CNN/CNN). Figure 3. Tweet from @AC360 promoting post-show debate on CNN (Source: @AC360/Anderson Cooper 360°).CNN’s tactics to promote #Blackfish also received support from celebrities. Ariana Grande, Zach Braff, Michelle Rodriguez and Stephen Fry are just a few of the actors who encouraged their followers to watch the documentary and think twice before visiting a SeaWorld park again. Activist groups like PETA took advantage of the social media interest in the broadcast. As shown on Figure 4, PETA encouraged followers to tweet with the hashtag #BlackfishOnCNN to create more buzz for the film (Rogers, 2013).

Figure 4. Tweet from @PETA encouraging use of the @BlackfishOnCNN hashtag (Source: @PETA/PETA).Another chart presented by Twitter (see Figure 5) demonstrates the amount of mentions between @CNN and Blackfish. Blackfish was mentioned 73,000 more times than @CNN the night the documentary aired. Twitter notes this is astonishing because @CNN is one of the largest online news accounts in the world (Rogers, 2013).

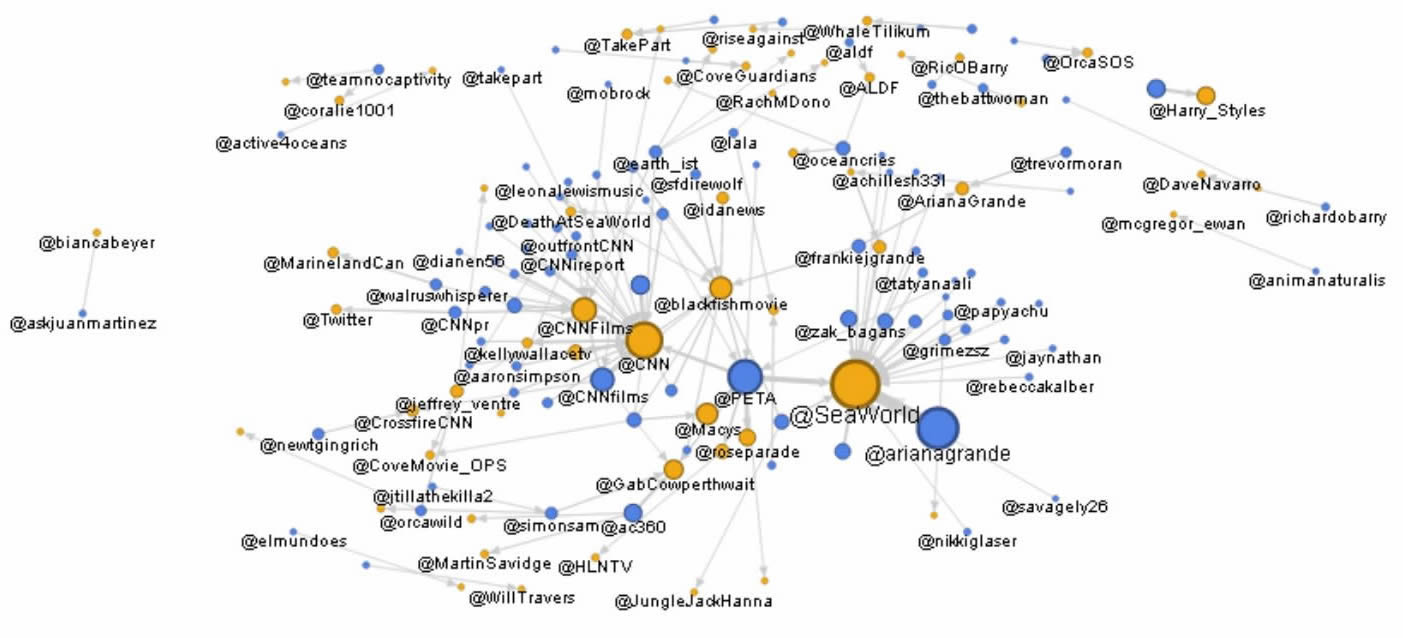

Figure 5. Mentions of “Blackfish” v. @CNN on Twitter in October 2013 (Source: Twitter Blog).Figure 6 was also compiled by Twitter and presents the most-mentioned Twitter accounts involved in the Blackfish discussion. SeaWorld was the most mentioned account, while PETA, CNN, CNNFilms and influential celebrity Ariana Grande (with 20.8 million Twitter followers at the time of the broadcast) followed behind (Rogers, 2013).

Figure 6. Most mentioned Twitter accounts in the “Blackfish” discussion (Source: Twitter Blog).It is important to note that several months after the airings of Blackfish on CNN, the family of Dawn Brancheau released a statement, informing the public that they were not involved nor affiliated with the creation of the documentary. The family also stated that Dawn believed in the ethical treatment of animals and would not have worked at SeaWorld if she did not believe the animals were treated fairly (Lee, 2014). This pro-SeaWorld statement—coming months later—received far less media attention.

Business Partner Response to Blackfish

SeaWorld’s initial business and strategic communication strategy for dealing with Blackfish seemed even more inadequate once a growing number of business partners chose to disassociate from the SeaWorld brand following the CNN broadcasts.

