To cite this article

Ciszek, E. (2016). A corporate coming out: Crisis communication and engagement with LGBT publics. Case Studies in Strategic Communication, 5, article 5. Available online: http://cssc.uscannenberg.org/cases/v5/v5art5

Access the PDF version of this article

| Special Section |

| Breaking the Rules |

|---|

A Corporate Coming Out: Crisis Communication and Engagement with LGBT Publics

Erica Ciszek

University of Houston

Abstract

In light of the legalization of same-sex marriage in the United States in June 2015, this case study provides a historical examination of one of the first corporate engagements with lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) publics. In this case, readers are presented with a historical case of crisis communication and LGBT publics, with examples that demonstrate how an organization can turn a moment of crisis and organizational mishandling to become a corporate leader in LGBT relations. At a time when public opinion toward LGBT people and issues was low, American Airlines broke social and economic rules with game-changing strategic communication. Key findings from this research demonstrate the importance of understanding internal and external publics, ethically engaging with marginalized publics, and setting the course for exemplary relations with marginalized publics. The American Airlines case serves as an example of spurring new research questions and new ways of thinking about strategic communication and LGBT issues and publics.

Keywords: crisis communication; crisis management; activist relations; community relations; employee relations

Introduction

Occasionally organizations encounter backlash from activists that shake the philosophical foundation of an institution. Sometimes these interactions with activists lead to crises that result in organizational soul researching, causing management and communications teams to rethink existing policies and procedures. At times these moments become game changers, whereby organizations engage in risky relationships and edgy communication and establish new industry trends. Fitting with the theme of this special section, “Breaking the Rules,” this case study examines two game-changing incidents American Airlines faced that proved transformative and forward-thinking.

Since 1994, American Airlines has been a leader in its commitment to lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) employees and customers. AA was the first major airline to implement sexual orientation (1993) and gender identity (2001) in workplace nondiscrimination policies and was the first major airline to have a company-recognized LGBT employee resource group. In 2000, it became the first major airline to offer same-sex domestic partner benefits and endorse the Employment Non-Discrimination Act (2008). American Airlines is the first Fortune 100 company to develop a gay and lesbian national marketing and sales team—the Rainbow TeAAm—that works with local and national LGBT community groups to plan travel. AA is a founding corporate member of the National Gay and Lesbian Chamber of Commerce, as well as the first and only airline today to include LGBT-owned businesses in its supplier diversity program.

American Airlines has not always had a harmonious relationship with LGBT publics, however, and in the early 1990s experienced two major crises, propelled by LGBT activists, that caused the organization to reexamine its policies and procedures. This case study is an examination of American’s crisis response during these incidents and the ensuing corporate strategy that positioned American Airlines as a corporate leader in LGBT equity and inclusion for the past 20 years.

Crisis, as defined by current literature, is a specific, unexpected event that can potentially damage an organization’s reputation, image, material resources, relationships, and profits (Coombs, 1999; Fearn-Banks, 2001; Seeger, Sellnow, & Ulmer, 2001; Ulmer et al., 2007). Crisis can be onset by a variety of factors and can become a defining moment for an organization. Moments of crisis play a pivotal role in an organization’s relationship with stakeholders. Crisis situations are not only obstacles to overcome, but also are events that can provide an organization with an opportunity to strengthen practices and reputation in the eyes of stakeholders (Wrigley, Salmon, & Park, 2003). Coombs and Holladay (2001) argue that an organization’s relational history with its stakeholders plays an important role in its performance history. One such stakeholder group is activist publics.

Activism has played a central role in the development of public relations (Smith, 2005). Smith and Ferguson (2001) argue, “the relationship between activists and organizations is tenuous, and the history of conflict between these two entities suggests that much can be learned from studying activism and responses to it” (p. 291). This present case study examines how American Airlines responded to LGBT publics and activists in ways that were groundbreaking for corporations and paved the way for building relationships with internal and external LGBT publics.

Practitioners and scholars of public relations have been considering crisis communication and activism for some time. Activism is the exertion of pressure by groups of people on organizations or other institutions to “change policies, practices, or conditions” activists find problematic (Smith, 2005, p. 5). Activists work to influence public policy, organizational action, and social norms and values (Smith, 1997), employing a variety of strategies and tactics to get on organizational and public agendas (Rochon, 1988) in order to produce social change (den Hond & de Bakker, 2007). Activists identify and aim to rectify a situation by drawing attention to a problem, legitimizing themselves as advocates, and successfully arguing for resolution to the issue (Crable & Vibbert, 1985; Heath, 1997; Vibbert, 1987).

Understanding why and when activists act is important (Rowley & Moldoveanu, 2003) and is considered critical to public relations practice and scholarship (Smith & Ferguson, 2001). But as public relations practitioners it is important to consider how organizations respond to activists and the social, cultural, and economic implications of such responses. Although some scholars suggest that organizations can ignore particular activists (Dougall, 2006), this case study suggests how organizations can work with activists to revise policies and procedures in order to develop best practices.

Background

The 1960s was an era for new social movements including women’s liberation, anti-war activism, environmentalism, youth suffrage, and civil rights. Toward the end of the decade, the gay liberation[1] movement emerged, bringing sexual orientation and discrimination to light. LGBT people were often the victims of physical violence and discrimination, including police brutality. During this time period, police officers often raided LGBT hangouts. On June 28, 1969, the New York City police raided the Stonewall Inn, a bar that catered to marginalized people of the gay community including drag queens, transgender people, effeminate men, butch lesbians, male prostitutes, and homeless youth (Duberman, 1993). Bar patrons resisted police and rioted in the streets for six days, and although LGBT resistance to police occurred throughout the 1960s, the 1969 Stonewall Riots are marked as a historical moment for the LGBT movement. Thousands of people were involved and the riots were the first to get major media coverage (Carter, 2009). Stonewall, therefore, was considered the “birth of gay pride” (LaFrank, 1999, p. 21).