A series of entertainers cancelled their scheduled performances at SeaWorld theme parks. In late November 2013, Barenaked Ladies was the first band to announce they were pulling out of a show, with Willie Nelson and Heart following in their footsteps several weeks later. Joan Jett released a statement in December 2013 asking the park to discontinue the use of her hit song “I Love Rock ‘n’ Roll” during the “Shamu Rocks” show’s opening number (Schneider, 2013). Over the next few months, SeaWorld witnessed more performers backing out of commitments with the parks as a result of their feelings towards the treatment of orcas as portrayed in Blackfish.

Corporations associated with SeaWorld also felt the heat and some decided to discontinue their partnership arrangements with SeaWorld. For example, in May 2014, fast food chain Taco Bell came under fire by animal rights activists, such as PETA, for offering discounted tickets to SeaWorld. A Change.org petition was created and garnered more than 20,000 signatures (Morse, 2014). Taco Bell ultimately decided to cut ties with SeaWorld and ended its partnership in September 2014 (Cronin, 2014). Additionally, in July 2014, Southwest Airlines and SeaWorld announced the end of a promotional marketing relationship that had dated back to 1988 (Raab, 2014).

Other companies that chose to end their partnerships with SeaWorld include Virgin America, Alaska Air Group, Hyundai Motor Co., and Mattel (Messenger, 2014; Palmeri & Schlangenstein, 2014; Rooney, 2015).

Shift in Strategy and Tactics

SeaWorld made a major announcement in mid-August 2014 that indicated a substantial shift in its business and communication strategy and tactics from one of pure advocacy and defense to a blend of advocacy and accommodation (“After Film,” 2014). On August 15, 2014, SeaWorld unveiled an effort that demonstrated, through tangible actions, it was at least partially trying to accommodate stakeholder concerns. This three-part plan included the construction of what SeaWorld describes as a “first-of-its-kind killer whale environment” at SeaWorld San Diego, a pledge of $10 million in matching funds for killer whale research, and the formation of an independent advisory panel to provide new ideas and perspectives on the project (“SeaWorld Announces,” 2014, para. 1). While SeaWorld publicly unveiled these plans in mid-August 2014, it is unknown how long prior to this announcement these plans may have been in the works.

Called the Blue World Project, the new killer whale environment at SeaWorld San Diego will have a total water volume of 10 million gallons. This tank will be almost twice the size of the current tank, with a depth of up to 50 feet (“SeaWorld Announces,” 2014). SeaWorld says this new environment will include features that are more stimulating for the whales. It expects the new San Diego orca environment to open to the public in 2018, with similar environments following at SeaWorld Orlando and SeaWorld San Antonio (“SeaWorld Announces,” 2014). Consistent with the Blue World Project announcement, an October 2014 media report (Morton, 2014) indicates that SeaWorld San Antonio is embarking on a $30 million renovation, including new orca and dolphin habitats and a major renovation to this park’s sea lion attraction.

While the Blue World Project and related announcements were significant developments in SeaWorld’s response to Blackfish, these actions were not communicated aggressively to the public during the second half of 2014 through early 2015. Further, following the Blackfish eruption on social media, SeaWorld arguably lagged in its use of digital media to engage in dialogue with interested stakeholders regarding killer whale care and other issues. This finally changed in March 2015.

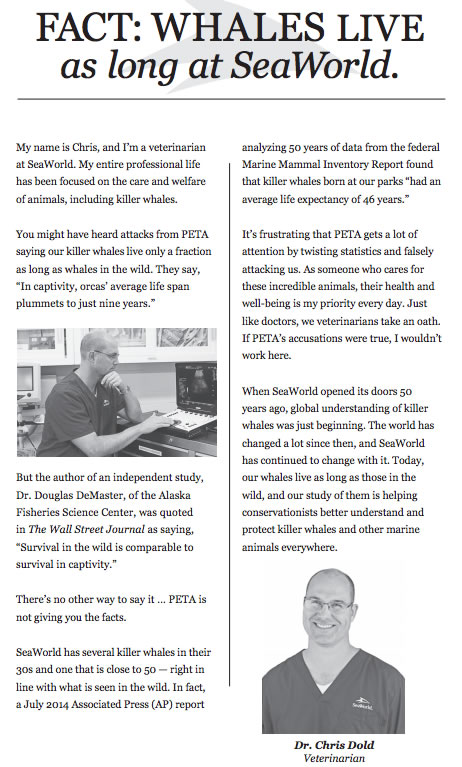

On March 23, 2015, SeaWorld announced the launch of a new reputation campaign geared at repairing its reputation and allowing the public the opportunity to make its own decisions about the company’s killer whale care (“SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc. Launches,” 2015; “New SeaWorld Advertising,” 2015). This campaign highlights the actions SeaWorld had already announced the previous summer related to the Blue World Project and conservation. The reputation campaign launched with print advertisements (see Figure 7) in elite national media (The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, Los Angeles Times) as well as in newspapers where SeaWorld parks are located. National television advertisements followed (see YouTube clip here).