One year later, the first Gay Pride marches were held in New York City, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Chicago to commemorate the anniversary of the riots. Following Stonewall, several LGBT organizations emerged including the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) and the Gay Activists’ Alliance (GAA), characterizing the following decade with organized activism that came to be known as the gay liberation movement.

Throughout the 1970s, LGBT activists worked to bring awareness to structural and institutional inequality. The introduction of HIV/AIDS, however, brought in a new wave of activism among the LGBT community. During the late 1980s and early 1990s, the LGBT community was plagued by an epidemic that wiped out an entire generation of gay men. Although AIDS quickly became a national health crisis that “decimated” (Morris, 2015, para. 8) the gay community, governmental institutions largely ignored AIDS (Rimmerman, 2002) and the LGBT people it disproportionately affected.

In response to the deafening silence, on October 1987, hundreds of thousands of activists participated in the National March on Washington, demanding President Ronald Reagan address the AIDS crisis. Although AIDS had first been reported in 1981, it wasn’t until the end of his term that Reagan spoke publicly about epidemic (“Milestones,” n.d.).

The “Pillows and Blankets” Episode

Activists gathered in Washington, D.C., once again on April 25, 1993, for the March on Washington for LGBT Equal Rights and Liberation. They organized demonstrations, rallies, celebrations, and lobbied lawmakers for equal rights for LGBT people, but again to demand attention to the HIV/AIDS crisis.

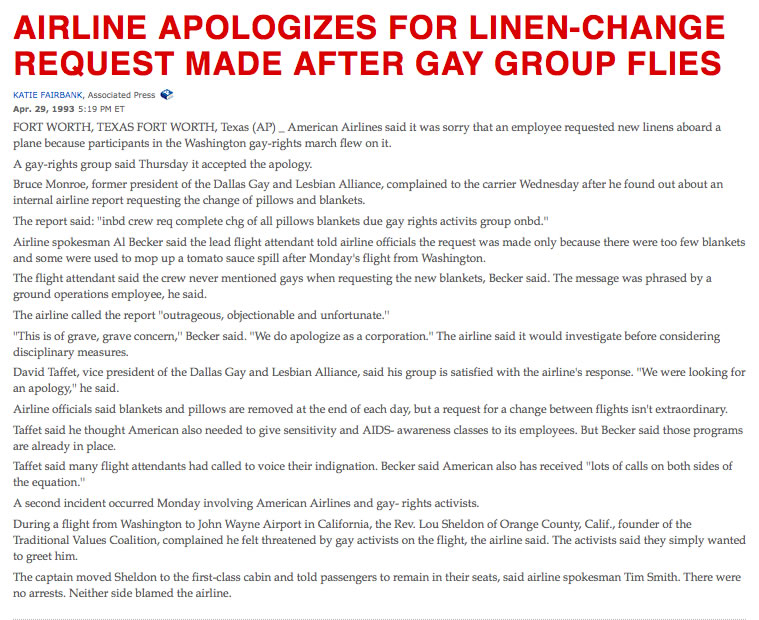

Many of these activists flew to and from Washington, D.C., to participate. On one particular post-march American Airlines flight bound for Dallas-Fort Worth, a situation erupted when a member of the flight crew sent an electronic message to the airline’s operations center requesting a change of pillows and blankets due to the number of activists on board returning from the march. The ground crew received a message, transcribed as: “inbd crew req complete chg of all pillows blankets due gay rights activists group onbd” (Fairbank, 1993, para. 4).

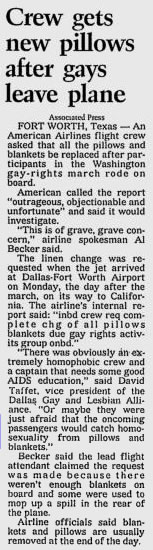

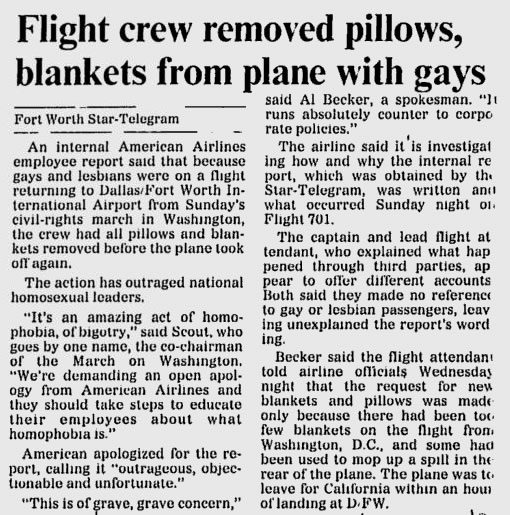

The internal memo was soon leaked to media outlets through an Associated Press Newswire (see Figure 1), and the mainstream media began to cover the incident (see Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 1. Associated Press Newswire of pillows and blankets incident (April 29, 1993). Figure 2. AP article appearing in the April 29, 1993, issue of the Moscow-Pullman Daily News (Moscow, ID). Figure 3. A Fort Worth Star-Telegram article appearing in the April 29, 1993, issue of The Day (New London, CT).The situation unfolded. American Airline’s Chief of Corporate Communications at the time, Tim Doke, noted:

The first indication I had that we might have an explosive issue was seeing one of my colleagues standing in my doorway, holding a faxed copy of a message sent to our office from the Associated Press. It shattered our disbelief when they called and said they had received a message sent from one of our airplanes to the DFW ground ops center. Someone clearly sent this message directly to the media to seize our attention. It worked! (Witeck & Kincaid, 2011a, p. 3)

American Airlines had a major situation on their hands. Doke added: “Someone observed that we likely had thousands, perhaps tens of thousands of gay employees. Someone else added that we also likely had hundreds of thousands of gay customers” (Witeck & Kincaid, 2011a, p. 4). This incident troubled Chairman and President Robert Crandall, who insisted AA did not discriminate against gay people. The legal team, however, informed Crandall the airline did not actually have a policy prohibiting the discrimination of gays and lesbians.

The IV Incident

Several months later, on November 14, 1993, Timothy Holless, a visibly frail passenger who appeared to be in late-stages of AIDS-related illness, was removed from an American Airlines flight. While on board, the passenger attempted to administer medication intravenously, against instruction from flight crew. The passenger violated American Airlines’ general medical policy at the time, which noted that IV could only be administered on board by qualified medical professionals. After contacting American Airlines’ operations center and corporate medical offices, crewmembers asked the passenger to leave the aircraft, but the passenger refused to move or discontinue the IV. The passenger noted that he would not leave the plane unless he was physically removed or arrested. Crewmembers called local police and the passenger was forcibly removed from the plane and escorted back to the terminal by four officers. Another passenger described the scene as police dragged Holless off the plane, face-down on his stomach as he screamed “Chicago police abuse” (Gallagher, 1993, p. 31). Coincidentally, the local news media captured the moment.

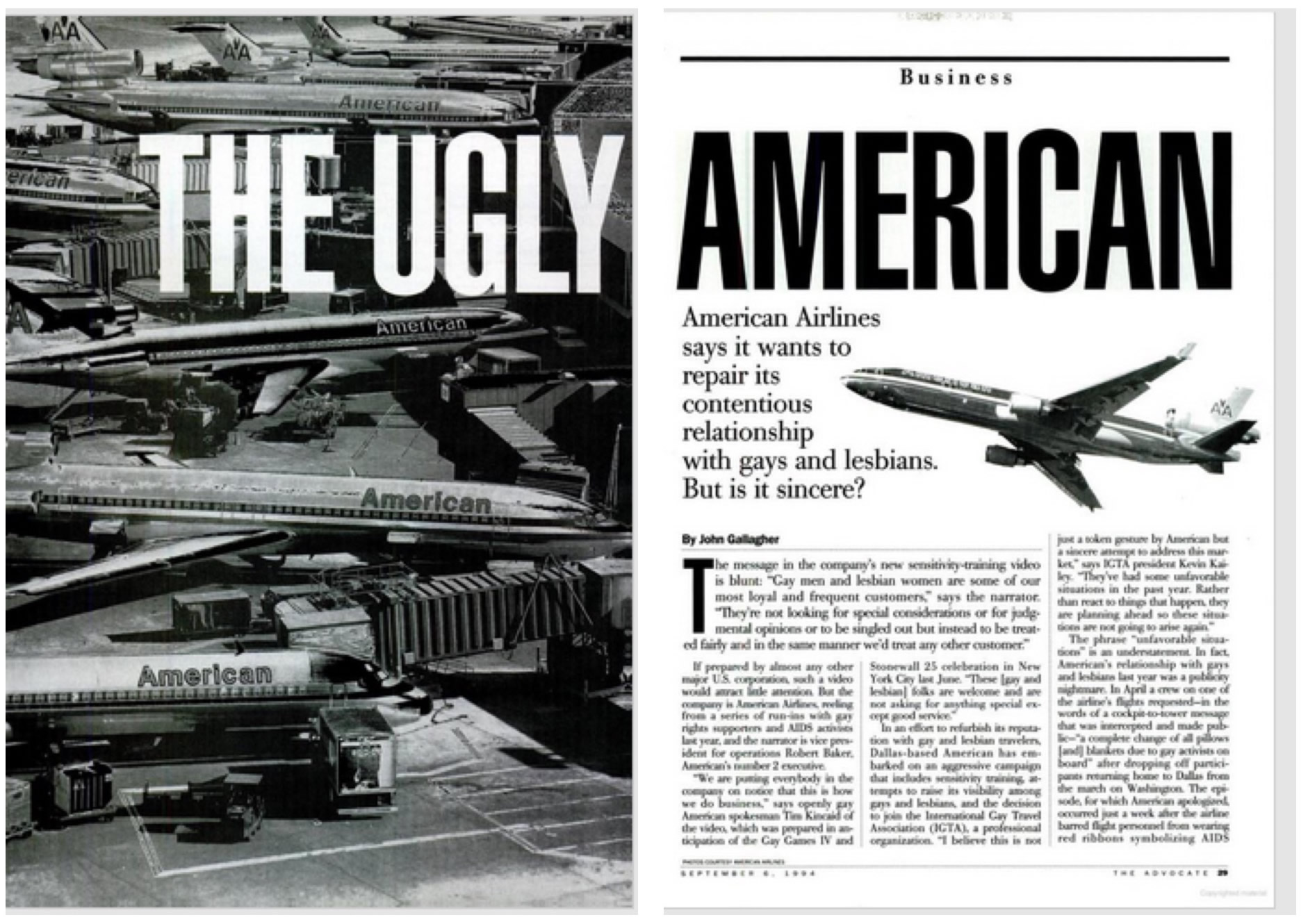

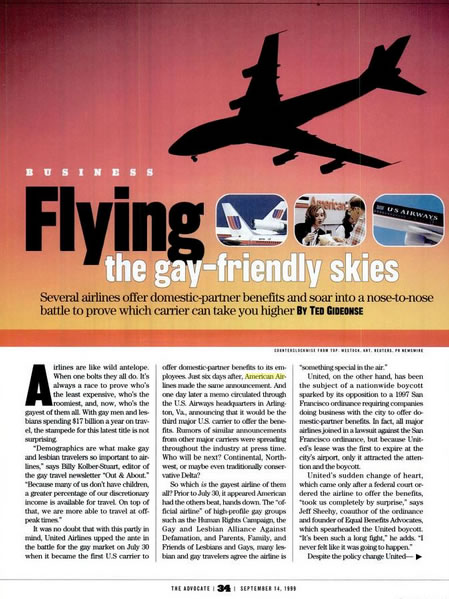

Once again, American Airlines had made the headlines. As a result of this incident (which resulted in a class-action lawsuit), LGBT activists, including AIDS activists, leaders of AIDS service organizations, workplace policy groups, and medical research organizations, protested the airline. LGBT publications called for a boycott of American Airlines (see Figure 4). This backlash garnered negative national and international publicity for the corporation.