Figure 7. Newspaper ad from SeaWorld’s reputation campaign (Source: SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc.).A new site, AskSeaWorld.com, serves as the hub for the digital components of SeaWorld’s reputation campaign (“SeaWorld has New Ad Campaign,” 2015). The public may ask SeaWorld questions using the #AskSeaWorld hashtag on social media, such as Twitter and Facebook, or directly at AskSeaWorld.com, SeaWorld’s YouTube channel, SeaWorldCares.com or SeaWorld.com/Truth; the company’s official responses are housed at AskSeaWorld.com. As of April 2015, SeaWorld says it has responded to 300 questions. Some of these questions are answered by SeaWorld employees in behind-the-scenes YouTube videos (“New SeaWorld Advertising,” 2015).

Jill Kermes, senior corporate affairs officer for SeaWorld, told The New York Times the following regarding the reputation campaign:

I think there’s been a lot of misinformation out in the public about who we are and what we do. It has been a one-sided conversation and this is an opportunity for us to give people the information they need so they can make up their own minds. (“SeaWorld Has New Ad Campaign,” 2015, para. 6)

SeaWorld continues to receive some criticism for its efforts, with Jared Goodman, director of animal law for activist group PETA, calling the campaign a “last ditch effort” (“SeaWorld Has New Ad Campaign,” 2015, para. 7). In turn, SeaWorld has blamed PETA for allegedly spamming its efforts on Twitter by trying to “deny people with real questions a chance to have their questions answered…70% of questions have come from PETA and other animal rights groups or bots” (Huston, 2015, para 4).

As of mid-2015, SeaWorld has spent $10 million on all of its efforts related to repairing its reputation and making its case (“SeaWorld Has New Ad Campaign,” 2015).

Evaluation

There are many ways an organization may measure and evaluate the success (or failure) of strategic communication campaigns or programs. Strategic communication research and measurement experts generally recommend that organizations measure the effects on business outcomes rather than simply communication outputs (Michaelson & Stacks, 2014; Stacks, 2010). Such outcome measures of business performance in the case of SeaWorld include the attendance at its theme parks, its financial performance (e.g., revenue and profits) and the performance of its stock price. While there are many possible indicators of business performance, these are three that are likely to have drawn the attention of SeaWorld’s C-suite and board during the multi-year Blackfish crisis.

As a reminder, Blackfish aired on CNN in the fall of 2013, sparking a sizable backlash and unrest among various stakeholder groups through 2014 (Ember, 2014). For full year 2014, SeaWorld Entertainment posted revenue of nearly $1.38 billion, a decline of 6% compared to 2013 revenue (SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc., 2015a). Profits for the year also declined with SeaWorld reporting net income of $49.9 million, down nearly 4% from the prior year (SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc., 2015a). SeaWorld blamed the declines in revenue and profits primarily on a -4.2% annual decline in attendance (22.4 million visitors to its parks in 2014 versus 23.4 million in 2013). Attendance at the SeaWorld San Diego park has been particularly affected by the negative media and activist attention (“SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc. Reports,” 2015).

SeaWorld’s stock price also significantly underperformed the broader market, with SeaWorld shares declining 38% in 2014, compared with a gain of 12% by the S&P 500 index, a broad gauge of U.S. stock market performance. The company’s year-end 2014 stock price of $17.90 represented a 34% fall from its IPO price of $27 in April 2013 (“SeaWorld Entertainment IPO,” 2013; “SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc. (SEAS) – Key Statistics,” 2015).

It should be noted that SeaWorld’s attendance and financial performance had been largely lackluster even prior to Blackfish (Greenfeld, 2014). However, SeaWorld management specifically spoke publicly about the Blackfish effect and negative media coverage on its financial performance. In its third quarter 2014 earnings conference call with investors, then SeaWorld CEO Jim Atchison, noted: “Clearly, 2014 has failed to meet our expectations” (“SeaWorld Entertainment’s (SEAS) CEO,” 2014, para. 9). Atchison went on to say in his prepared remarks on the earnings call:

We are adjusting our attraction and marketing plans to address our top line concerns primarily at our destination parks. These challenges include negative media attention in California and competitive pressures in Florida. On the reputation side, we have introduced a number of aggressive and proactive initiatives and campaigns to make sure the truth is being told, address public perceptions, and raise and protect brand awareness. (“SeaWorld Entertainment’s (SEAS) CEO,” 2014, para. 13)

Then SeaWorld Chief Financial Officer James Heaney shared similar remarks during this same quarterly earnings call. According to Heaney, “we believe the decline resulted from a combination of factors, including negative media attention in California along with the challenging competitive environment, particularly in Florida” (“SeaWorld Entertainment’s (SEAS) CEO,” 2014, para. 24). Heaney was specifically referring to proposed legislation in the state of California that would ban allowing orcas to be kept in captivity, thereby striking a direct blow at SeaWorld’s parks (Greenfeld, 2014).

Atchison emphasized SeaWorld’s commitment to overcoming these challenges, saying to investors:

I want you to know that our team is intensely focused on overcoming the short-term challenges we face and on improving our results; however, we recognize that we are in the early stages of these initiatives and the results we envision will take time to execute. (“SeaWorld Entertainment’s (SEAS) CEO,” 2014, para. 21)

Atchison resigned as CEO of SeaWorld in December 2014 (“SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc. Announces,” 2014), while Heaney resigned as CFO in May 2015 (“SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc. Appoints,” 2015).