Figure 4. An article appearing in the September 6, 1994, issue of The Advocate (pp. 28-29).Research

Research for this article is based on information from a management case study (Witeck & Kincaid, 2011a, 2011b), mainstream and LGBT media coverage of the events, and conversations with Bob Witeck, the LGBT communications consultant for American Airlines at the time of the events. Witeck has worked with AA since 1994 providing counsel on LGBT public relations, marketing, and workplace relationships. News coverage was collected through LexisNexis and Newsbank database searches and a digital and print archive of The Advocate, the leading LGBT publication in the United States. More than 100 documents were gathered and analyzed.

Strategies

LGBT publics, including activists, customers, and employees, were at the heart of the crisis response. It is important to note, however, that these groups are not mutually exclusive and there is much overlap between these activists, customers, and employees.

During this time, gay men were dying from HIV/AIDS in massive numbers and in light of this epidemic, LGBT activists were a vocal public. This public included grassroots activists, leaders, and friends and families of LGBT people. Given the silence surrounding HIV/AIDS at the time, activists used the incidents to bring light to inequalities facing LGBT people.

Historically, organizational response to activist publics varies from resistance to building cooperative relationships. Oliver (1991) identified five strategic responses organizations often employ when faced with activists: 1) acquiescence, or giving in to activists’ demands; 2) compromise, or negotiating with activists to resolve the situation; 3) avoidance, or concealing problems or establishing a barrier between the organization and activists; 4) defiance, or actively engaging opponents in debate; and 5) manipulation, or making superficial changes to an organization’s practices without substantive changes. American Airlines, however, did not employ these strategies and worked with activists and internal and external LGBT publics to address the incidents. Executives at AA realized this situation required more than a response; something was broken. American Airlines needed to identify the issues and repair underlying causes; it had to walk the walk, not just talk the talk.

LGBT customers were emerging as a demographic category and little formal market research existed about LGBT people. At the time of the incidents, relationship building with LGBT consumers was a rare occurrence, aside from a handful of beverage companies. There was no substantial research on LGBT publics and little reliable data existed about LGBT people or households, making it challenging to justify to management the investment in such efforts.

In the early 1990s, corporate climate for gays and lesbians was one of invisibility, and virtual nonexistence for bisexual and transgender individuals. At the time of the incidents, LGBT employees were overwhelmingly not out (or open about their sexuality) in the workplace, thus were an invisible minority. No federal laws and few state and local statutes existed to protect the rights of LGBT people. Most employers did not have domestic partner benefits, nor inclusive benefits policies that included same-sex partnerships. At the time, a few corporations began to offer health benefits to same-sex couples, but largely management did not recognize the importance of extending equal employment benefits to LGBT employees.

Execution

LGBT Community Relations Plan

American Airlines worked to build relationships with LGBT leaders, activists, and media. AA partnered with Witeck-Combs Communications—a consulting firm specializing in LGBT workplace issues and marketing relationships—to respond to the situation. Management recognized that in order to truly build a meaningful relationship with this community, American Airlines had to communicate honestly, transparently, and authentically as fellow LGBT individuals and LGBT professionals. During this time when many LGBT people lived in the closet, LGBT employees were invisible, however, Tim Kincaid, a new member of the corporate communications team at the time of the incident, came out to his boss, committing to help American Airlines work through the crises. Doke described feeling the “weight lifted” and being “even more ‘in the game’ to help American manage its way through the crisis” (Witeck & Kincaid, 2011b, p. 4). These incidents opened a seat at the table for LGBT people like Kincaid. Kincaid’s insights, paired with Witeck’s counsel, proved critical in helping American Airlines.

American Airlines recognized that their corporate perception was on the line. It was imperative to find out what internal and external publics thought about American Airlines at the time. American Airlines consulted with gay and lesbian organizations and AIDS organizations, asking activists how the airline should right their wrongs. After these meetings, American Airlines pledged a corporate commitment to bridging gaps with LGBT communities. They developed a strategy based on the following four points: 1) act fast to issue a corporate apology and internal investigation; 2) educate employees on HIV/AIDS; 3) develop workplace sensitivity training; and 4) commit to a long-term goal of authenticity, trust, and transparency.

LGBT Community Relations Implementation

In response to these incidents, American Airlines committed to seeing eye-to-eye with LGBT publics, communicating with LGBT communities through honesty and trust.

American Airlines supported the historic 25th anniversary of the Stonewall March and Pride celebrations in New York City, building an alliance with LGBT activists. AA recognized that thousands of people would be travelling to New York City in June 1994 for this event, so they provided funding for air travel for special guests, including LGBT leaders and speakers.

American Airlines’ Corporate Communication Department issued a formal apology from Crandall to all employees and LGBT activist groups, acknowledging wrongdoing and presenting plans for fixing the issues. The letter stated that American would be implementing a “very active program of AIDS education for employees” that they would conduct with the American Red Cross (“American Airlines Issues Statement,” 1993, para. 1). AA immediately added a corporate non-discrimination policy that included sexual orientation, making American one of the first major U.S. airlines to add sexual orientation as a protected classification. Upon revision of corporate policies, American communicated to employees about policies, education, and training.

Internally, the communication department developed a 10-minute training video for employees about the significance of Stonewall narrated by then Senior Vice President of Operations (later Vice Chairman) Bob Baker, one of the airline’s most senior leaders. Baker articulated the importance of the parade and the celebration, noting that employees who identified as LGBT would be participating. In addition to the historical information, the video communicated to employees that there would be LGBT people travelling via American Airlines who may have HIV/AIDS and deserve to be treated with respect and dignity.

Management recognized the importance of bringing attention to HIV and AIDS and reviewed and revised the corporate “no-IV” policy to permit personal IV use onboard. American Airlines partnered with HIV/AIDS organizations (including the National Association of People With AIDS, National Business Coalition on AIDS, and American Foundation for AIDS Research) to demonstrate corporate awareness, organizing teams to walk in AIDS fundraisers, and flying panels of the AIDS quilt (a memorial project celebrating the lives of those who have died from AIDS-related causes) for public display in cities around the U.S.

American empowered employees to organize the company’s first LGBT resource group (GLEAM—Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Employees at American), recognizing LGBT employees as a resource of information, helping bridge gaps both externally and internally. The C-suite recognized that the airline needed to have policies and procedures in place that established best practices.

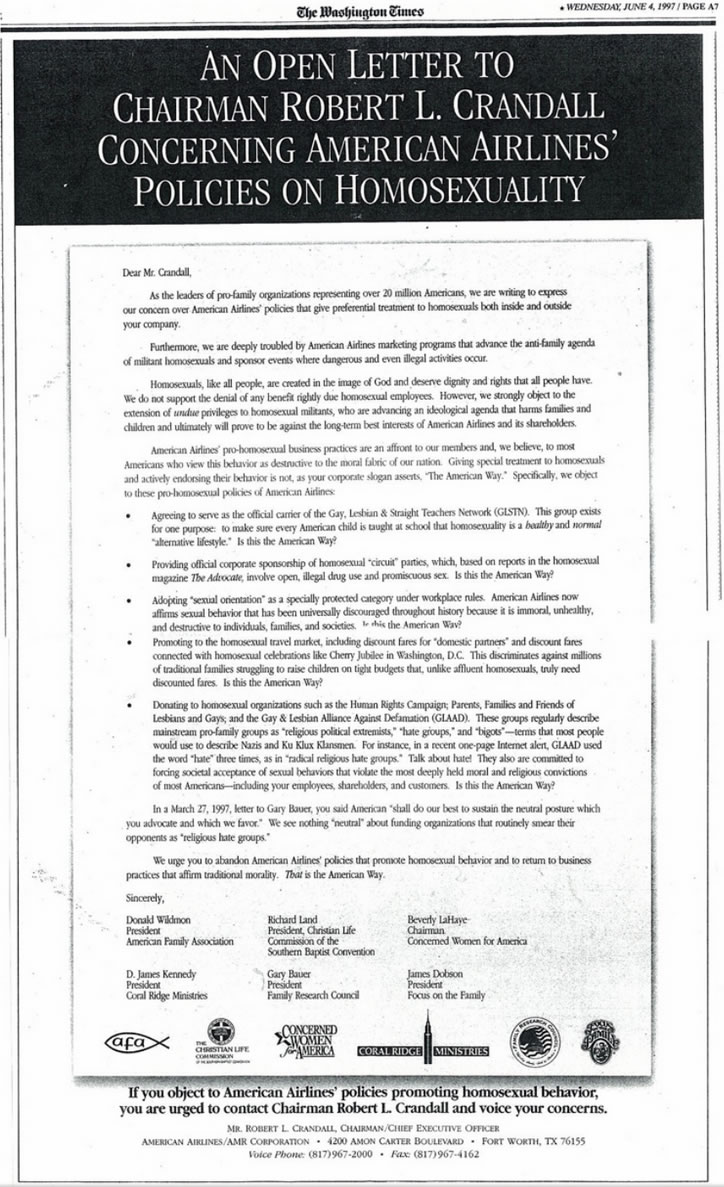

Opposition

However, not everything was rainbows; American Airlines faced pushback from conservative political activists after implementing policies aimed at inclusion and protection of LGBT publics. In conjunction with the Family Research Council, a conservative Christian group and lobbying organization, in 1997 Anita Bryant, singer and former spokeswoman for the Florida Citrus Commission, denounced AA for its “immoral” benefits program, asking, “What are you going to develop next? A pedophilia market?” (Southern Poverty Law Center, 2005, para. 62). That same year, 19 conservative and religiously affiliated organizations wrote a public letter to CEO Bob Crandall opposing corporate policies toward LGBT people. This coalition purchased ads in major U.S. newspapers, featuring parts of his letter (see Figure 5), claiming that American Airlines was promoting homosexuality. American’s management team met with members of the coalition at the AA’s headquarters in March 1998 to convince critics it was “not picking sides in any ‘culture war’” (Witeck & Kincaid, 2011b, p. 12).

Figure 5. An ad appearing in the June 4, 1997, issue of The Washington Times (p. A7).After the meeting, the Dallas Observer reported that the conservative coalition stated they had “scored a major victory at American” (as quoted in Farley, 1998, para. 6), suggesting the airline had changed its position. The Concerned Women for America, a conservative organization, issued a news release stating American Airlines would “stop promoting homosexuality” and would stop sponsoring “homosexual parties (Farley, 1998, para. 7). The press release continued:

No longer will air travelers on American Airlines fear that a portion of their fares is funding activities that may be in direct conflict with their religious beliefs. We are so pleased that American has decided to stop endorsing this deadly behavior. (as quoted in Farley, 1998, para. 8)

In response, executives at American Airlines reported feeling “set up” (Witeck & Kincaid, 2011b, p. 13). The day following the news release, American released a statement that such commitments had not been made, declaring that AA would stay nonpartisan and committed to their business objectives. Despite the letter and ad, the threat of a counter-boycott fell short and LGBT-inclusive policies and procedures remained in place, establishing the foundation for a commitment to LGBT issues and publics.