There are preliminary signs that SeaWorld’s business reorganization and shift in communication strategy and tactics in mid-2014, followed by its 2015 reputation campaign and the continuation of these efforts, may be helping. For example, for the first half of 2015, SeaWorld reported attendance of 9.69 million compared with 9.63 million a year ago (“SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc. Reports,” 2015), at least not a decline. Revenue for the first half of 2015 was $606.2 million, down 2%, but cash flow from operating activities rose to $142.1 million, a 6% increase from $133.5 million a year ago (“SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc. Reports,” 2015).

SeaWorld’s stock price was flat year-to-date through the end of July 2015. SeaWorld’s stock price at the end of this stretch was basically where it started the year (“SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc. (SEAS) – Key Statistics,” 2015). While this slightly lagged behind the stock market’s 3% gain during this span, it still marked an improvement from its much worse underperformance in 2014. SeaWorld is by no means out of the woods, but these recent metrics indicate that the business may at least be stabilizing.

Analysis and Discussion

Shamu is known by many Americans, whether they have been to SeaWorld or not. For audiences to see a documentary that shows the potential harm and dangers of being an orca whale in an environment where these whales are said to be safe from all harm is emotional and heart wrenching. SeaWorld, a company whose theme parks have been visited by tens of millions and is known around the world for its marine animals, especially its splashy orca shows, has been placed between a rock and a hard place.

The release of Blackfish came at a bad time for SeaWorld. The company had recently gone public and its business was already showing signs of struggling to grow—even prior to the Blackfish brouhaha (Greenfeld, 2014). This case study suggests that SeaWorld management underestimated the potential impact of Blackfish on its reputation and business performance and seemed slow to respond. When it did, the scope of its response and the matching of words with real actions were lacking.

For example, in reviewing the required public filings that SeaWorld made with the SEC, it is notable that until May 2014, there was no meaningful discussion in its filings regarding the risks it was facing due to stakeholder-related blowback from Blackfish. This represents more than a year passing since the documentary first premiered at Sundance. This is a sign that SeaWorld was slow to appreciate—or at least acknowledge—the scope of this crisis on its business performance.

SeaWorld’s C-suite was notably shaken up in the two years following the Blackfish crisis with both its CEO and CFO resigning. Some could argue that SeaWorld’s handling of Blackfish further eroded shareholder confidence in this management team and accelerated changes at the top for the already struggling theme park operator. In March 2015, SeaWorld announced the appointment of Joel Manby as CEO (“SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc. Names,” 2015). Manby previously worked in the theme park industry and is known as a turnaround operator (Huddleston, 2015).

Casting aside one’s personal feelings about animals being kept in captivity, SeaWorld’s shift in communication strategy and tactics—and the effectiveness of such efforts (or lack thereof)—is instructive for strategic communication students and professionals. SeaWorld’s initial response to Blackfish (from before it premiered at Sundance to after its broadcasts on CNN) was defensive, seemed to take a purely advocacy stance, and almost exclusively used controlled strategic communication tactics (e.g., press statements and open letters/ads in newspapers). Then, more than six months later, in August 2014—seemingly an eternity in “social media years”—SeaWorld shifted the strategy for addressing its whale of a problem. The Blue World Project announcement of new killer whale environments at SeaWorld parks marked the first large scale action taken by SeaWorld in an attempt to accommodate concerns regarding orca welfare.

The ongoing reputation campaign by SeaWorld takes a quite different strategic communication approach than how the company first reacted to Blackfish. The new campaign still uses some controlled communication tactics (e.g., advertisements in newspapers and television commercials), but makes much more use of digital media to get across its positions, while also encouraging discussion from interested stakeholders via its social media channels. Further, this campaign highlights the tangible business actions SeaWorld has taken (e.g., its conservation and rescue track record) and is taking (e.g., its new killer whale environments) to support its claims regarding killer whale care.

For strategic communication students and professionals, this case offers several implications worth considering. First, never underestimate the ability of social media to galvanize an issue and rapidly build support, particularly when there is a potential trigger event lurking (in this case, the national broadcast of a documentary). Second, in an age of digital media and 24/7 news cycles, speed matters and the conversation will continue whether you join it and attempt to shape it or not. Third, words by themselves are just words. Communication is more believable and effective when it is grounded in actual organizational actions and policies that attempt to address stakeholder issues. Fourth, it takes money to protect money; organizations must be willing to devote the necessary resources to the strategic communication function to have their sides of the story told, particularly in times of crisis. SeaWorld has every right to defend itself in the court of public opinion, but such efforts are not cheap and the company seemed slow to spend. Finally, never underestimate an adversary on the other side of an issue. PETA and other animal activist groups proved particularly adept at working with and through the media.

At SeaWorld’s 2015 investor day in November 2015, it announced plans to phase out its signature Shamu show in the San Diego park by 2017. SeaWorld plans to launch an all-new informative experience that will provide guests with a “conservation message inspiring people to act” (Victor, 2015, para. 2). SeaWorld CEO Joel Manby emphasized the company’s attention to evolving customer expectations and highlighted that this decision was not due to activist criticism: “We didn’t do anything in San Diego because of the activists, we did it because we’re hearing from our guests” (Victor, 2015, para. 7). The end of the traditional killer whale shows at the San Diego park could particularly benefit two other stakeholder groups, the local business community and park employees, who have been negatively affected by the media and activist attention.

The future for SeaWorld remains hazy. The issue of animal welfare in its parks, particularly keeping killer whales in captivity, is not likely to go away. Blackfish is easily viewable on demand from Netflix and other sources. Even a decade later, there are still references in the media to Super Size Me, a documentary that was highly critical of McDonald’s, and this was before social media was as pervasive as it is today. Further, PETA and other animal welfare activist groups are not likely to back down, particularly since there are signs that public opinion has moved in their direction, not just when it comes to SeaWorld and killer whales, but in other cases involving animals in captivity.

For example, after decades of battles with animal welfare activists, Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey circus made a surprise announcement in March 2015 that it would eliminate elephants from its circus performances by 2018 (“Ringling Bros. Says,” 2015). The “retired” elephants will live out their years at a Ringling-owned elephant conservation center in central Florida. Field Entertainment, the owner of Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey, denies that its elephants are mistreated in any way, but seems to have grown tired battling activists, anti-circus legislation, and a general shift in public opinion on circus elephants as performers (Davis, 2015; “Ringling Bros. Says,” 2015).

While SeaWorld’s recent financial results suggest that its business may be stabilizing, the business is not growing meaningfully either; it may need to take more drastic actions over its killer whale issue. Some stakeholders are still choosing to part ways with SeaWorld or take issue with its business practices. For example, in April 2015, Mattel announced that it was ending production of all SeaWorld-branded merchandise, including SeaWorld trainer Barbies (Kosman, 2015). In May 2015, the California Division of Occupational Safety and Health issued several citations to SeaWorld San Diego, determining the company was not adequately protecting its killer whale trainers at this park (“SeaWorld Cited,” 2015). Finally, in November 2015, the California Coastal Commission, a state regulatory agency, attached a condition to its approval of SeaWorld’s Blue World Project expansion plans that would ban orca breeding at the park (Daniels, 2015). SeaWorld says this ruling calls into question the project’s viability.

Animal rights groups like PETA and others have argued that SeaWorld should cease entirely having killer whale shows and the breeding of orcas in captivity (DiPietro, 2015). Such groups have argued that these orcas should be returned to the wild if possible and to “sea pens” or netted-off bays or coves if not (Steinmetz, 2014). SeaWorld’s business model as it relates to marine mammals would move away entirely from shows of any kind, and more towards wildlife sanctuaries and education centers (Steinmetz, 2014).

At least publicly, SeaWorld still seems somewhat resistant to such options. In response to a question on the SeaWorldCares.com site, SeaWorld says that its “killer whales are thriving right where they are and millions of people get to see them and be inspired by them every year” and its facilities “are among the largest and most sophisticated in the world and we are committed to nearly doubling their size” (SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc., 2015c, para. 1). Of course, Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus was also publicly resistant to removing elephants from its shows up until it surprised the public with its monumental announcement (“Ringing Bros. Says,” 2015).

There are no easy decisions ahead for new SeaWorld CEO Joel Manby, his management team and the strategic communication professionals that work on behalf of SeaWorld. Manby has said that SeaWorld will remain vigilant in supporting its brands and “communicating the facts, which are on our side” (SeaWorld Entertainment, 2015c, para. 6). This does not sound like someone planning to fully “free Shamu” anytime soon, but if stakeholder support keeps eroding, SeaWorld one day may be forced to do so.

Discussion Questions

- If you were working for or with SeaWorld’s strategic communication team, how would you have responded initially to the allegations cited in the documentary? Be specific in describing your recommended communication strategy and tactics.

- Why do you believe SeaWorld decided to shift its business and communication strategy and tactics months after the airing of Blackfish on CNN? What do you think of SeaWorld’s announcement that it will end its traditional orca shows at the SeaWorld San Diego park? Should it end the shows at its other two parks as well?

- Do you believe that SeaWorld’s reputation campaign will have the desired effect of strengthening the company’s reputation and improving its relationship with stakeholders, particularly customers and business partners? Why or why not? What do you think of the tactics being used in this campaign?

- After a century of elephants being part of the circus, Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey announced in 2015 that its elephants would “retire” and no longer perform. If you worked on SeaWorld’s strategic communication team, would you recommend the company take a similar action and “retire” its killer whales?

- Put yourselves in the shoes of PETA and animal welfare activist groups. How would you rate their performance in leveraging the release of the Blackfish documentary and its airings on CNN? If you were working in strategic communication on behalf of PETA post-Blackfish, what should be the strategy and tactics used to keep the pressure on SeaWorld and its stakeholders?

Activity

Have students break up into two groups. Pretend it is summer 2013. SeaWorld has just learned that CNN has secured the broadcast rights to Blackfish. Each group will take 30 minutes to create a mock crisis communication plan for SeaWorld in response to activist groups such as PETA supporting and communicating the allegations presented in the Blackfish documentary broadcasts on CNN. Each group will then present their plan and class discussion will highlight each plan’s strengths and areas for improvement.