Evaluation

American Airlines pushed the envelope at a time when supporting LGBT publics was seen as financially risqué and politically problematic. AA was a pioneer in LGBT relations, developing and adopting policies and best practices for engaging with internal and external LGBT publics.

American Airlines had many corporate firsts with the LGBT community. American was the first airline to a) implement same-sex partner benefits; b) include sexual orientation and gender identity in workplace nondiscrimination policies; c) form a company-recognized LGBT employee resource group; d) endorse the Employment Non-Discrimination Act; and e) include LGBT-owned businesses in the supplier diversity program (American Airlines, n.d.).

American Airlines developed an LGBT employee group, GLEAM, something that was never done by a corporation before. In 1994, several employees formed the Rainbow TeAAm, the first gay-identified sales and marketing team, tasked with handling incoming gay travel requests and to promote American Airlines at LGBT community events. American worked to ensure consistency internally and externally by coordinating activities and strategy between the GLEAM team and the Rainbow TeAAM so that policies were consistent with marketing and public relations.

These strategies resulted in new policies and procedures that established American Airlines as an industry leader in LGBT relations. As a result of these responses and initiatives, American gained positive coverage in LGBT media and among LGBT community leaders (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. An article appearing in the September 14, 1999, issue of The Advocate (pp. 34-36).LGBT groups wanted to do business with an organization that acknowledged LGBT people through fairness.

Analysis and Discussion

Since the beginning of the LGBT movement in the U.S. in the mid-20th century there have been several instances of corporate and activist engagement. The American Airlines case is a game-changing example of how an organization identified wrongdoings, responded quickly, revised policies, educated employees, and actively worked with LGBT publics to develop relationships. American Airlines has stayed devoted to LGBT publics and more than 20 years later remains a community partner dedicated to diversity initiatives.

This case study raises important questions regarding responding to a crisis, responding to activists, and building relations with marginalized publics. The American Airlines incidents provide a historical lens into public relations and crisis communication. As demonstrated in the case study, the pillows and blankets and IV incidents were “focusing events” (Kingdon, 1984), that established an emotional impetus to bring about organizational policy change. Both episodes were moments that accentuated social and political attention around corporate interaction with LGBT people and issues. Focusing events, like these incidents, often call attention to an issue and bring to light less visible stakeholders and marginalized perspectives.

Public relations can provide an “ethical role” to organizations by ensuring “disparate voices” both internal and external to the organization are heard (Coombs & Holladay, 2007, pp. 46-47). This case study demonstrates the need to have an understanding of crisis communication that is inclusive of the perspectives of marginalized publics that are often most impacted by the crisis. Rather than understanding the crisis from a purely corporate perspective, American Airlines included the interpretations, practices, and communicative strategies of LGBT publics, an often-silenced voice during this era. Unlike many organizations that take a top-down approach to crisis management, AA turned to LGBT publics for insights in how to respond. By engaging LGBT communities in participatory ways rather than imposing a corporate crisis resolution, American Airlines empowered activists to help develop solutions.

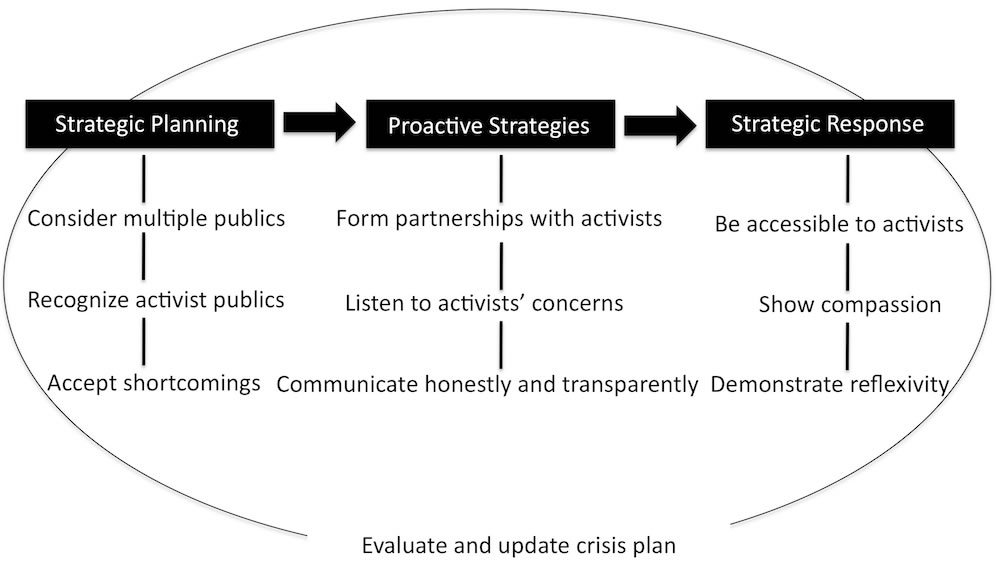

Borrowing from Seeger’s (2006) model of best practices in risk and crisis communication, this article puts forth a conceptual model of crisis communication and activist relations for public relations practitioners. The model (see Figure 7) identifies three stages in crisis communication and activist relations: 1) strategic planning, 2) proactive strategies, and 3) strategic response. The model begins with recognition of multiple publics, including activists, that may bring to light issues and concerns with organizational practices or policies. The second stage encompasses strategies for working with activists to identify concerns and build relationships through open and honest communication. Lastly, a strategic response includes accessibility to activists and compassionate and reflexive engagement. This model is cyclical, denoting these stages of crisis communication are in flux and activist relations is always a process in need of evaluating and updating.