References

After film, Sea World to make improvements. (2014, August 15). The Associated Press. Retrieved July 14, 2015, from http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/16/business/after-film-seaworld-to-make-improvements.html?r=1

Cowperthwaite, G., Oteyza, M. V. (Producers), & Cowperthwaite, G. (Director). (2013). Blackfish [Motion picture]. United States: Magnolia Pictures.

Cronin, M. (2014, May 21). Taco Bell severs ties with SeaWorld amid “Blackfish” backlash. The Dodo. Retrieved July 13, 2015, from https://www.thedodo.com/taco-bell-severs-ties-with-sea-560203119.html

Daniels, J. (2015, November 9). SeaWorld phasing out Shamu show in San Diego. CNBC. Retrieved December 16, 2015, from http://www.cnbc.com/2015/11/09/seaworld-to-talk-strategy-as-attendance-declines.html

Davis, J. M. (2015, March 7). A bittersweet bow for the elephant: Ringling Brothers will retire its elephants, and an American tradition. The New York Times. Retrieved July 14, 2015, from http://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/08/opinion/sunday/ringling-brothers-will-retire-its-elephants-and-an-american-tradition.html

Eberi, B. (2013, July 19). SeaWorld fights back at the critical documentary ‘Blackfish.’ Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved July 13, 2015, from http://www.bloomberg.com/bw/articles/2013-07-19/seaworld-fights-back-at-the-critical-documentary-blackfish

Greenfeld, K. T. (2014, December 12). SeaWorld dumps its CEO: Don’t just blame Blackfish. Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved July 14, 2014, from http://finance.yahoo.com/news/seaworld-dumps-ceo-dont-just-032013724.html

Hare, B. (2013, October 29). ‘Blackfish’: A chilling doc on captive killer whales. CNN. Retrieved July 13, 2015, from http://www.cnn.com/2013/07/12/showbiz/movies/blackfish-documentary-exclusive-clip/

Huddleston, T. (2015, March 19). Struggling SeaWorld reels in theme park vet to fill CEO vacancy. Fortune. Retrieved July 26, 2015, from http://fortune.com/2015/03/19/seaworld-hires-joel-manby-ceo/

Huston, C. (2015, March 30). SeaWorld blames PETA for spamming its outreach campaign. MarketWatch. Retrieved July 12, 2015, from http://www.marketwatch.com/story/seaworld-blames-peta-for-spamming-its-outreach-campaign-2015-03-30

Kirchfeld, A. (2012, December 27). Blackstone’s SeaWorld files for initial share sale in U.S. Bloomberg News. Retrieved July 13, 2015, from http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-12-27/seaworld-files-for-initial-share-sale-as-blackstone-seeks-cash.html

Kosman, J.(2015). ‘Seaworld’ Barbie sleeps with the fishes. New York Post. Retrieved August 2, 2015, from http://nypost.com/2015/04/23/seaworld-barbie-sleeps-with-the-fishes/

Kuo, V., & Savidge, M. (2014, February 9). Months after ‘Blackfish’ airs, debate over orcas continues. CNN. Retrieved July 23, 2015, from http://www.cnn.com/2014/02/07/us/blackfish-wrap/

Lee, J. J. (2014, January 22). Family of SeaWorld trainer killed by orca speaks out for first time. National Geographic. Retrieved July 13, 2015, from http://voices.nationalgeographic.com/2014/01/22/family-of-seaworld-trainer-killed-by-orca-speaks-out-for-first-time/

MediaMiser Ltd. (2015). #Blackfish vs. #SeaWorld. Mediamiser.com. Retrieved July 13, 2015, from http://www.mediamiser.com/blog/infographics/blackfish-vs-seaworld/

Messenger, S. (2014, November 14). Hyundai Motor cuts ties with SeaWorld. The Dodo. Retrieved July 14, 2015, from https://www.thedodo.com/hyundai-cuts-ties-seaworld-819812155.html

Michaelson, D., & Stacks, D. W. (2014). A professional and practitioners’ guide to public relations research, measurement and evaluation (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Business Expert Press.

Morse, L. (2014, April 23). Why is Taco Bell supporting SeaWorld animal abuse? Change.org. Retrieved July 14, 2015, from https://www.change.org/p/why-is-taco-bell-supporting-seaworld-animal-abuse

Morton, N. (2013, April 19). SeaWorld makes a splash on the NYSE. mySA. Retrieved July 22, 2015, from http://www.mysanantonio.com/business/article/SeaWorld-makes-a-splash-on-the-NYSE-4448137.php#photo-4500297

Morton, N. (2014, October 24). SeaWorld San Antonio moves forward with expansion plans. mySA. Retrieved July 14, 2015, from http://www.mysanantonio.com/business/eagle-ford-energy/article/SAN-ANTONIO-SeaWorld-San-Antonio-moves-5845465.php

New SeaWorld advertising campaign highlights leadership in killer whale care, counters misinformation [Press release]. (2015, March 23). Seaworldinvestors.com. Retrieved July 29, 2015, from http://www.seaworldinvestors.com/files/doc_news/New-SeaWorld-Advertising-Campaign-Highlights-Leadership-In-Killer-Whale-Care-Counters-Misinformation.pdf

Palmeri, C., & Schlangenstein, M. (2014, October 31). Virgin America drops SeaWorld in next blow to orca parks. Bloomberg News. Retrieved July 14, 2015, from http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2014-10-14/virgin-america-drops-seaworld-in-next-blow-to-orca-parks

People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals [PETA]. (2011, October 25). PETA sues SeaWorld for violating orcas’ constitutional rights. PETA.org. Retrieved July 13, 2015, from http://www.peta.org/blog/peta-sues-seaworld-violating-orcas-constitutional-rights/

Raab, L. (2014, July 31). Southwest, SeaWorld end partnership a year after ‘Blackfish’ backlash. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 14, 2015, from http://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-seaworld-southwest-airlines-20140731-story.html

Ringling Bros. says circuses to be elephant-free in 3 years (2015, March 6). The New York Times. Retrieved July14, 2015, from http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2015/03/06/us/ap-us-ringling-bros-circus-elephants.html

Rogers, S. (2013, November 6). The #Blackfish phenomenon: A whale of a tale takes over Twitter. Twitter Blog. Retrieved December 31, 2015, from https://blog.twitter.com/2013/the-blackfish-phenomenon-a-whale-of-a-tale-takes-over-twitter

Rooney, B. (2015, April 24). Mattel ends SeaWorld-themed Barbie toys. Orcas applaud. CNN Money. Retrieved July 26, 2015, from http://money.cnn.com/2015/04/24/news/mattel-barbie-seaworld/

Schneider, M. (2013, December 9). Heart, Barenaked Ladies, Willie Nelson all cancel SeaWorld gig after ‘Blackfish.’ The Huffington Post. Retrieved July 13, 2015, from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/12/09/heart-barenaked-ladies-willie-nelson-seaworld_n_4414666.html

SeaWorld announces first-of-its-kind killer whale environment and more than $10 million in new funding for research and conservation projects [Press release]. (2014, August 15). Seaworldentertainment.com. Retrieved July 14, 2015, from http://seaworldentertainment.com/en/media/company-news/blue-world-project

SeaWorld cited over killer-whale trainer safety. (2015, May 1). The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved July 12, 2015, from http://www.wsj.com/articles/seaworld-cited-over-killer-whale-trainer-safety-1430515350

SeaWorld credit rating, stocks plummet in response to Blackfish. (2014, August 14). The Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 14, 2015, from http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/chi-seaworld-blackfish-credit-stocks-tank-20140814-story.html

SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc. announces David D’Alessandro named interim CEO [Press release]. (2014, December, 11). Seaworldinvestors.com. Retrieved July 14, 2015, from http://www.seaworldinvestors.com/files/doc_news/SeaWorld-Entertainment-Inc-Announces-David-DAlessandro-Named-Interim-CEO.pdf

SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc. appoints Marc G. Swanson as interim CFO [Press release]. (2015, May 26). Seaworldinvestors.com. Retrieved July 23, 2015, from http://www.seaworldinvestors.com/files/doc_news/SeaWorld-Entertainment-Inc-Appoints-Marc-G-Swanson-as-Interim-CFO.pdf

SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc. launches national television advertising campaign highlighting its commitment to killer whale care [Press release]. (2015, April 6). Seaworldinvestors.com. Retrieved July 30, 2015, from http://www.seaworldinvestors.com/files/doc_news/SeaWorld-Entertainment-Inc-Launches-National-Television-Advertising-Campaign-Highlighting-Its-Commitment-To-Killer-Whale-Care.pdf

SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc. names Joel Manby as president and CEO [Press release]. (2015, March 19). Seaworldinvestors.com. Retrieved July 14, 2015, from http://www.seaworldinvestors.com/news-releases/news-release-details/2015/SeaWorld-Entertainment-Inc-Names-Joel-Manby-As-President-And-CEO/default.aspx

SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc. reports second quarter 2015 results [Press release]. (2015, August 6). Seaworldinvestors.com. Retrieved August 16, 2015, from http://www.seaworldinvestors.com/files/doc_news/2015-Q2-Earnings-Release-IR-Website.pdf

SeaWorld Entertainment IPO raises $702 million. (2013, April 19). CNBC.com. Retrieved July 22, 2015, from http://www.cnbc.com/id/100655244

SeaWorld Entertainment’s (SEAS) CEO, Jim Atchison on Q3 2014 results – earnings call transcript. (2014, July 14). SeekingAlpha.com. Retrieved July 22, 2015, from http://seekingalpha.com/article/2674225-seaworld-entertainments-seas-ceo-jim-atchison-on-q3-2014-results-earnings-call-transcript

SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc. (n.d.-a). ‘Blackfish’ analysis: Misleading and/or inaccurate content. Retrieved July 13, 2015, from http://da15bdaf715461308003-0c725c907c2d637068751776aeee5fbf.r7.cf1.rackcdn.com/adf36e5c35b842f5ae4e2322841e8933_4-4-14-updated-final-of-blacklist-list-of-inaccuracies-and-misleading-points.pdf

SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc. (n.d.-b). SeaWorld: The truth is in our parks and people. An open letter from SeaWorld’s animal advocates. Seaworldcares.com. Retrieved July 13, 2015, from http://seaworldcares.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Engish_Letter.pdf?from=Top_Nav

SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc. (2015a). Form 10-K 2014. Retrieved July 14, 2015, from http://d1lge852tjjqow.cloudfront.net/CIK-0001564902/79ad783d-f096-42f8-9370-a33ddcb4ed36.pdf?noexit=true

SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc. (2015b). How we care. Seaworldentertainment.com. Retrieved July 13, 2015, from http://seaworldentertainment.com/en/how-we-care/welcome

SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc. (2015c). Shareholders letter 2014. Retrieved July 14, 2015, from http://www.seaworldinvestors.com/files/OAR/2014/

SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc. (2015d). Truth about Blackfish. Seaworldcares.com. Retrieved http://seaworldcares.com/the-facts/truth-about-blackfish/

SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc. (2015e). Who we are. Seaworldentertainment.com. Retrieved July 13, 2015, from http://seaworldentertainment.com/en/who-we-are/history

SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc. (2015f). Why won’t SeaWorld consider moving its killer whales to sea pens? SeaWorldCares.com. Retrieved August 2, 2015, from http://ask.seaworldcares.com/?p=278

SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc. (2015g). Wildlife rescue. Seaworldentertainment.com. Retrieved July 13, 2015, from http://seaworldentertainment.com/en/how-we-care/wildlife-rescue/?from=Top_Nav

SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc. (SEAS) – key statistics (2015). Yahoo! Finance. Retrieved July 14, 2015, from http://finance.yahoo.com/q/ks?s=SEAS+Key+Statistics

SeaWorld has new ad campaign after disparaging documentary. (2015, March 23). The New York Times. Retrieved July 12, 2015, from http://nyti.ms/1EJMc0n

SeaWorld responds to questions about captive orcas, ‘Blackfish’ film. (2013, October 28). CNN. Retrieved from http://www.cnn.com/2013/10/21/us/seaworld-blackfish-qa/index.htmlcontent/uploads/2015/05/Engish_Letter.pdf?from=Top_Nav

Secretary of Labor v. SeaWorld of Florida, LLC. (2011). Atlanta, GA: Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission. Retrieved July 29, 2015, from https://web.archive.org/web/20120608211034/http://www.oshrc.gov/foia/SecLabSeaWorld/Sea-World_ALJ.pdf

Spears, L. (2013, April 18). SeaWorld raises $702 million in IPO, pricing at top of range. Bloomberg News. Retrieved July 13, 2015, from http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-04-19/seaworld-raises-702-million-in-ipo-pricing-at-top-of-range

Stacks, D. W. (2010). Primer of public relations research (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Steinmetz, K. (2014, April 8). SeaWorld will keep its orcas for at least another year. TIME. Retrieved August 2, 2015, from http://time.com/54096/sea-world-killer-whale-blackfish-bill

Sundance Institute. (2014). 30 years of Sundance film festival. Sundance.org. Retrieved July 13, 2015, from http://www2.sundance.org/festivalhistory/

US Labor Department’s OSHA cites SeaWorld of Florida following animal trainer’s death [Press release]. (2010, August 23). United States Department of Labor website. Retrieved July 13, 2015, from https://www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=NEWS_RELEASES&p_id=18207

Victor, D. (2015, November 9). Killer whales to take final bows at SeaWorld San Diego. The New York Times. Retrieved December 17, 2015, from http://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/10/business/seaworld-san-diego-killer-whales-shamu-show.html

Zelman, J. (2012, February 9). PETA’s SeaWorld slavery case dismissed by judge. The Huffington Post. Retrieved July 13, 2015, from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/02/09/peta-seaworld-slavery-_n_1265014.html

STEFANI DUHON, M.A., wrote and published this paper as part of her studies at DePaul University while receiving her Master of Arts in 2015. She now works for Ketchum, a global public relations firm. Email: Stefani.Duhon[at]gmail.com.

KELLI ELLISON is a graduate student in the M.A. in public relations and advertising program at DePaul University. She is a customer success manager at the Chicago headquarters of CareerBuilder. Email: elliso57[at]gmail.com.

MATTHEW W. RAGAS, Ph.D., is an associate professor and academic director of the public relations and advertising graduate program in the College of Communication at DePaul University. He earned his Ph.D. from the University of Florida. Email: mragas[at]depaul.edu.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the dedication, enthusiasm, and spirit of inquiry among the students in the Fall 2014-2015 Corporate Communication graduate seminar at DePaul University. This course inspired the initial development of this case study, as well as several winning entries into the 2015 Arthur W. Page Society case study competition in corporate communication.

Editorial history

Received August 16, 2015

Revised January 12, 2016

Accepted February 25, 2016

Published June 3, 2016

Handled by editor; no conflicts of interest

Appendix A. SeaWorld’s open letter to the public (Source: SeaWorld Entertainment, Inc.).

Appendix B. MediaMiser’s #Blackfish v. #SeaWorld infographic (Source: MediaMiser Ltd.).