Figure 7. Crisis communication and activist relations.As a result of engagement with LGBT activists, customers, and employees, American Airlines came out in support of LGBT publics, illustrating how public relations professionals can function as change agents. When an organization supports a cause through policy change or sponsorship, it signals to employees and customers that the organization is really committed to these changes and to these issues. In a 1998 interview, Robbin Burr, the head of American’s gay marketing team and co-chairwoman of GLEAM, noted: “Good sales and marketing [are] based on good relationships, and we have good relationships with the organizations and associations [we have] worked with over the past few years” (Gideonse, 1999, p. 34).

Fast-forward 20 years. American Airlines remains a pioneer in LGBT relations. In June 2015, after the Supreme Court decision to legalize same-sex marriage, American Airlines’ Chairman and CEO Doug Parker publicly noted: “This is a historic moment for our country and for many of American’s employees. Today’s decision reaffirms the commitment of companies like American that recognize equality is good for business and society as a whole” (American Airlines, 2015). That same month in celebration of LGBT pride, AA temporarily changed its Twitter avatar to a rainbow flag logo. Opponents criticized the airline, but American’s social media team stood firm defending their position (see Figure 8). Despite opposition, American Airlines continues to be an industry leader in their commitment to LGBT issues and stakeholders.

Figure 8. American Airlines’ Twitter conversation with a disgruntled user on June 15, 2015.This case study demonstrated how American Airlines responded to, worked with, and evolved through its interaction with activists. Since 2002, American Airlines has received the highest score for the Human Rights Campaign’s (HRC) Corporate Equality Index, which ranks organizations in the U.S. on inclusion of LGBT employees. American is the first and only airline (and one of nine organizations) to earn a perfect score every year, earning HRC’s title of “Best Places to Work for LGBT Equality” (Human Rights Campaign, 2015), demonstrating its commitment to diversity and equity.

Although same-sex marriage is now legal in the U.S., issues still exist for LGBT equity. As of September 2015, in 31 states it is still legal to discriminate based on sexual orientation and gender identity in employment, housing, business, and education. Contemporary issues impacting LGBT people and communities include non-discrimination laws, transgender rights, LGBT parenting laws, and legislation that protects LGBT youth, often the most marginalized members of the LGBT community. As these areas demonstrate, LGBT people and issues are complex and diverse. Moving forward, strategic communication practitioners must account for the multidimensional nature of LGBT identity, including the intersection with demographic categories (gender, race, ethnicity, economic class, ability) as well as contextual factors, including social, economic, geographic, political, technological, communicative, and commercial considerations.

The Commercial Closet Association (2008), an advocacy organization whose work focuses on representations of LGBT issues and people, has developed guidelines for advertising professionals. Drawing from these guidelines, this article concludes with a list for public relations practitioners engaging with both internal and external LGBT publics:

- Understand public opinion toward LGBT issues.

- Recognize LGBT people are already your customers and employees.

- Make sure internal and external policies and procedures regarding sexual orientation and gender identity are consistent.

- Don’t teeter on policies and procedures regarding sexual orientation. Be consistent.

- Be sure to consider gender identity as part of corporate policies and procedures.

- Don’t pigeonhole LGBT employees as the voice of all LGBT issues. Seek input from other resources or conduct your own primary research.

- Make a seat at the table for LGBT employees.

- Best practices of LGBT inclusion occur at every level of the corporate hierarchy.

- When creating content avoid using cliché and stereotypes that might perpetuate homophobia and transphobia.

- Don’t employ LGBT stereotypes in content to elicit humor, shock, or arousal.

- Include real, openly LGBT celebrities, athletes, and everyday people in strategic communication content.

- Continue to seek and do research on LGBT publics including demographics, psychographics, and media habits.

- Consider sponsorship with LGBT organizations to demonstrate commitment to equality and diversity.

Activities and Discussion Questions

- Consider what may have happened if American Airlines did not respond as they did in 1994. What are other ways American Airlines could have responded and what might that have resulted in?

- Imagine yourself as various stakeholders in this case: 1) an LGBT employee at American Airlines in 1993; 2) an LGBT activist; 3) an LGBT consumer; and 4) a political conservative. Consider some of the main issues you face. What are the concerns you want addressed? How do you want American Airlines to respond? What sort of strategies might you employ to make sure American Airlines hears your perspective?

- What are the implications of taking a side on a social issue? What are the implications of not taking a side on a social issue? What considerations should decision makers and communicators take into account?

- If you were the spokesperson for American Airlines, how would you respond? What would you do to prepare for a news conference? Conduct a mock press conference:

- Understanding the community’s concerns?

- Engaging local media in distributing useful information?

- Explaining complex scientific and technical information to residents?

- Coordinating communication with other government departments and agencies and the fire authority?

- Assume you are the communications officer for American Airlines. If the two incidents described above happened today, what elements of the communication approach would need to change? How might social media change the response? What challenges might digital journalism present?

- Although LGBT acceptance continues to grow at an accelerated pace in recent years, it remains a potentially polarizing issue. How may a practitioner’s individual ethics or beliefs play out in carrying out communication with LGBT publics? Imagine you are a new communication professional. How might you respond if asked to help roll out a company policy or crisis plan that runs in opposition to your personal beliefs?

Note

[1] While the term gay liberation is used to mark this historical era, it was often encompassing of lesbian, bisexual, and transgender/transsexual communities.

References

American Airlines. (n.d.). LGBT equality in the workplace: Perfect rating in the Corporate Equality Index every year from the start. American Airlines. Retrieved September 15, 2015, from http://www.aa.com/i18n/urls/equality.jsp?anchorLocation=DirectURL&title=equality

American Airlines. (2015). American is a proud supporter of the LGBT community. American Airlines Diversity & Inclusion. Retrieved August 3, 2016, from http://hub.aa.com/en/dv/pride-month

American Airlines issues statement on Flight 701 incident. (1993, April 29). PR Newswire.

Carter, D. (2009). What made Stonewall different. The Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide, 16(4), 11-13.

Commercial Closet Association. (2008, March). Commercial Closet Association best practices: Building GLBT awareness and inclusion in mass/business-to-business advertising. Retrieved August 3, 2016, from http://www.adrespect.org/common/news/reports/detail.cfm?Classification=report&QID=4141&clientID=11064&topicID=0&subnav=resources&subsection=resources

Coombs, W. T. (1999). Information and compassion in crisis responses: A test of their effects. Journal of Public Relations Research, 11, 125-142.

Coombs, W. T., & Holladay, S. J. (2001). An extended examination of the crisis situation: A fusion of the relational management and symbolic approaches. Journal of Public Relations Research, 13, 321-340.

Coombs, W. T., & Holladay, S. J. (2007). The negative communication dynamic. Exploring the impact of stakeholder affect on behavioral intentions. Journal of Communication Management, 11(4), 300-312.

Crable, R. E., & Vibbert, S. L. (1985). Managing issues and influencing public policy. Public Relations Review, 11(2), 3-16.

den Hond, F., & de Bakker, F. (2007.) Ideologically motivated activism: How activist groups influence corporate social change activities. Academy of Management Review, 32, 901-924.

Dougall, E. K. (2006). Tracking organization–public relationships over time: A framework for longitudinal research. Public Relations Review, 32(2), 174-176.

Duberman, M. B. (1993). Stonewall. New York: Penguin Group.

Fairbank, K. (1993, April 29). Airline apologizes for linen-change request made after gay group flies. AP News Archive. Retrieved August 3, 2016, from http://www.apnewsarchive.com/1993/Airline-Apologizes-for-Linen-change-Request-Made-After-Gay-Group-Flies/id-aa34cd982aa9402cb6cb71419c5e4b49

Farley, R. (1998, April 16). Straighten up and fly right. Dallas Observer. Retrieved August 3, 2016, from http://www.dallasobserver.com/news/straighten-up-and-fly-right-6397936

Fearn-Banks, K. (2001). Crisis communication: A review of some best practices. In R. L. Heath (Ed.), Handbook of public relations (pp. 479-485). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Gallagher, J. (1993, December 28). Flight risk. The Advocate, p. 31.

Gideonse, T. (1999, September 14). Flying the gay-friendly skies. The Advocate, p. 34.

Heath, R. L. (1997). Strategic issues management: Organizations and public policy challenges. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Human Rights Campaign. (2015). Corporate Equality Index. Human Rights Campaign. Retrieved August 3, 2016, from http://www.hrc.org/campaigns/corporate-equality-index

Kingdon, J., (1984). Agenda, alternatives, and public policies. Boston, MA: Little Brown.

LaFrank, K. (1999, January). National historic landmark nomination: Stonewall. U.S. Department of the Interior: National Park Service.

Milestones in the American gay rights movement. (n.d.). American Experience. Retrieved August 3, 2016, from http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/timeline/stonewall

Morris, B. J. (2015). History of lesbian, gay, & bisexual social movements. American Psychological Association. Retrieved August 3, 2016, from http://www.apa.org/pi/lgbt/resources/history.aspx

Oliver, C. (1991). Strategic response to institutional processes. Academy of Management Review, 16, 145-179.

Rimmerman, C. A. (2002). From identity to politics: The lesbian and gay movements in the United States. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Rochon, T. R. (1988). Between society and state: Mobilizing for peace in Western Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Rowley, T. J., & Moldoveanu, M. (2003). When will stakeholder groups act? An interest- and identity-based model of stakeholder group mobilization. Academy of Management Review, 28, 204-219.

Seeger, M. W. (2006). Best practices in crisis communication: An expert panel process. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 34(3), 232-244.

Seeger, M. W., Sellnow, T. L., & Ulmer, R. R. (2001). Public relations and crisis communication: Organizing and chaos. In R. L. Heath (Ed.), Handbook of public relations (pp. 155-166). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Smith, M. F. (1997, November). Public relations from the “bottom-up”: Toward a more inclusive view of public relations. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the National Communication Association, Chicago, IL.

Smith, M. F. (2005). Activism. In R. L. Heath (Ed.), Encyclopedia of public relations (pp. 5-9). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Smith, M. F., & Ferguson, D. P. (2001). Activism. In R. Heath (Ed.), Handbook of public relations (pp. 291-300). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Southern Poverty Law Center. (2005, April 28). A dozen major groups help drive the religious right’s anti-gay crusade. Retrieved August 3, 2016, from https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/intelligence-report/2005/dozen-major-groups-help-drive-religious-right’s-anti-gay-crusade

Ulmer, R. R., Sellnow, T. L., & Seeger, M. W. (2007). Effective crisis communication: Moving from crisis to opportunity. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Witeck, B. & Kincaid, T. (2011a). Navigating through a perfect storm: American Airlines and the LGBT Community: Part A. 2011 Reaching OUT LGBT MBA Conference case competition. Los Angeles, CA: Reaching OUT MBA.

Witeck, B. & Kincaid, T. (2011b). Navigating through a perfect storm: American Airlines and the LGBT Community: Part B. 2011 Reaching OUT LGBT MBA Conference case competition. Los Angeles, CA: Reaching OUT MBA.

Wrigley, B. J., Salmon, C. T., & Park, H. S. (2003). Crisis management planning and the threat of bioterrorism. Public Relations Review, 29(3), 281-290.

Vibbert, S. L. (1987, May). Corporate discourse and issue management. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Communication Association, Montreal, ON.

ERICA CISZEK, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of integrated strategic communication in the Jack J. Valenti School of Communication at the University of Houston. Her research focuses on the intersections of identity, communication, and technology and how organizations communicate with marginalized and minority populations. Email: elciszek[at]central.uh.edu.

Editorial history

Received September 6, 2015

Revised December 14, 2015

Accepted December 14, 2015

Published August 3, 2016

Handled by guest editor N. T. J. Tindall; no conflicts of interest